On July 11, 1998, a casket containing the remains of 1st Lt. Michael J. Blassie was interred in Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery in his hometown of St. Louis, Missouri. Blassie’s journey home took 26 years. Over that span he rested in Vietnamese jungles, forensic labs, and for fourteen years, as the Vietnam War Unknown in the nation’s most revered crypt—the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery.

Enemy fire ripped through Blassie’s A-37 Dragonfly on his 132nd combat mission on May 11, 1972. His plane went into an inverted nosedive and exploded on impact in the jungles of An Loc near the Cambodian border. A recovery mission was immediately launched to secure the remains of the 24-year-old Air Force Academy graduate, but efforts were aborted due to heavy enemy presence. Blassie’s parents were notified that their son was killed-in-action and his body unrecovered.

Unbeknownst to them, a South Vietnamese soldier found the crash site months later, along with Blassie’s bones, his ID card, wallet, and other personal effects. The remains and possessions were sent to Saigon and labeled “believed to be” Lieutenant Blassie. In 1976 they were transferred to the Army’s Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii. Two years later, his remains were analyzed with methods subsequently found to be questionable. The results came back with a height, age, and blood type different than Blassie’s, leading the Army to designate the remains “X-26.”

Blassie’s family still believed him to be missing in action when the Defense Department in 1984 selected X-26 for interment in the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery. President Richard M. Nixon had first called for a Vietnam unknown to be laid to rest alongside the unknowns from the two world wars and Korea in 1971.

At the time of those earlier conflicts, there had been no shortage of candidates for burial because of the military’s limited ability to identify battlefield remains. Vietnam, however, posed a challenge due to advances in technology and forensic science. When the Paris Peace Accords in 1973 ended the U.S. involvement in the war, the military lacked a viable unknown to entomb at Arlington. As a result, Nixon’s directive went unfulfilled for more than a decade.

In 1978, President Jimmy E. Carter dedicated a bronze plaque at Arlington’s Memorial Amphitheater to honor those who served in the Vietnam War. Veterans groups, however, clamored for greater recognition. The political pressure increased after the unveiling of the somber Vietnam Veterans Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, DC, four years later.

In 1984, President Ronald W. Reagan decided to act. Eager to pay tribute to Veterans of the conflict in a way that would promote national healing, Reagan ordered the Defense Department to procure a Vietnam unknown to be buried in a state funeral at Arlington. Only four sets of remains existed, all of which might be identified at some future date. Despite their awareness of this possibility, officials in Hawaii on May 17, 1984, picked X-26 and had the remains casketed along with physical evidence from the crash site that should have been destroyed.

The casket was flown on a C-141B Starlifter to Andrews Air Force Base, Maryland, and then placed on display at the U.S. Capitol Rotunda, for several days to permit visitors to pay their respects. On May 28, 1984—Memorial Day—President Reagan delivered a short speech in an interment ceremony at the Tomb, eulogizing the men who had gone missing in action during the Vietnam War.

Blassie rested in anonymity at the Tomb for a decade until investigative journalists concluded that he was he was likely the unknown soldier buried in the Vietnam crypt. A 1998 CBS expose on the case featuring the Blassie family intensified demands to examine the remains with new forensic techniques. On May 14, 1998, officials opened the venerated crypt and removed the casket with X-26 for analysis. The testing positively identified Blassie and, per his family’s wishes, his remains were sent home for burial in a gravesite bearing his name.

VA serves as steward of a national cemetery system containing more than 150,000 unknowns, the vast majority from the Civil War. The identification of Blassie’s remains and his interment in VA’s Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery brought closure to one family and offers a measure of hope to other families still waiting on the recovery of their loved ones. The Vietnam crypt now sits empty and has been turned into a memorial honoring all U.S. service members recorded as missing in the Vietnam War.

By Richard Hulver, Ph.D.

Historian, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

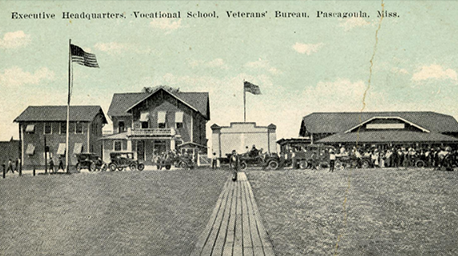

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.