Born October 12, 1919, in Waco, Texas, Miller joined the Navy in 1939 as a mess attendant one of the only occupational specialties then open to a Black man. In January 1940, he was assigned to the battleship USS West Virginia (BB 48), stationed at Pearl Harbor. Severe damage to the ship during the early phases of the December 7th attack prevented Miller from manning his assigned battle station. Seeking to help where he could, he was ordered to the ship’s bridge to help move his captain, Mervyn Bennion, mortally wounded with shrapnel in his abdomen.

Doris Miller was then ordered to the port side anti-aircraft guns to load ammunition for an officer. After performing this task, Miller, on his own initiative, loaded and manned an unattended gun and fired at incoming Japanese planes. Although untrained, he laid down effective fire and stopped firing when he ran out of ammunition and the ship began to sink. Even then, he persisted in helping his fellow sailors to safety until he finally made his way to shore.1 Miller, himself, escaped injury and was reassigned to the cruiser Indianapolis (CA 35).

Initially commended only as an unnamed Black man, pressure from the NAACP led to Doris Miller’s identification and the presentation of an award. On April 2, 1942, Miller’s efforts on the West Virginia were dramatized on the CBS radio series, They Live Forever.2 Although Congressional bills and other calls to grant Miller the Medal of Honor failed, President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved awarding Miller the Navy Cross. Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet, presented the Navy Cross to Miller on board the USS Enterprise (CV-6) on May 27, 1942.

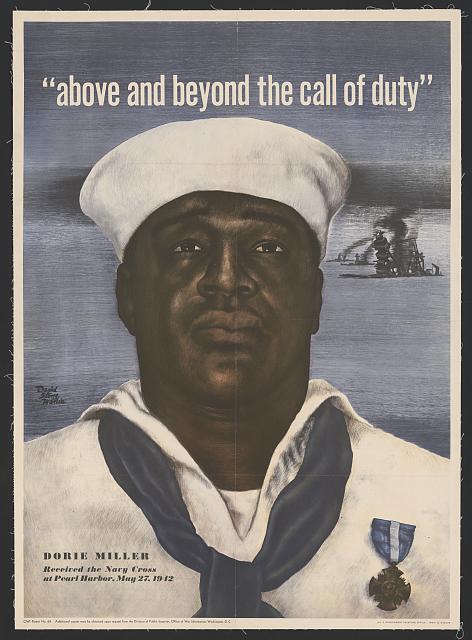

The Navy detached Miller to participate in a War Bond tour with White war heroes from December 1942 to January 1943, making him the first African American allowed on the speaking tour.3 Furthermore, his portrait appeared in a 1943 Navy recruiting poster under the words “above and beyond the call of duty.”4

Miller was assigned to the escort carrier USS Liscome Bay (CVE 56) in June 1943 and returned to the war.5 His ship was struck by a torpedo fired from a Japanese submarine on November 24, 1943, during the Battle of Makin in the invasion of the Gilbert Islands. The explosion detonated the ship’s aviation bomb magazine creating a devastating explosion. The ship sank in 23 minutes. Over 600 of a crew of 900 were lost, including Miller. His parents were notified of their 24-year-old son’s loss on the second anniversary of Pearl Harbor.

While begrudgingly recognized, Doris Miller became a role model and served as a rallying cry for desegregation in the United States Armed Forces. Miller was not keen on the national attention and cautiously optimistic about the standing of African Americans in the military in the future. In one of his few letters to the Pittsburgh Courier he wrote, “you have opened up a little for us, at least for the ones who were following me, and I hope it will be better in the future.”6

Since his death nearly 80 years ago, Doris Miller continues to be recognized posthumously for his patriotism and extraordinary bravery. Two more recent examples are: On December 18, 2014, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) honored Miller for his heroism by naming the VA medical center in Waco, Texas, after him.7 On January 19, 2020, the U.S. Navy announced construction of the aircraft carrier USS Doris Miller (CVN-81), an honor traditionally reserved for U.S. Presidents or other high ranking individuals.8 The ship is scheduled to be commissioned in January 2030.

Footnotes

- Cutrer, Thomas W., and T. Michael Parrish. “How Dorie Miller’s Bravery Helped Fight Navy Racism.” Navy Times, January 20, 2020, sec. Salute to Veterans. ↩︎

- Doris Miller – Wikipedia. ↩︎

- Doris Miller, Military History Fandom Wikipedia. ↩︎

- 1943 U.S. Navy recruiting poster featuring Miller and his Navy Cross. ↩︎

- Cutrer and Parrish. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Flores, Bill. “H.R.4199 – 113th Congress (2013-2014): To Name the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Waco, Texas, as the ‘Doris Miller Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center’” December 18, 2014. 2013/2014. ↩︎

- Doris Miller Wikipedia, from LaGrone, Sam (January 18, 2020). “Next Ford-class Carrier to be Named After Pearl Harbor Hero Doris Miller”. USNI News. Retrieved January 18, 2020. ↩︎

By Robert Cook

VA History Office intern, Pennsylvania State University graduate student, ROTC cadet and Army Veteran

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

A Brief History of the Board of Veterans’ Appeals

On July 28, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6230 creating the Board of Veterans’ Appeals (BVA). The BVA was created as part of the Veterans Administration (VA), which had been established only three years earlier.

Featured Stories

The Fall of Saigon 1975: A South Vietnamese Military Physician Remembers

"There was chaos in the streets when I made my way to the hospital on the morning of April 30, 1975. In a place of order, there was now great confusion. The director and vice director of the hospital were gone, making me, the chief of medicine, the highest-ranking medical officer."