NCA’s collection exhibits vintage patriotism

Memorial Day was among the most popular American holidays that, a little more than a century ago, was celebrated with abundant, affordable, and colorful penny greeting postcards. At the very time postcards exploded into a national craze, “Decoration Day” was being eclipsed by “Memorial Day” as the name of the holiday at the end of May when the nation honors its deceased service members – so these names were interchangeable. “Before the telephone, radio, television, and computer, the postcard was the chief means of communication,” said one deltiologist (someone who collects postcards) in the 1980s.1 Technology has evolved again, so Instagram may be the best comparison now.

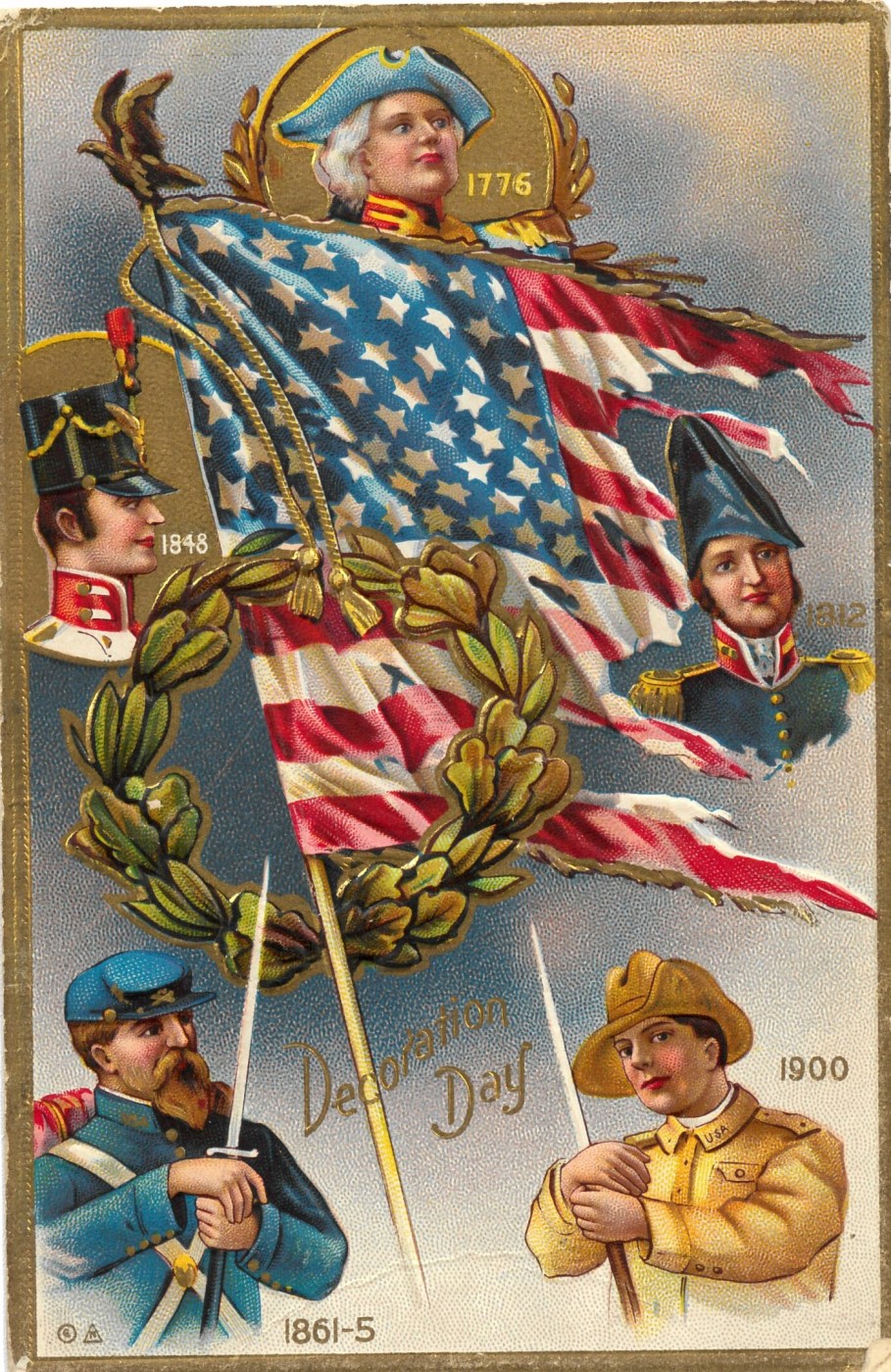

“Whatever good or ill there may be in the picture post card craze,” lauded the Journal of Education in 1910, “there are unlimited possibilities of good in them educationally.”2 Education and research motivated the National Cemetery Administration’s (NCA) History Program to acquire relevant postcards, most published between 1906 and 1913. For NCA, this ephemera falls into two categories: 1. “real photo” and edited views of national cemeteries that had matured in forty or so years, and 2. patriotic Memorial Day greetings of artist-rendered tableaus bursting with iconic American flags, eagles, and depictions of Veterans or those remembering them.

Interesting, the world’s first official postal correspondence card was issued by Austria in 1869 to provide a cheap way for soldiers to write home during the Franco-Russian War (1870-1871) and other countries quickly followed. The first collectible U.S. postcards were produced for the 1892-1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Large and small publishers, printers, artists, and local stores generated postcards, which are a little more than 3” x 5.” Fancy greeting postcards are embossed, stamped so images stand out in relief, or the designs were printed with “gold” highlights.

While the output of prolific publishers like Raphael Tuck & Sons Art Publishers to Their Majesties the King and Queen are well documented, many sources are not.3 Most cards were printed in Germany until 1909, when foreign tariffs forced a diminishing supply to the United States. After U.S. entry to World War I in 1917, reduced access to raw materials further curtailed postcard production.

What’s important, the picture or the message?

