During World War I and afterwards, the United States provided more than just hospital care for sick and wounded soldiers. Medical authorities also committed to rehabilitating the disabled so they could resume productive lives in the civilian workforce. The emerging field of occupational therapy played a crucial role in the rehabilitative process. Occupational therapy programs at Army and Veterans hospitals were organized around a simple principle: that engaging patients in everyday activities, from weaving and carpentry to metalwork and gardening, could hasten their physical, mental, and emotional recovery from the scars of war.

By the time the United States joined the conflict in April 1917, other nations had accumulated more than two years of experience caring for the wounded and managing their rehabilitation. The Army modeled its rehabilitation efforts on the Canadian and English examples. Both countries employed curative workshops to help restore injured soldiers to health. The War Department adopted a similar policy, directing “the use of work, manual and mental, . . . during convalescent period” for personnel in military hospitals. By work, Army officials meant occupational activities designed to improve a patient’s physical and cognitive functions by exercising the body and mind.

The Army implemented a trial rehabilitation program that incorporated occupational therapy at Walter Reed General Hospital in Washington, D.C., in early 1918. Before the armistice ended the war in November 1918, the number of stateside Army hospitals dedicated to rehabilitation and occupational therapy had grown to 17. The total expanded to 45 in April 1919 as over 100,000 disabled soldiers returned home from service overseas.

From the start, surgeons and clinicians claimed occupational therapy as a medical function, to be carried out in a hospital setting under the supervision of the ward doctor. As one Army medical officer explained in the Journal of the American Medical Association, “it is the surgeon or physician who must indicate the particular function to be restored and to prescribe the dose of work, the time it is to be given and the frequency of its repetition.” Women trained in occupational therapy techniques served as reconstruction aides. They provided the hands-on guidance and instruction.

