The flat granite markers for the unknowns inscribed with their place of death and the ship they served aboard would not exist but for the efforts of one resolute sailor who survived the devastating surprise attack on the U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor.

On the morning of December 7, 1941, Seaman 1st Class Raymond D. Emory was reading the newspaper aboard USS Honolulu (CL-48), docked at Pearl Harbor’s Navy Yard near Battleship Row, when he heard general quarters sound. Springing up a ladder, he was deafened by machine gun fire when he got topside and thought to himself, “This is a really good drill.”

Emory, who manned a machine gun during the attack, was forever marked by what he witnessed. “There hasn’t been a day in my life that I haven’t thought about that day,” he said in a 2015 interview.

Half a century later, when Emory visited the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, also known as the “Punchbowl,” in Honolulu, Hawaii, he found to his chagrin that the gravesites of his fallen comrades merely identified them as unknowns from December 7, 1941. This spurred the former sailor to begin a lobbying campaign to have the government add ship names to the markers and exhume the remains of those who could potentially be identified.

Emory became a one-man research army, spending countless hours digging into the original burial records. He soon discovered that the paucity of detail on the markers stemmed from the fact that most of the Pearl Harbor dead were originally buried at Nuuanu and Halawa Naval Cemeteries. They were subsequently reinterred at the Punchbowl in 1949, but the original burial records were not consulted when this happened.

Emory’s research showed that, even when the deceased could not be identified, the name of the ship the body was recovered from was easily ascertained. Yet, this information was not included on the grave markers. With dogged determination, Emory walked the cemetery grounds with a pencil and clipboard in hand, finding 265 gravesites containing 653 remains. He was then able to match each one with the historical records, thus making it possible to include the ship’s name on each stone.

Armed with this information, Emory took his findings to several government agencies but was frustrated by the slow response. He then enlisted the aid of U.S. Representative Patsy T. Mink of Hawaii. Thanks to her intervention, the National Defense Authorization for fiscal year 2001 included a section stipulating the “addition of certain information to markers on graves containing remains of certain unknowns from USS Arizona who died in the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.”

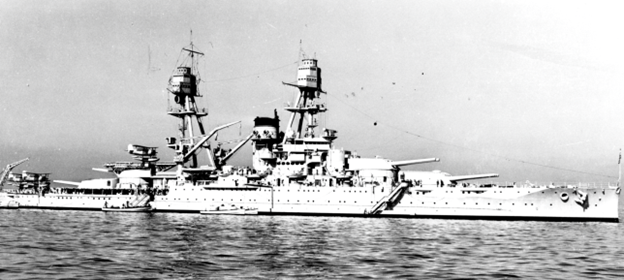

In August 2001, over 70 unknown markers were replaced with ones that included “USS Arizona” and “PEARL HARBOR.” By November 2002, 177 replacement stones had been installed that included the names of other Navy vessels that sank at Pearl Harbor: California, Curtiss, Nevada, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Utah, and West Virginia. When asked how he felt, Ray replied, “at least now they can tell where [those killed at Pearl Harbor] came from.”

Emory lived to see the fruition of his second wish as well. In 2015, the Pentagon began to exhume around 400 sailors and Marines from USS Oklahoma who had been buried as unknowns at 45 gravesites. Since then, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) has identified 362 unaccounted crew members of Oklahoma. Additionally, DPAA analyzed the remains of 25 sailors from USS West Virginia and determined the identity of 20 of them.

In 2018, Ray decided to leave his Hawaii home to move back to Idaho after the death of his wife. Before departing, he paid one last visit to Pearl Harbor and was shocked to find more than 500 sailors formed in an honor cordon, cheering and praising the grizzled old Veteran for what he had accomplished.

“Ray, you’re the man that did it. There’s nobody else. If it wasn’t for you, it would have never been done,” the Navy’s liaison told Emory during the brief ceremony. On August 20, 2018, Ray passed away and was interred at Honolulu’s Diamond Head Memorial Park, fewer than ten miles from the Punchbowl and the Pearl Harbor victims he spent his final years honoring.

By Jimmy Price

Historian, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.