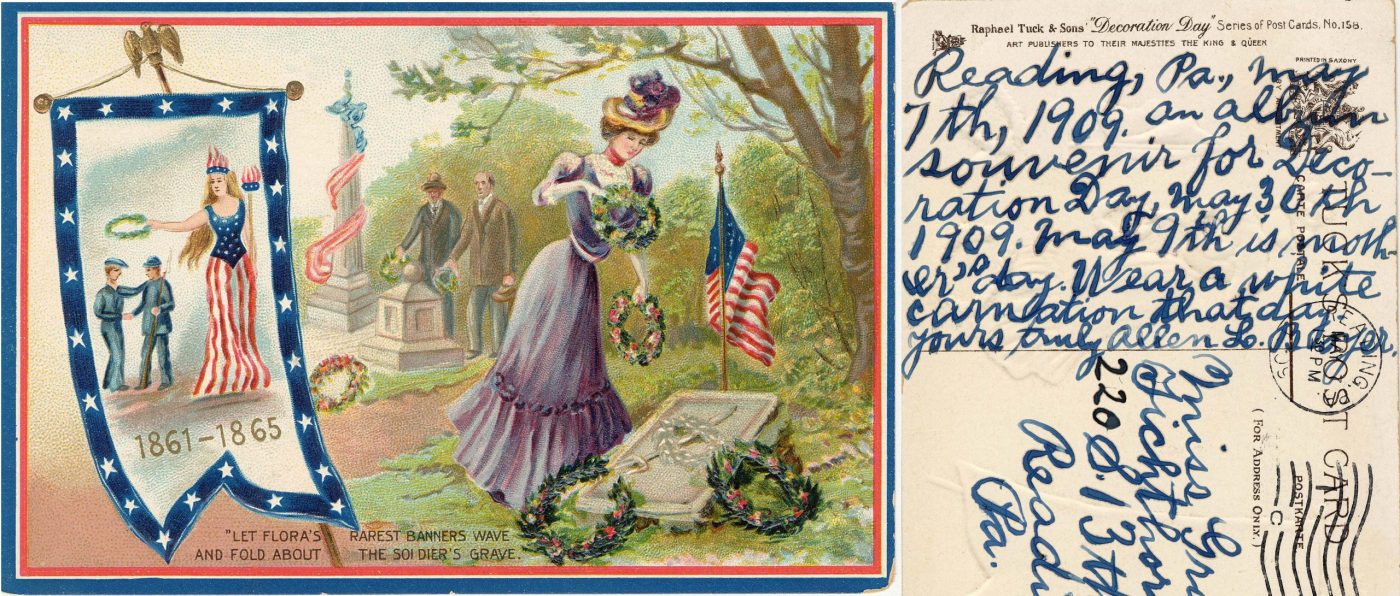

Based on NCA’s collection of 200 or so postcards, the image on the front is more valuable than the message on the back; many were likely purchased and saved as a personal collection, never meant to be mailed. Two cards postmarked May 30, 1909, were both: one sender rhetorically asks, “Do you like this one?,” and the other describes the Tuck postcard “an album souvenir for Decoration Day.”

Among the rarest collectible postcard for NCA would be photograph-based scenes of Memorial Day programs at national cemeteries that show participants, programs, and the property’s appearance. An excellent example, 1910, shows Barrancas National Cemetery in Pensacola, Florida, where troops are in formation, visitors carry umbrellas to shield themselves from the sun, and an artist-enhanced rifle salute mingles with the American flag. Whereas a routine postcard view of Grafton National Cemetery in West Virginia – where the city’s legendary Memorial Day parades conclude – is about the message. “This is w[h]ere we spent a very pleasant time on Memorial day,” Mary wrote on the unsent card, “The parades were fine. The old soldiers very enthusiastic. The flowers beautiful. The day Ideal.”

