While suicide takes a toll on lives in every segment of society, Veterans in the post 9-11 era have statistically been more at risk than adults in the general population. VA’s efforts to combat the scourge of Veteran suicide owe a significant debt to the foundational research studies conducted by two VA psychologists in the 1950s. The work of Drs. Edwin S. Shneidman and Norman J. Farberow led to some of the earliest crisis intervention programs at VA and elsewhere and the establishment of the nation’s first dedicated Suicide Prevention Center in Los Angeles, California.

The VA and its predecessor organizations made great strides in the treatment of mental ailments stemming from military service during the twentieth century. After World War I, the Veteran’s Bureau established the first specialized neuropsychiatric hospitals to care for Veterans recovering from the trauma of war. In the decade after World War II, the Veterans Administration expanded its capacity to treat Veterans with mental health disorders, operating 40 neuropsychiatric hospitals and providing out-patient services at dozens of clinics.

VA also capitalized on its new academic affiliations program to connect its hospitals with the latest advances in medical school training. Despite all of the resources devoted to improving the mental well-being of Veterans, however, the subject of suicide received scant attention within VA or the larger community of mental health professionals. In an unpublished manuscript, Dr. Ferberow described suicide as “a long- neglected, taboo-encrusted social and personal phenomenon.” By the mid-1950s, more than 20,000 people a year were dying by their own hands; yet, the issue was poorly understood and shrouded in guilt and shame.

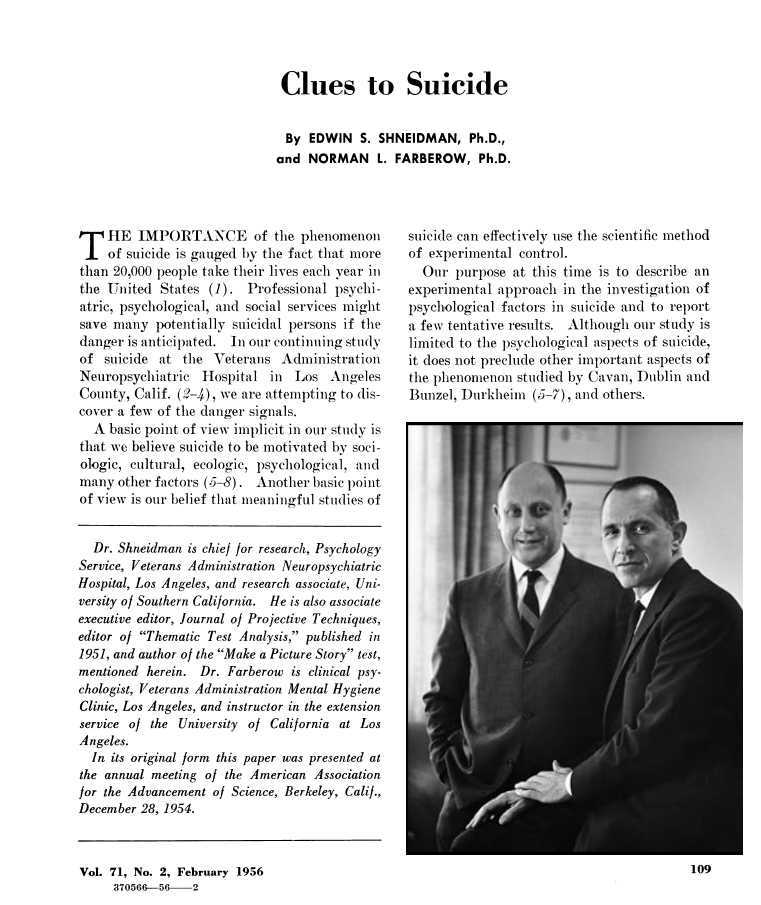

Farberow and Shneidman, both psychologists working at VA facilities in Los Angeles, embarked on their joint investigation into the psychological aspects of suicide after the latter stumbled on a trove of suicide notes in the city’s coroner office in 1949. They designed a three-part study using the notes, psychological test results, and psychiatric case histories of 128 Veterans who had been treated for mental health reasons at local VA hospitals.

The 128 subjects were split evenly among four categories: completed suicides, attempted suicides, threatened suicides, and non-suicides. They published the results of their research in a seminal paper titled “Clues to Suicide” that appeared in a 1956 issue of the journal Public Health Reports. One of the most important findings from their study was that most individuals who had died by suicide had previously attempted or threatened to take their lives. They also found that about half of the suicides occurred within 90 days after an individual had “passed an emotional crisis and . . . seemed to be on the way to recovery.”

The 1956 article was only one of the many publications Farberow and Shneidman authored jointly, individually, or in collaboration with other specialists on the topic of suicide throughout their long and prolific careers. (Both men lived into their nineties and remained active in their field almost to the end). Their research and writings transformed the study of suicide or “suicidology” into a recognized academic discipline.

As a result of their work, what was once regarded as a taboo topic became recognized as a vital public health threat. At VA, they served as the co-principal investigators at the agency’s Central Research Unit for the Study of Unpredicted Death for over a decade, analyzing suicidal behavior and risk factors among different types of patients. During the late 1950s, they also developed the theories about suicide prevention that would prove enormous influential within the profession. Starting from the premise that suicide was, in fact, preventable, they argued that the self-destructive impulses leading to suicide could be forestalled by timely detection, intervention, and treatment.

In 1958, Farberow and Shneidman were able to put their theories into practice in a clinical setting, teaming up with psychiatrist Robert E. Litman, to open the first Suicide Prevention Center in the United States. Staffed by psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers, the center became a model for others. Within 15 years of its founding, over 150 centers had been created throughout the country. The LA center added a 24-hour suicide hotline in 1963 and pioneered the practice of training non-professionals to take crisis calls. Since then, crisis hotlines have saved millions of lives worldwide

In 2007, in response to the rising suicide rates among Veterans, VA partnered with the Department of Health and Human Services to establish a Veterans Crisis Line manned around the clock by VA clinical staff. The same year, VA created suicide prevention coordinator positions at all VA medical centers. More recently, VA made suicide prevention its top clinical priority and released a comprehensive 10-year National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide. The VA plan builds on the concepts of the two VA psychologists who decades earlier set out to understand the dynamics of suicide and how to prevent such tragedies from occurring.

By Katie Rories

Historian, Veterans Health Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 90: Pearl Harbor Unknowns Marker

Seamen 1st Class Raymond Emory survived the attack on Pearl Harbor. Decades later, his research and advocacy led the government to add ship names to the markers of the Pearl Harbor unknowns interred in the National Cemetery of the Pacific.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 89: VA Film “You Can Lick TB” (1949)

In 1949, VA produced a 19-minute film titled “You Can Lick TB.” The film follows a fictional conversation between a bedridden Veteran with tuberculosis and his VA doctor, dramatizing through brief vignettes the different stages of TB treatment and recovery.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 88: Civil War Nurses

During the Civil War, thousands of women served as nurses for the Union Army. Most had no prior medical training, but they volunteered out of a desire to support family members and other loved ones fighting in the war. Female nurses cared for soldiers in city infirmaries, on hospital ships, and even on the battlefield, enduring hardships and sometimes putting their own lives in danger to minister to the injured.

Despite the invaluable service they rendered, Union nurses received no federal benefits after the war. Women-led organizations such as the Woman’s Relief Corps spearheaded efforts to compensate former nurses for their service. In 1892, Congress finally acceded to their demands.