In the first minutes of July 30, 1945, two torpedoes fired from Japanese submarine I-58 struck the starboard side of USS Indianapolis (CA 35). The first torpedo ripped off the ship’s bow and the second hit crew berthing areas, also knocking out communications. Within fifteen-minutes, the decorated warship began its descent to the bottom of the Philippine Sea. Around 300 crew died in the initial blasts or were trapped and went down with their ship. Between 800-900 went into the water.

Indianapolis had just completed her top-secret delivery of atomic bomb components to Tinian, an island in the Northern Marianas, days earlier and was now returning to the Philippines unescorted to prepare for the invasion of mainland Japan. Damage prevented transmission of a distress signal and misunderstood directives led to the Navy not reporting the ship’s failure to arrive. The Sailors and Marines who went into the water had only their shipmates for support.

The pilot of a U.S. Navy Lockheed PV-1 twin-engine patrol bomber located the survivors in the water by pure chance after spotting an oil slick while adjusting an antenna the afternoon of August 2. The men had been adrift for four days. A massive air and surface rescue operation ensued over the course of that night and through the following day. Out of 1,195 men, only 316 survived the ordeal, four additional Sailors were rescued but died shortly after.

The survivors faced incomprehensible misery. They were scattered miles apart in seven distinct groups. Some were fortunate to have gone in the water near rafts and floating rations. Others, including the largest group of around 400, had nothing but their life vests and floater nets. Men suffered from exposure, severe dehydration, attacks by hallucinating shipmates, exhaustion, hypothermia, and shark attacks. Many drank sea water, initiating a horrible death.

