At the start of the Great War in 1914, only about half of the 300,000 Native Americans in the United States were citizens. Although the Fourteenth Amendment granted citizenship to all “persons born or naturalized in the United States,” it did not apply to Native Americans because they fell under the jurisdiction of tribal authorities rather than the U.S. government.

Congress provided a pathway to Indigenous citizenship through the allotment system that started with the controversial Dawes Act of 1887. Under this law, Natives who surrendered their communal rights to tribal property received a plot of land to farm or graze and gained recognition as citizens. The government opened any leftover reservation land to settlement and development by non-natives. Many Native Americans refused to go along with the allotment system, retaining their non-citizen status and resisting the pressure to assimilate. Nonetheless, tribal landholdings still plummeted by over 80 million acres in the decades after the Dawes Act went into effect.

The United States’ entry into the war in 1917 attached new importance to the issue of Native citizenship. Shortly after declaring war on Germany, Congress established a national draft, directing all males between the age of 21 and 30 to register for military service. Non-citizens were exempt from conscription but still required to register with the federal government. Members of a few tribes, such as the Navajo and Ute, protested this provision, seeing it as an infringement of their rights as a sovereign people. On a handful of occasions, Indian opposition to the draft law flared up into threats of or actual violence.

The majority of Native communities, however, rallied behind the war effort. The Onondaga and Oneida Nations went so far as to issue their own declarations of war against Germany, an act that demonstrated not just loyalty to the American cause but also their tribal autonomy. All told, some 6,000 Native Americans volunteered for service. Another 6,500 were drafted, including non-citizens who waived their right to exemption. Notably, only one percent of Indian men who registered for the draft claimed deferments, a rate that was far lower than that of the general population.

Patriotism motivated many Indian recruits, but so did a desire to continue the warrior traditions of their tribe and gain respect and prestige. Tribes held honoring ceremonies to send off the newly enlisted and welcome home those returning from the war.

In contrast to previous conflicts when they were used primarily as scouts or auxiliaries, Native Americans were fully integrated into all branches of the military. They served as sailors and marines, engineers and aviators, doctors and ambulance drivers, and artillerymen and foot soldiers. Indians assigned to front-line infantry units were among the first combat troops to reach France and they saw extensive action on the Western Front during the decisive Allied offensives of 1918.

Cultural stereotypes of Indian males as natural and gifted fighters led commanders to assign Native soldiers the more dangerous duties, employing them as snipers or sending them on scouting mission behind enemy lines. Soldiers from the Cherokee, Choctaw, and several other tribes also rendered invaluable service as code talkers. They transmitted military communications by field telephone in their Native tongues to prevent the Germans from deciphering intercepted messages.

Native American soldiers repeatedly proved their bravery on the battlefield and many went home highly decorated. But their valor came at a high cost: about five percent were killed in action, a rate five times greater than that of American forces overall. Their contributions did not go unrecognized. After the war, Native Veterans became eligible for the same benefits as non-natives, but Congress also conferred on them another reward: eligibility for citizenship. The wording of the 1919 law offering citizenship to any honorably discharged Native American who chose to apply for it was significant, as the statute explicitly stated that their rights to tribal property would not be affected.

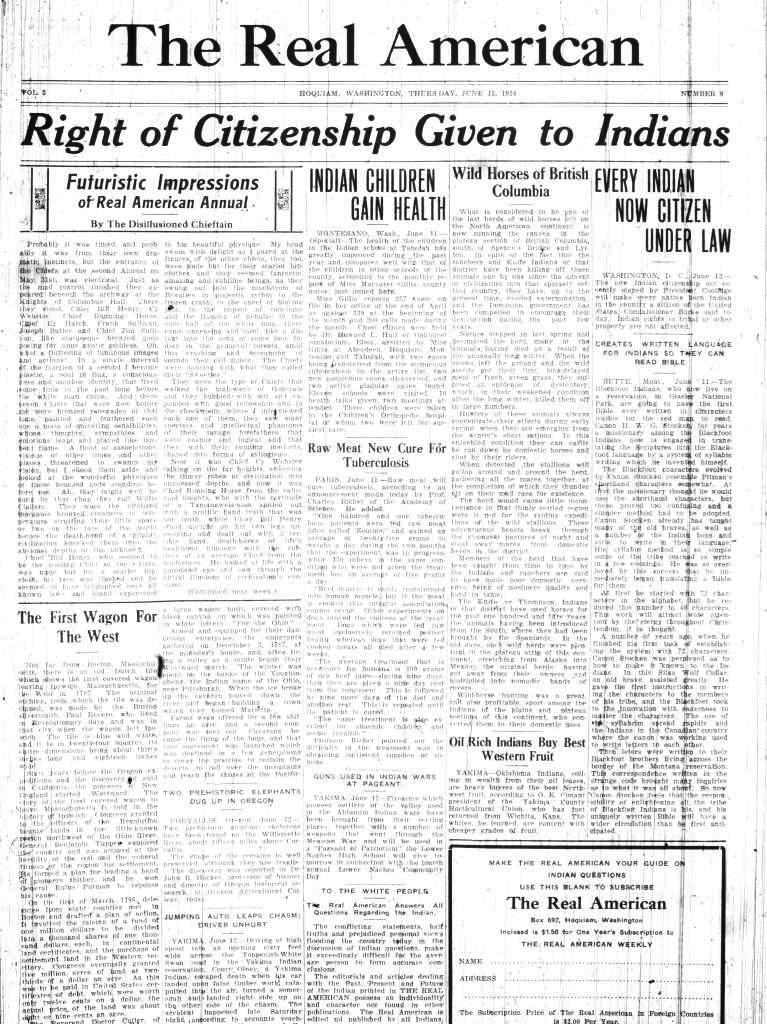

Five years later, Congress used the same language in the Indian Citizenship Act, which unilaterally granted citizenship to all Indigenous Americans born in the United States. Passage of this landmark law represented a major victory for Indian interests, as Native citizenship was no longer contingent on the relinquishment of claims to tribal lands.

Not all Natives welcomed the change in status. Some saw it as a blow to tribal identity and autonomy. Universal citizenship also did not bring about the end of legal and popular discrimination against Native Americans nor did it prevent state and local governments from curtailing Indian voting rights in much the same way that they denied African Americans access to the ballot. These issues notwithstanding, Indian soldiers through their service in the Great War staked a claim to citizenship without conditions and set the stage for further gains in the political stature of Native Americans afterwards.

By Scott Hudson

Virtual Student Federal Service Intern, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 93: Occupational Therapy Floor Loom

During World War I and afterwards, the United States committed to rehabilitating sick and wounded soldiers so they could resume productive lives in the civilian workforce. The emerging field of occupational therapy played a crucial role in the rehabilitative process.