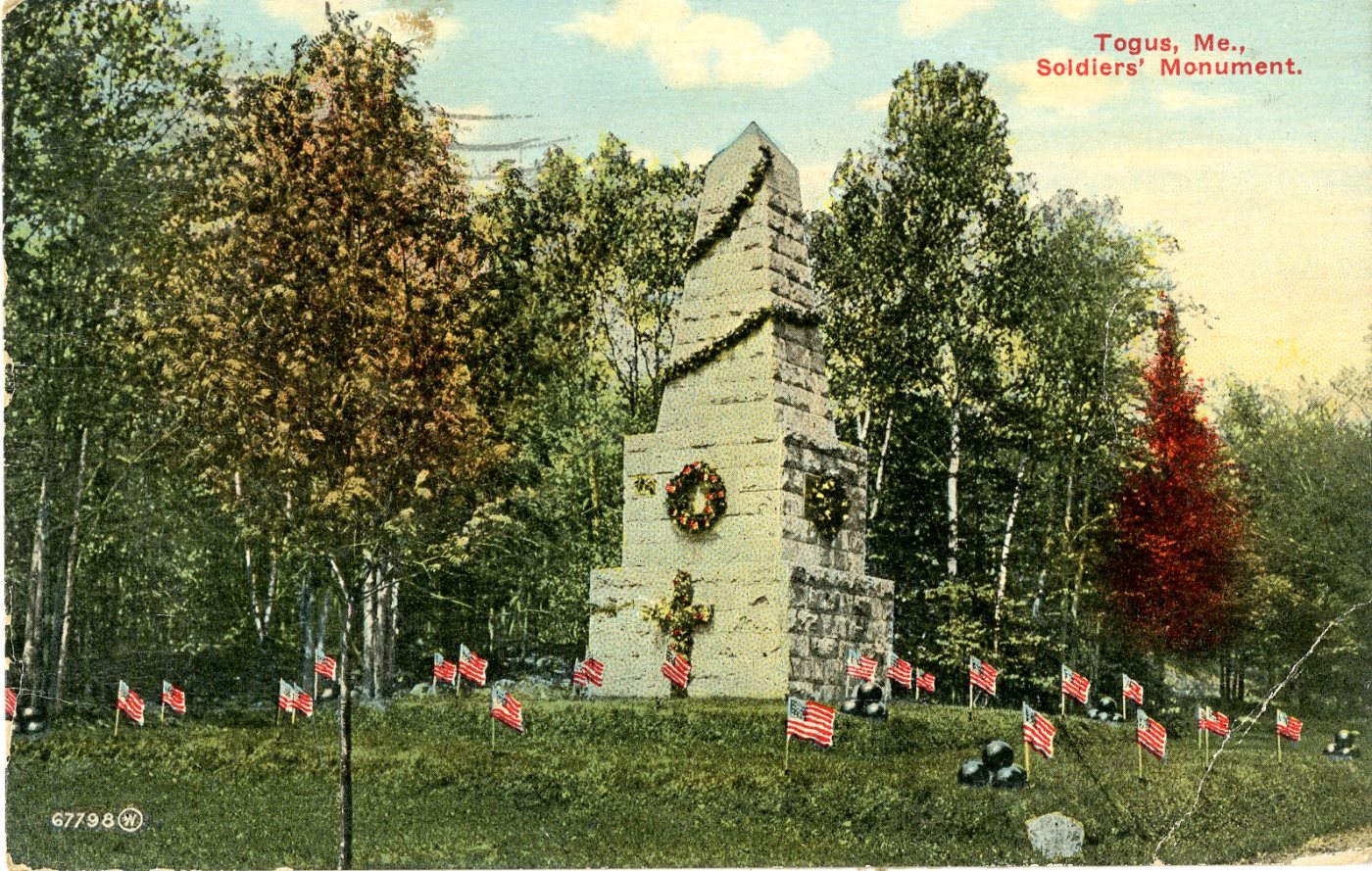

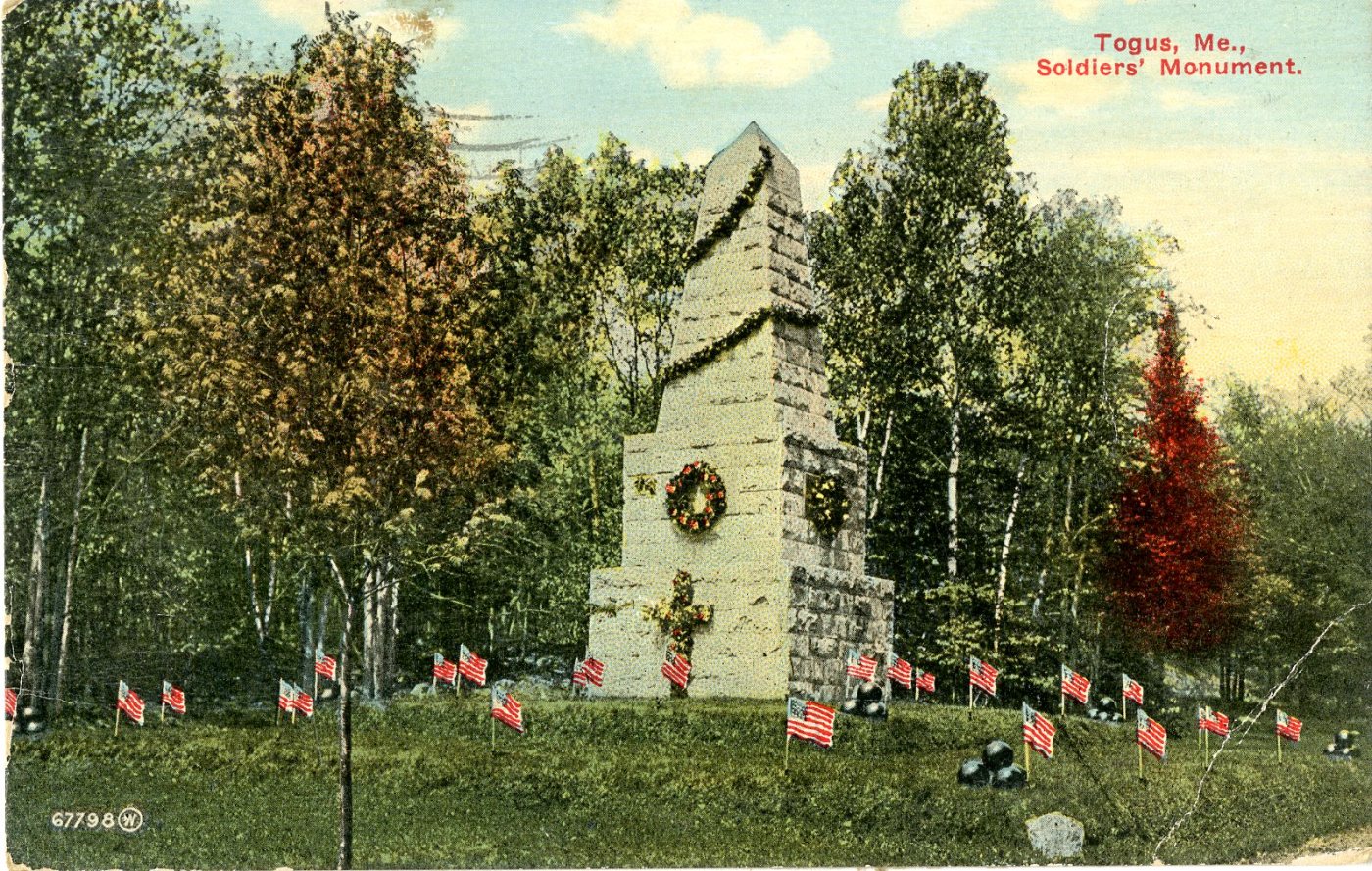

A postcard of Togus National Cemetery in Maine, mailed 1913, shows the grounds decorated with small grave flags and the Soldiers Monument draped with garlands and wreaths – all consistent with Memorial Day preparations. Togus was the Eastern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers and the campuses were popular for Veterans and tourists alike. A souvenir photo booklet of the Togus home issued by the Maine Farmer Publishing Co. in 1909, and probably available for purchase there, contains the same postcard view.

