The Constitution requires the government to conduct a census of the population every ten years to determine taxation and representation in Congress. Early on, though, federal officials began using the census to collect other kinds of data beyond simple headcounts. The 1840 census was the most expansive to date, surveying inhabitants about their occupation, education, literacy, and select disabilities. In another first, the 1840 census also recorded the name, age, and place of residence of persons receiving a government pension. Congress published this information in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

Congress added a line of questioning about pensioner status to the 1840 census schedule as a result of a last-minute request from the Commissioner of Pensions, James L. Edwards. As head of the Pension Office, Edwards reported annually to the War Department on the number of pensioners on its books. In the 1830s, over 31,000 names had been added to the list due to the series of laws passed during the decade that awarded pensions to almost all living Revolutionary War Veterans or their widows. At the time Congress was working on the census bill in February 1839, the most recent statement from Edwards put the total number of pensioners at over 40,000.

From year to year, the payments owed many persons on the pension list went uncollected, probably because they were deceased. However, the Pension Office had no way of knowing this unless it received notification of a death. Edwards wanted the U.S. marshals and their assistants, who were going door to door asking questions for the 1840 census, to identify pensioners living in the household as well. “This mode of discovering the name of all who yet survive seems to me to be well calculated to purge the pension rolls,” Edwards wrote to the Secretary of War, who endorsed the suggestion and passed it on to President Martin Van Buren. The president recommended the proposal to Congress.

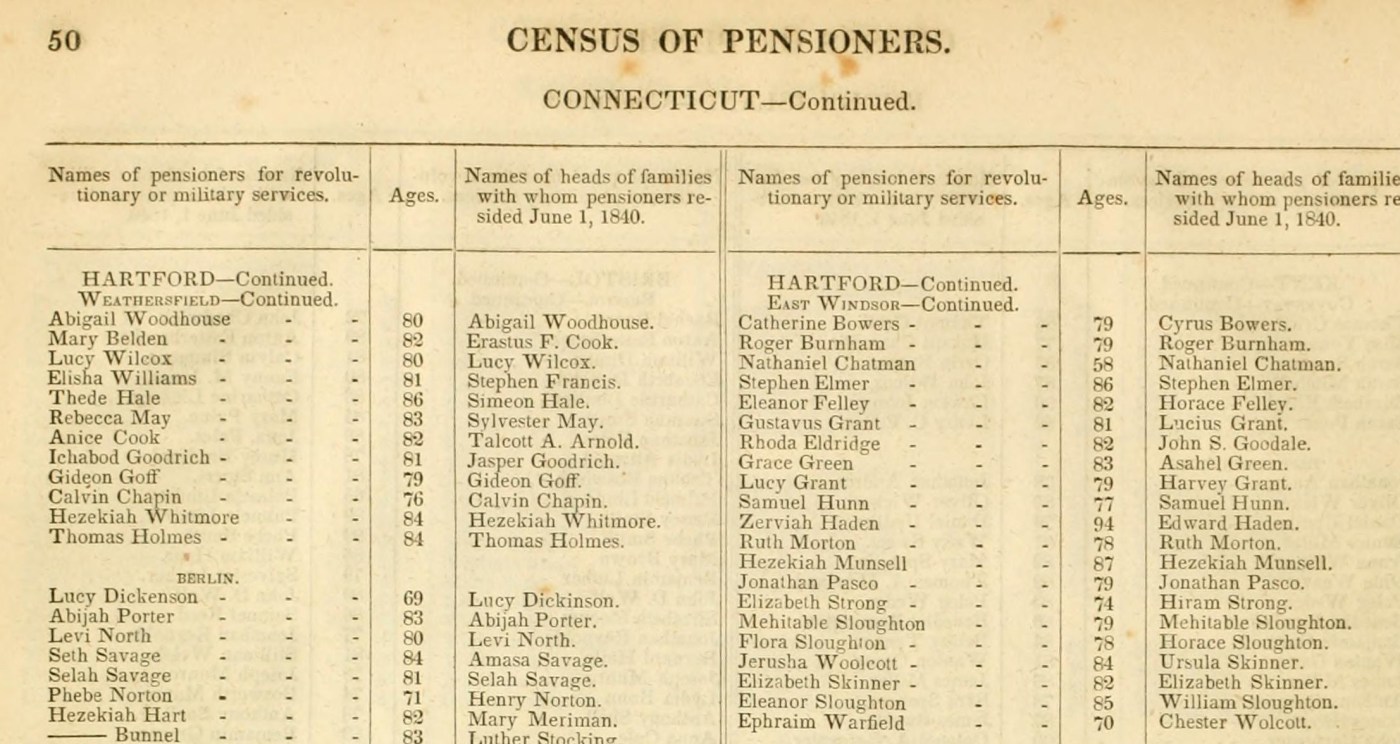

The “Census of Pensioners” in its published form contained no introductory or explanatory text. The 195-page volume was organized by state, county, and township, and listed the pensioners alphabetically by name within each location. It also stated their age and the name of the person with whom they resided, but did not say anything about their military service or provide other biographical data.

Given that 57 years had elapsed since the end of the Revolution, it should come as no surprise that the pages of the census were filled with septuagenarians, octogenarians, nonagenarians, and even a few centenarians. At age 94, Zerviah Haden of East Windsor, Connecticut, was one of the older persons to appear in the volume. According to the records available in her pension file, her husband Danial, whom she had married in 1768, served several short stints in the Connecticut militia during the early years of the Revolution. He died in 1815; 32 years later she obtained an annual pension of $55 under the 1836 law for Revolutionary War widows. She was living with a family member, possibly a grandson, when a census official visited her household and took down her information. In a poignant twist, she died just a few week later, on July 8, 1840.

