“The beer hall is more attractive to a large number of the members than either the library or reading room.”

Edward Cobb, Civil War Veteran and resident, Southern Branch-National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers

Beer halls and beer gardens were familiar to Civil War Veterans who resided at branches of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (NHDVS). A predecessor to the modern VA medical campuses, the NHDVS system was established for Union Veterans after the war. The military-like setting included barracks-style housing, uniforms, formations, and a disciplinary system to maintain order. Veterans had assigned duties such as raising crops, tending the small herds of domesticated animals, and performing kitchen labor. Residents also formed marching bands and baseball teams, cultivated flower gardens, and engaged in a variety of other leisure and recreational activities. Many sites also established on-campus beer halls.

Alcohol consumption was commonplace among Civil War soldiers—and Veterans. This led to habitual intemperance among Veterans and incidents of drunkenness. NHDVS managers attempted to prevent residents from overindulging through rules limiting alcohol on campuses. Regulations also discouraged residents from frequenting establishments outside NHDVS gates willing to sell them as much liquor as they could consume. The creation of on-campus beer halls was an agreeable compromise for controlled access to alcoholic beverages.

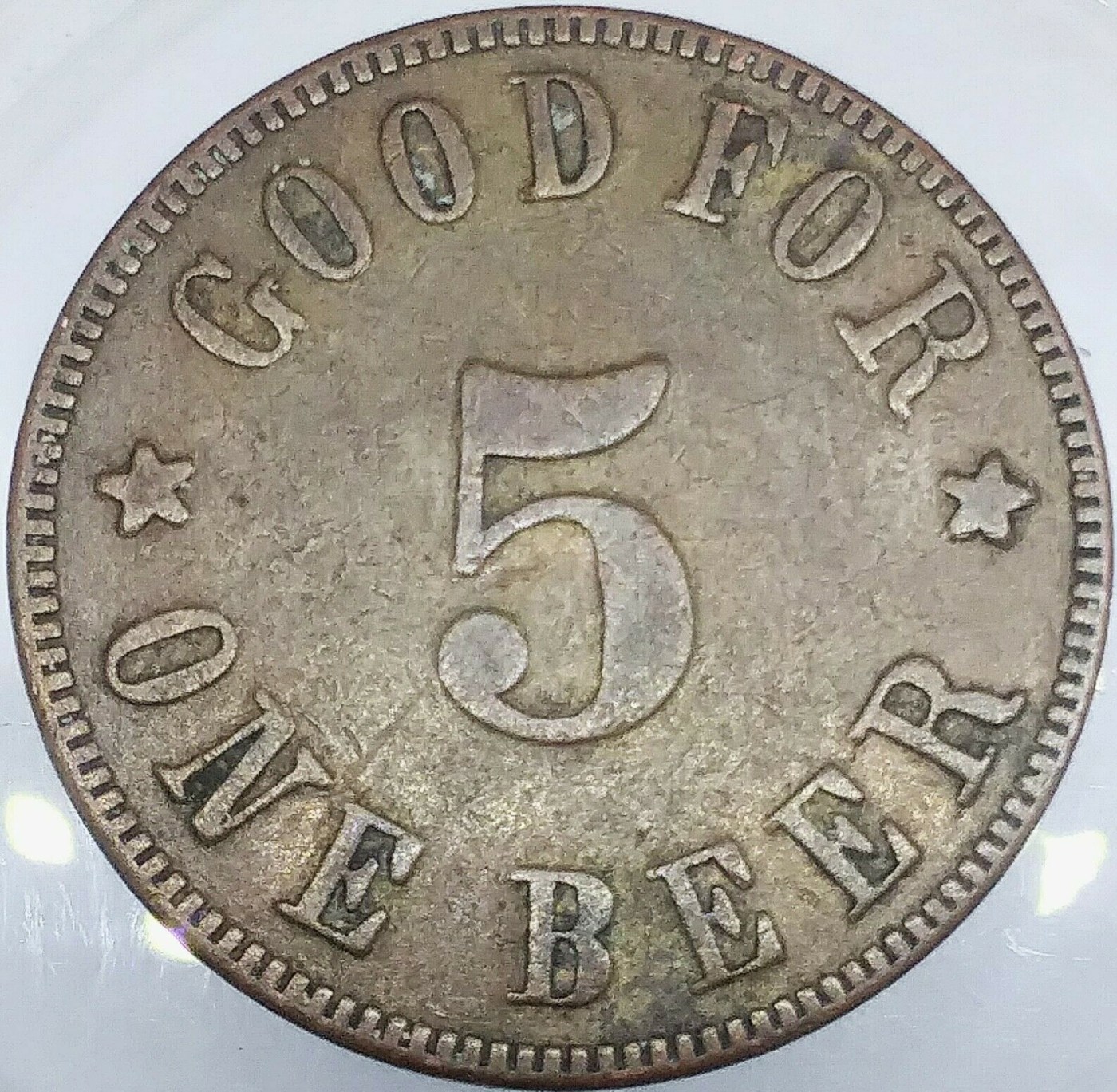

The Northwestern Branch-NHDVS in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, began selling beer on the grounds in the late 1870s. In 1887 the Central Branch in Dayton, Ohio, reported reduced rates of drunkenness and improved order after opening a beer hall. NHDVS administrators limited consumption in these beer halls by selling beer tokens or tickets that were exchanged for beer. The compromise was welcomed by administrators and Veterans alike.

Tokens were round and made of brass or other metals, usually less than one inch in diameter. They were produced for NHDVS sites by craftsmen like James Murdock, Jr., an engraver from Cincinnati, Ohio.

At the Southern Branch-NHDVS in Hampton, Virginia, resident Edward Cobb recalled, “The quality of beer is of the best, and the glasses are large. On pension day and for a week afterward, the place is crowded; the men [are] standing in long lines.”

In early 1907, as the prohibition movement gained momentum nationwide, Congress banned alcohol at National Homes, and the era of the beer halls came to an end. By this time, the number of Civil War Veterans was declining. After World War I, a new model of veteran care replaced the self-sustaining National Home campuses.

By Michael Visconage

Chief Historian, Department of Veterans Affairs

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.