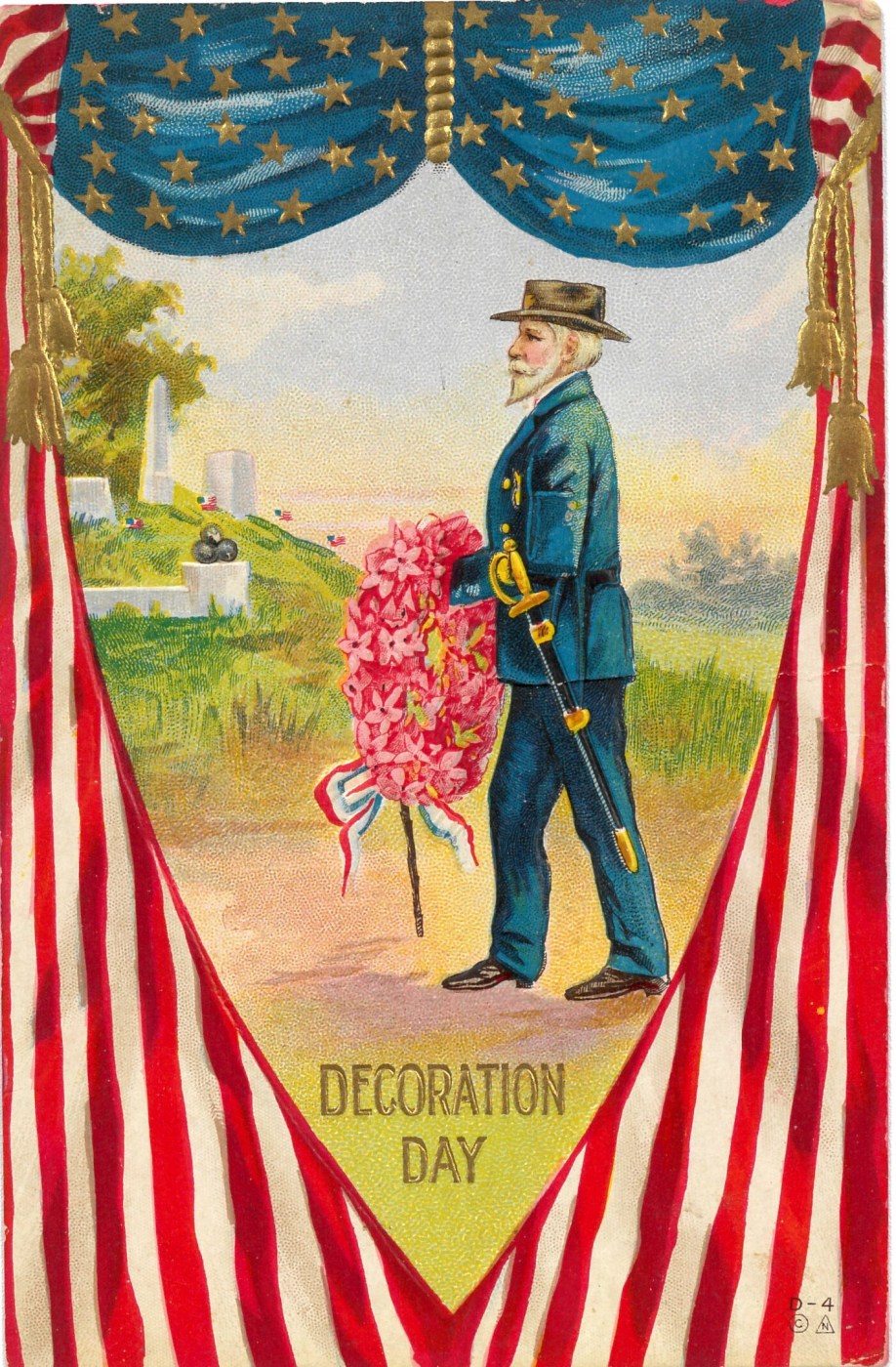

In greeting postcard parlance, Decoration or Memorial Day is part of a larger “patriotic” theme. The Civil War Veteran population was aging when the postcard frenzy took off, and that is how artists depicted them – stooped, white haired, occasionally missing an arm. One postcard cataloger describes the common “use of old Veterans, very tired and worn, never really a part of the present, but always seeking out and living in the past.”4 British publisher Raphael Tuck alone issued fifty-five different designs for the U.S. market, including two series of twelve cards each, that exude all manner of flags and bunting, flowers and laurel wreaths, and crafted scenes with layouts embellished with gold highlights or red, white, and blue borders.