Pensioners under the age of 70 can also be found in the census, but they are present in far fewer numbers. This was because the benefits laws that applied to Veterans who served after the Revolution were much narrower in scope. At this point in time, Congress only granted pensions to those who had been disabled in the line of duty. Widows’ pensions were likewise reserved for women whose husbands had died as a direct result of their military service. Even in the absence of identifying information, it seems safe to assume that most of the individuals named in the census between the age of 35 and 70 were Veterans or widows of the War of 1812. Some 7,000 Americans were killed or wounded in that conflict.

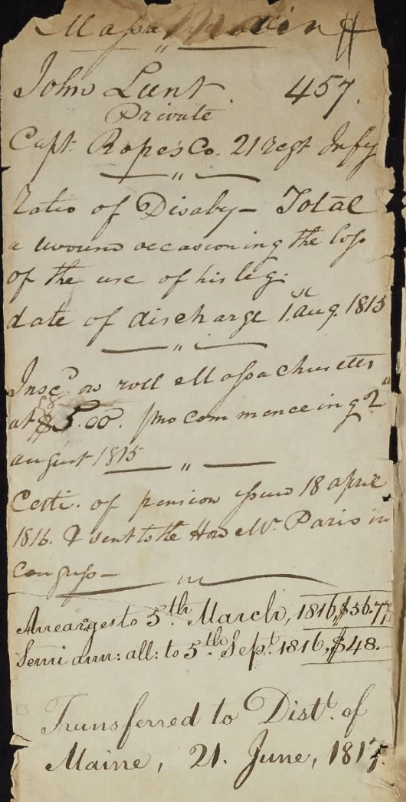

John Lunt, age 54, of New Gloucester, Maine, is representative of the War of 1812 cohort of pensioners. As documented in his pension file, he enlisted as a private in an infantry regiment and was wounded at the battle of Fort Erie in Canada in 1814. He lost the use of his right leg and was declared completely disabled. The government pensioned him in 1816 at $60 a year, which was the going rate for enlisted personnel. After the war, he relocated from Massachusetts to Maine. The information gathered in 1840 for the general census listed him as head of a household of ten, three of whom earned their livelihood through farm work.

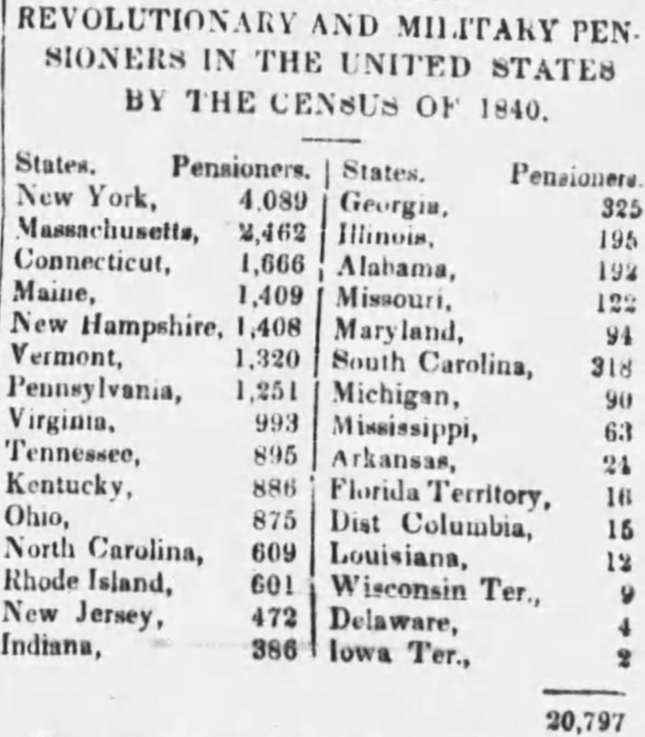

Government officers did not complete their work on the 1840 census until the following year. In September 1841, Congress ordered the printing of 10,000 copies of the “Census of Pensioners” and three other volumes of census statistics. When the number of pensioners was added up, the final tally came to 20,797, which was less than half of what the Pensioner Commissioner had been reporting to the Secretary of War in the most recent annual statements.

The discrepancy between the census data and the records maintained by Pension Office was significant. But after scrutinizing the returns of the census workers, Commissioner Edwards concluded that their reports were “too imperfect to be relied on.” He believed that pensioners were most likely undercounted for the simple reason that some people chose not to answer the questions put to them in a candid fashion. “The reluctance manifested by housekeepers,” he informed the Secretary of War, “on many occasions, to answer certain interrogatories, shows that much valuable information was withheld.” For the foreseeable future, the Pension Office would have to rely on its own less-than-precise accounting of the number of living and breathing pensioners on its rolls.

Congress waited fifty years before attempting another census of the Veteran population. And while Commissioner Edwards found the 1840 “Census of Pensioners” to be of marginal value, the publication later became a useful resource for genealogists researching their family history.

By Jeffrey Seiken, PhD

Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 93: Occupational Therapy Floor Loom

During World War I and afterwards, the United States committed to rehabilitating sick and wounded soldiers so they could resume productive lives in the civilian workforce. The emerging field of occupational therapy played a crucial role in the rehabilitative process.