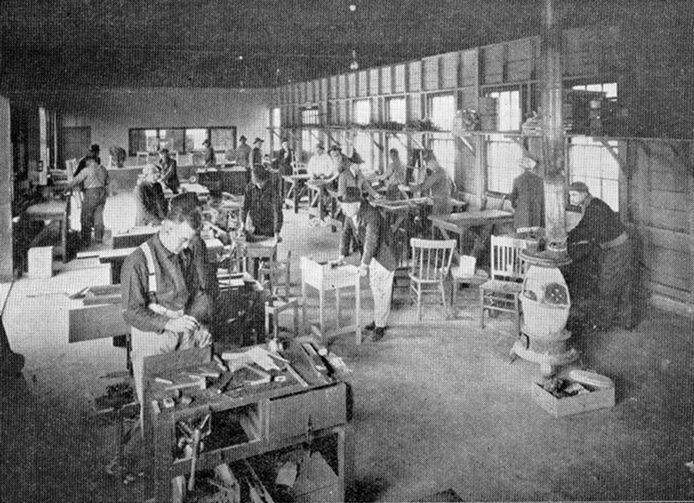

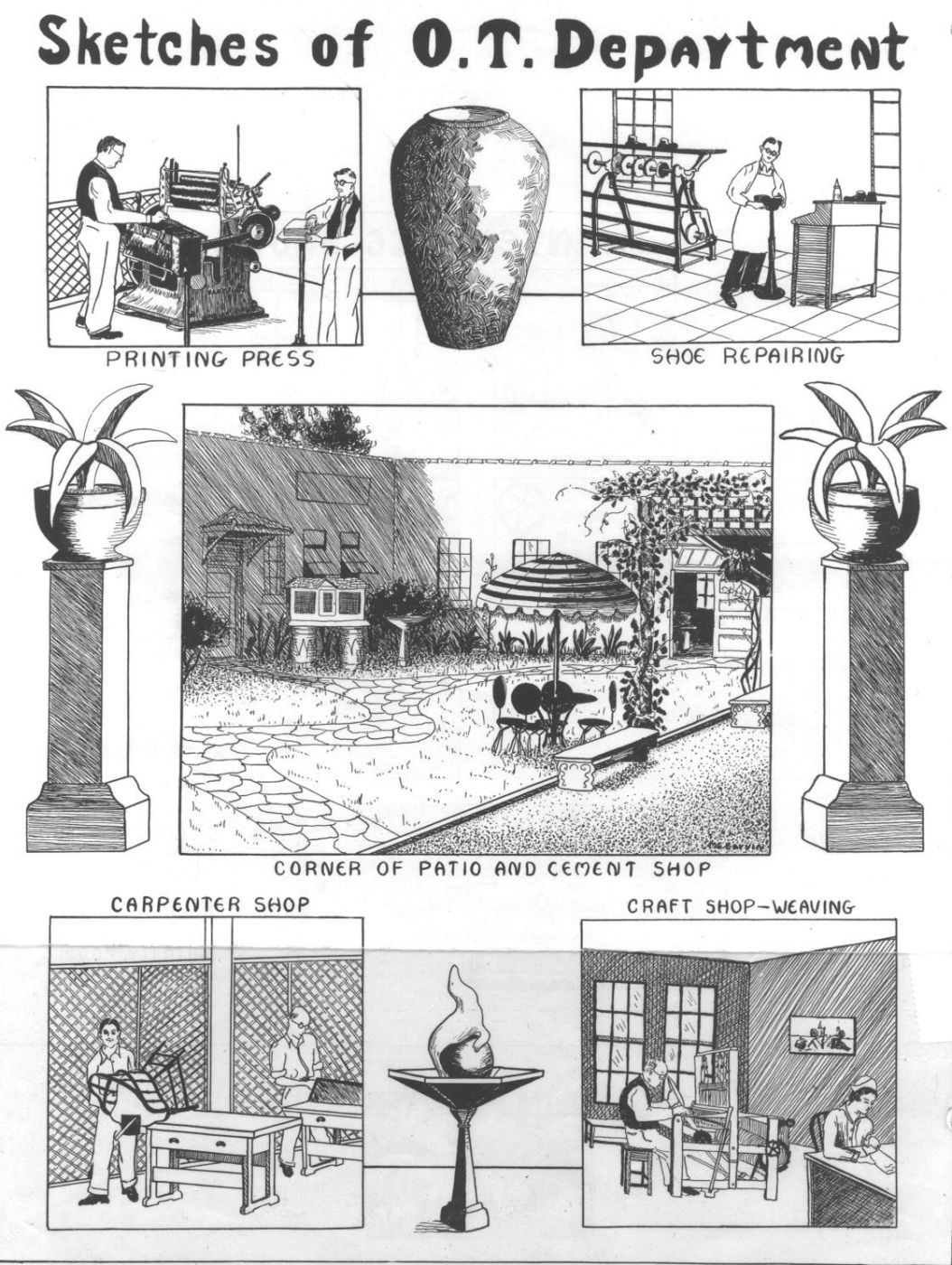

The tasks assigned to patients depended on their medical condition and aptitude. Patients confined to bed or wheelchairs performed what was called ward work, which included knitting, basketry, beadwork, and other handicrafts. Some were also permitted to take courses of a vocational nature in such subjects as typewriting, shorthand, and bookkeeping. Ambulatory patients could engage in more physically demanding shop and outdoor work. The activities prescribed for these men ranged from shoe repairing and harness making to landscaping and dairy farming.

Occupational therapy continued to be a cornerstone of the treatment regimen for the disabled after the war when first the Public Health Service and then the Veterans Bureau assumed responsibility for the care of Great War Veterans. The Public Health Service organized a Reconstruction Section in July 1919 to direct the operations of occupational and physical therapy aides at its hospital facilities. Three years later, it passed the baton to the Veterans Bureau, which rapidly organized an agency-wide rehabilitation program to serve Veterans still suffering from war-related injuries or ailments. By the mid-1920s, almost 10,000 patients on average were receiving occupational therapy treatments in Veterans Bureau hospitals. This work was overseen by a dedicated staff of about 300 instructors, aides, and assistants.

Agency physicians tailored occupational therapy activities towards the type of patients a particular hospital served. Hospitals specializing in the treatment of tuberculosis generally focused on handicrafts and other more sedentary pursuits due to the need to limit the physical activity of patients in the active stage of the disease. Even for those on bedrest, though, therapy furnished diversion and had a calming effect on the mind. “[B]y rendering the patient more contented, it increases the effectiveness of all else that is done for him,” the chief of occupational therapy observed in the agency’s journal, the Medical Bulletin. As patients improved through treatment, they could take up progressively more challenging tasks. The list of activities recommended for TB patients in the ambulatory stage included cabinetmaking, bookbinding, photography, commercial art, and greenhouse gardening, to name just a few.

Veterans in neuropsychiatric hospitals, by contrast, were often prescribed “out-of-door” activities, including various kinds of agricultural work. Some patients showed little interest in craft making or other tasks that required sustained concentration. But they were usually in sound physical condition and many came from a farming background, which made agriculture an ideal form of therapy for them. Neuropsychiatric hospitals as a rule were in rural locations with ample acreage available for growing crops and raising livestock. The Veterans Bureau annual report for 1925 described some of the agricultural projects that were underway at its facilities: “The out-of-door occupations . . . have taken the form of dairying, swine raising, poultry raising, farming, gardening, and bee culture.”

These enterprises could yield a substantial economic return for the hospitals. The farm work at neuropsychiatric facilities produced fresh vegetables, milk, eggs, and poultry for their kitchens. The 1926 annual report calculated the value of these products at $80,000. Hospitals also saved on maintenance and operating costs through other occupational therapy activities conducted by patients, such as carpentry, cabinet work, and cement construction. Additional earnings were generated through the sale of toys, chairs, baskets, and other household items created by Veterans in hospital workshops.

The bottom line, however, remained the welfare of the Veterans receiving the rehabilitative treatment. As one Veterans Bureau physician phrased it, “the greatest and most valuable returns . . . will be measured in terms of therapeutic benefits accruing to the patients, which can not be analyzed on a dollar and cent basis.”

By Jeffrey Seiken, PhD

Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.