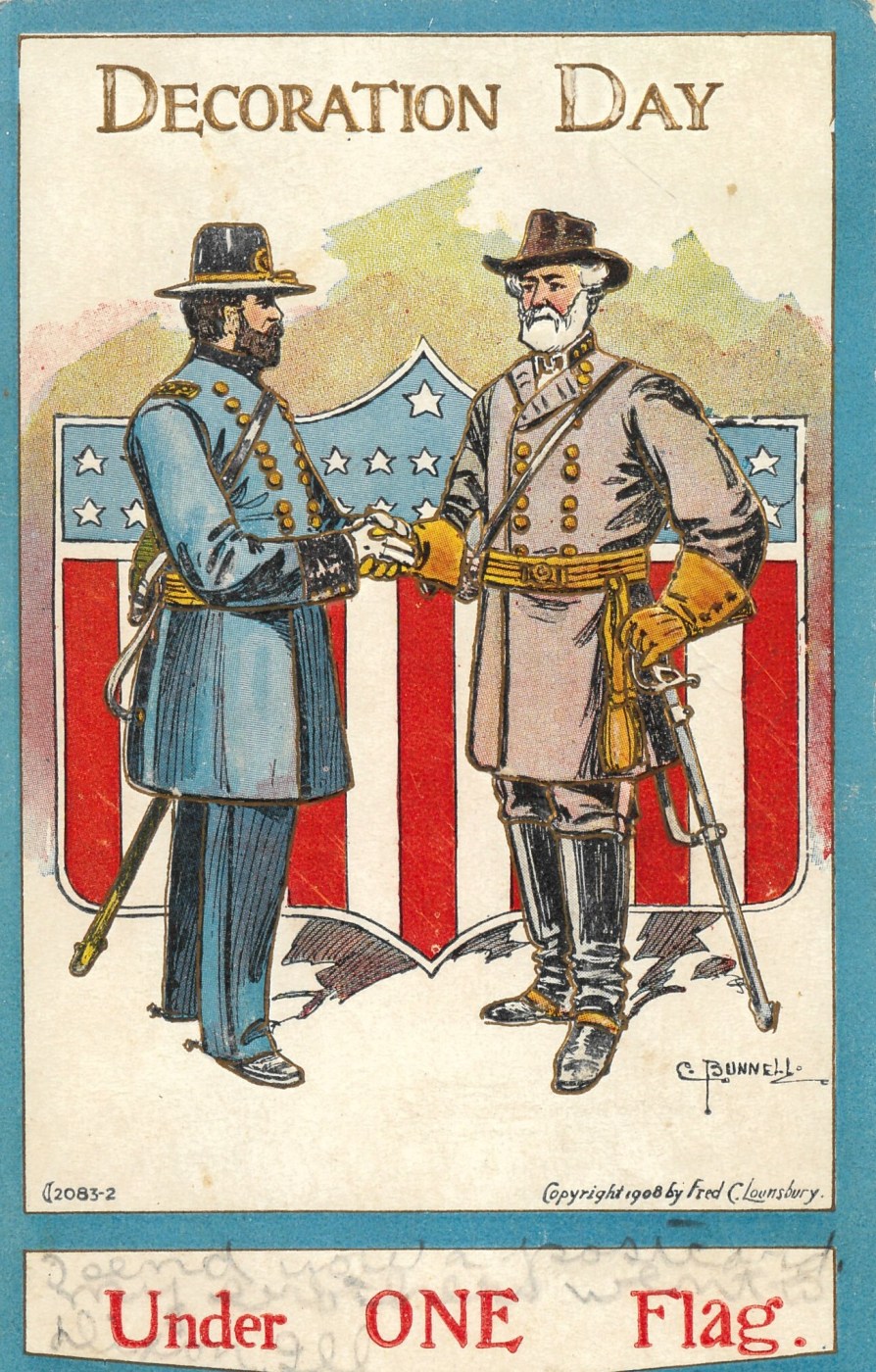

Within the Memorial Day category, designs appear to target different buyers, but most focus on the Civil War. Some are simple drawings and others are layered scenes that incorporate graves in a cemetery. Fragments of verse by nineteenth- and early-twentieth century poets such as Theodore O’Hara, Francis De Haes Janvier, Margaret E. Sangster, and U.S. Navy Commander C. P. Rees appears on many cards. Artist C. Bunnell created a more pointed message with two figures, presumably Generals Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee, shaking hands over the caption “Under ONE Flag.” Even the Sons of Union Veterans organization (Filii Veteranorum), established in the early 1880s, are postcard subjects.