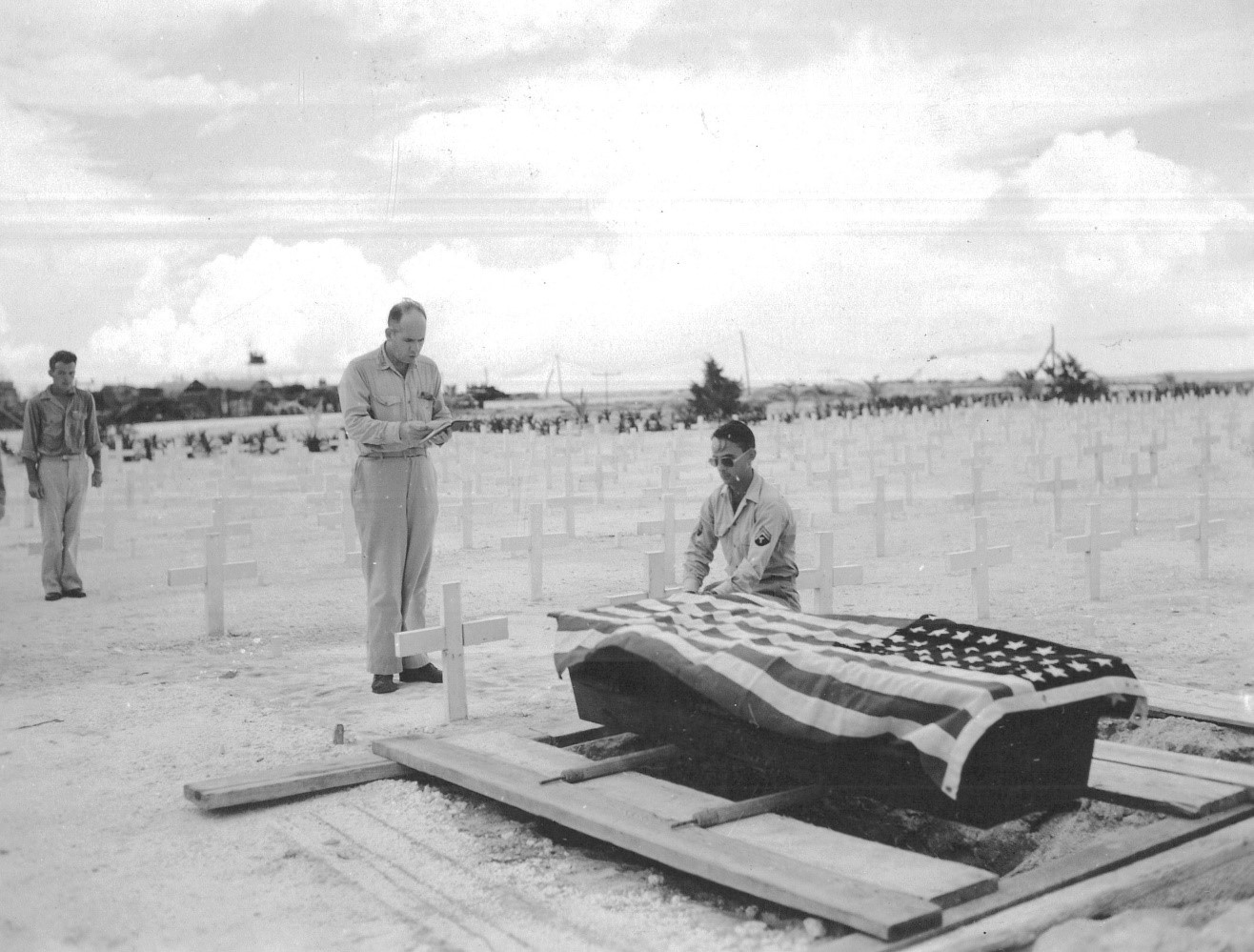

Those of the crew that went down with the ship or died in the water are memorialized on the Walls of the Missing in the American Battle Monuments Commission’s Manila American Cemetery. Forty-eight survivors rest in the NCA’s national cemeteries. Riverside National Cemetery, California and Fort Snelling National Cemetery, Minnesota represent the largest groupings of these Veterans. On May 9, 2021, survivor James Wesley Smith, S2c was interred in Mountain Home National Cemetery, TN. Only five survivors from the disaster were still living as of June 2021.

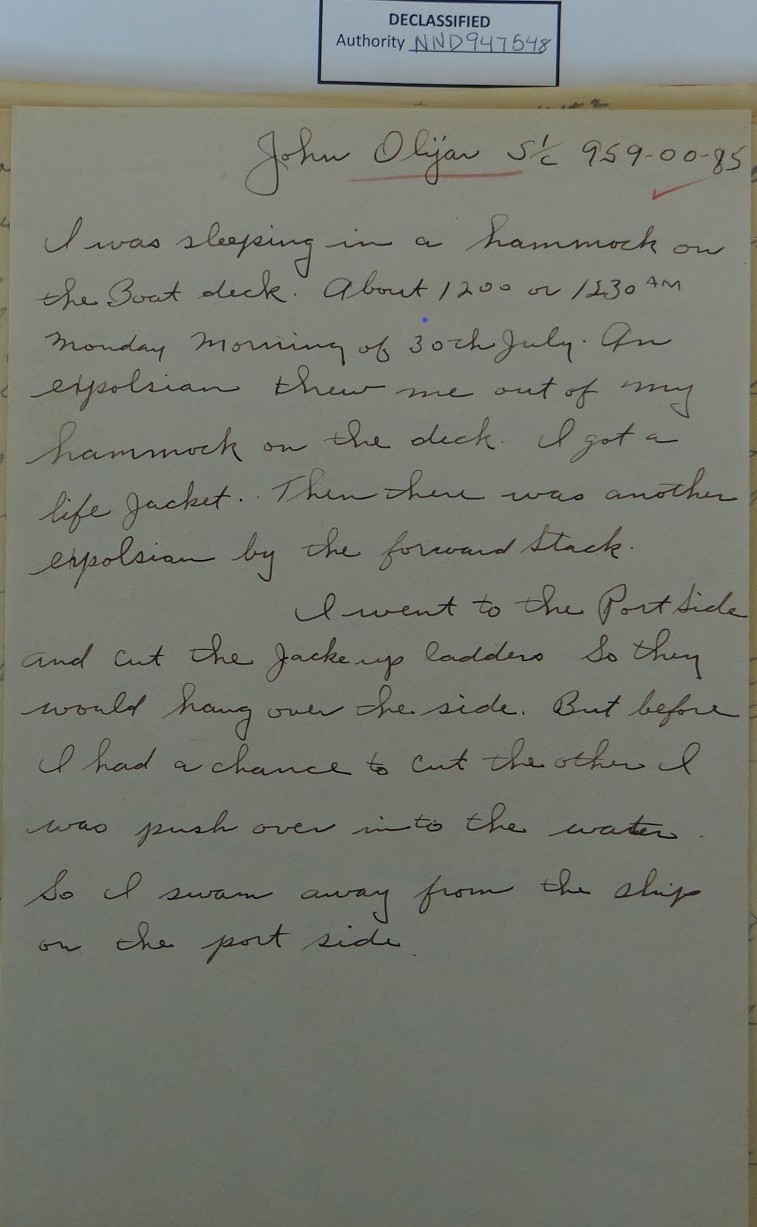

Transcription: “John Olijar S1/c 959-00-85, I was sleeping in a hammock on the Boat deck. About 1200 or 1230 AM Monday morning of 30th July. An explosion threw me out of my hammock on the deck. I got a life jacket. Then there was another explosion by the forward stack. I went to the Port Side and cut the Jacke up ladders so they would hang over the side. But before I had a chance to cut the other I was push over into the water. So I swam away from the ship on the port side.”