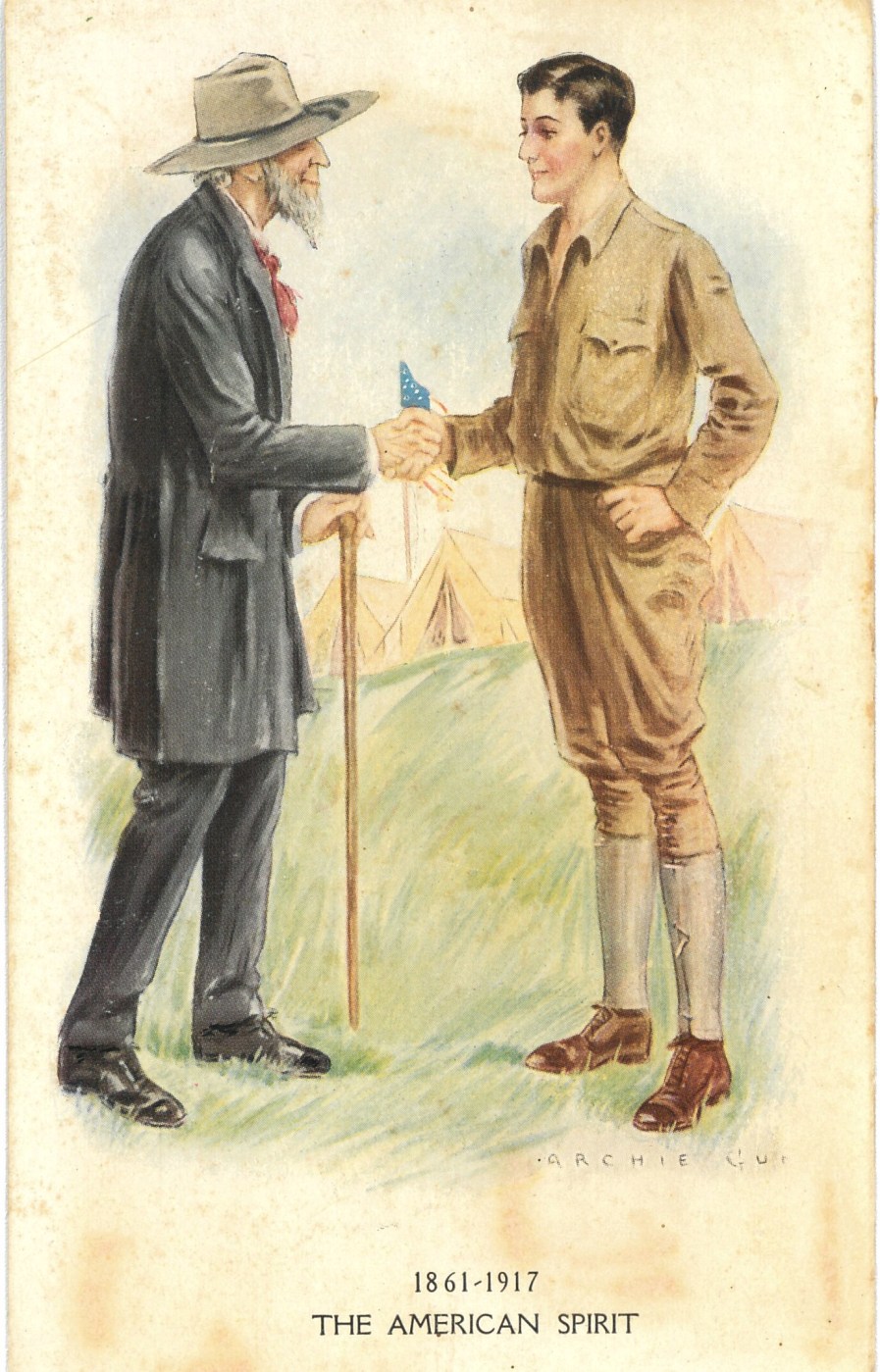

Memorial Day was established in 1868, but some imagery invokes all U.S. conflicts back to the American Revolution. The NCA collection has just one postcard referencing World War I, “1861-1917 / The American Spirit,” signed by ex-pat British graphic artist Archie Gunn who moved from drawing women to military subjects. Some Memorial Day cards eschewed Veterans or artifacts of war to simply emphasize the American flag and a general holiday greeting.

The popularity and significance of postcards as a research tool is a larger story not covered here and this glimpse at the narrow Memorial Day theme also overlooks how picture postcards help document the development of NCA’s oldest national cemeteries. The following examples from the NCA History Collection do illustrate how patriotic greeting postcards, as a trendy early twentieth-century form of correspondence or simple memento, was one way Americans commemorated Memorial Day.

Footnotes

- Jack H. Smith, Postcard Companion – the Collector’s Reference (Wallace-Homestead Book Co., Radnor PA, 1989), 9. Deltiology Definition & Meaning – Merriam-Webster. ↩︎

- The Journal of Education, 29 September 1910, Vol. 72, No. 11 (1797), 298. ↩︎

- TuckDB Postcards: A free database of antique postcards published by Raphael Tuck & Sons. ↩︎

- Sally S. Carver, The American Postcard Guide to Tuck (Carves Cards, Brookline MA, 1976), 36, 52. ↩︎

By Sara Amy Leach

Senior Historian, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

A Brief History of the Board of Veterans’ Appeals

On July 28, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6230 creating the Board of Veterans’ Appeals (BVA). The BVA was created as part of the Veterans Administration (VA), which had been established only three years earlier.

Featured Stories

The Fall of Saigon 1975: A South Vietnamese Military Physician Remembers

"There was chaos in the streets when I made my way to the hospital on the morning of April 30, 1975. In a place of order, there was now great confusion. The director and vice director of the hospital were gone, making me, the chief of medicine, the highest-ranking medical officer."