On the 75th anniversary of the sinking, surviving crewmembers were virtually presented with the Congressional Gold Medal. The presentation coincided with their annual reunion. It is important to reflect on the service and experience of Indianapolis’s final crew, give thanks to those still with us, and remember those who passed. Their seamanship brought the delivery of components for the atomic bomb Little Boy to Tinian which hastened the end of World War II. Additionally, their ordeal compelled the Navy to make improvements that undoubtedly saved the lives of countless Sailors and Marines.

By Richard Hulver, Ph.D.

Historian, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

A Brief History of the Board of Veterans’ Appeals

On July 28, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6230 creating the Board of Veterans’ Appeals (BVA). The BVA was created as part of the Veterans Administration (VA), which had been established only three years earlier.

Featured Stories

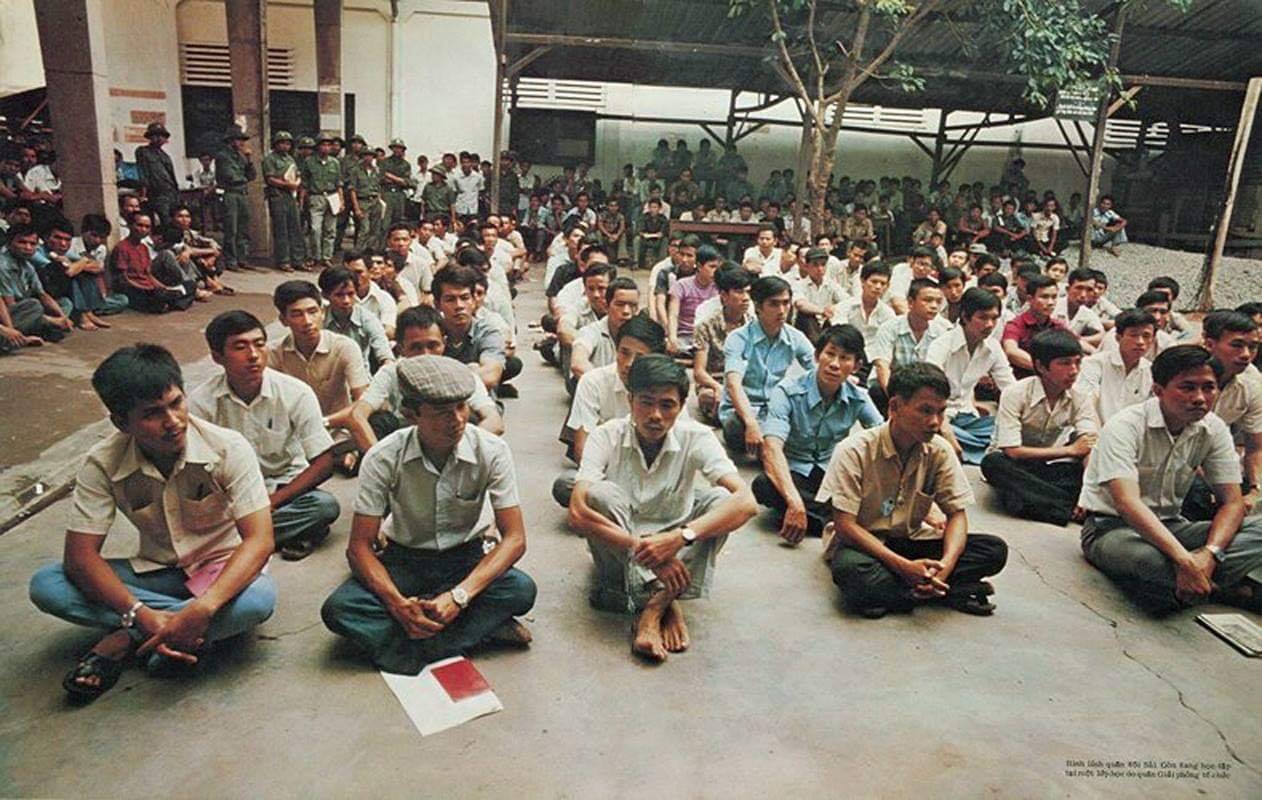

The Fall of Saigon 1975: A South Vietnamese Military Physician Remembers

"There was chaos in the streets when I made my way to the hospital on the morning of April 30, 1975. In a place of order, there was now great confusion. The director and vice director of the hospital were gone, making me, the chief of medicine, the highest-ranking medical officer."