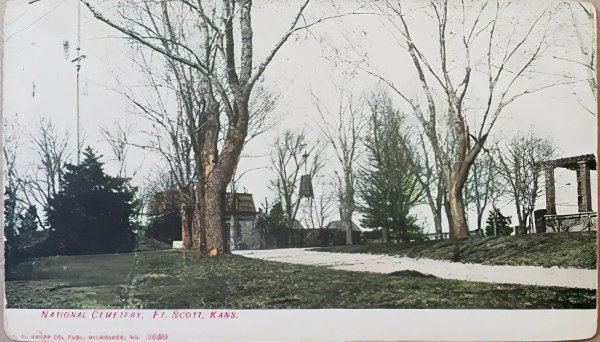

Maintaining a welcoming environment for the visiting public and mourners was, and remains, a key mission of national cemeteries. Within the first decades of their establishment, the superintendent’s lodge was important to this experience. Government regulations ordered the placement of signs near cemetery entrances telling visitors they were “invited to enter the office in the superintendent’s lodge, where a register is kept, and where information concerning this cemetery will be cheerfully furnished.”

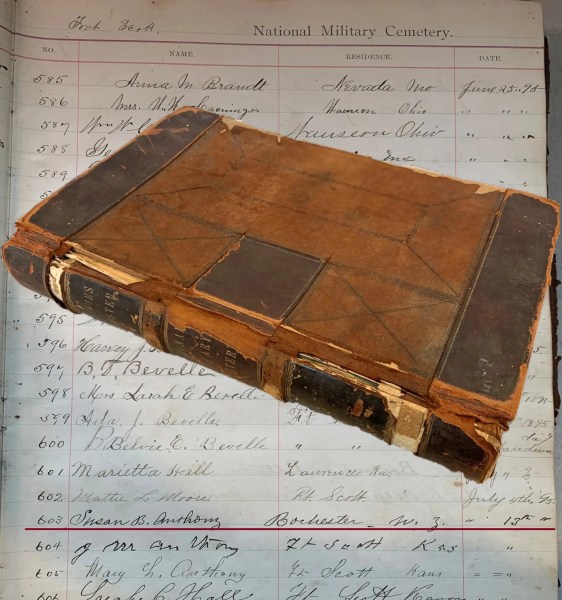

Lodges functioned as dual-purpose offices and residences for the superintendent (usually a disabled veteran) and his family. He was required to keep the building “neat and in good order” and “in a condition to receive visitors at all times.” A reception area was maintained in the office exclusively to accommodate visitors and to be occupied by the superintendent only for housekeeping purposes. A table with a leather-bound visitor register was a required feature of this area.

On July 13, 1895, renowned suffragist and social activist Susan B. Anthony visited Fort Scott National Cemetery, Kansas, along with her brother Jacob Merritt Anthony and his wife Mary, where they signed the ledger. Fittingly, the Anthony’s would have been hosted by Major George W. Ford, one of the national cemetery system’s only African American superintendents. Ford was a wounded veteran of the Indian Wars, civil rights advocate, and descendent of enslaved persons from George Washington’s home at Mount Vernon, Virginia. Ms. Anthony’s cemetery visit came during a stop at her brother’s Fort Scott home on her return east from a suffrage meeting in San Francisco, California.

Visitor registers provide a glimpse into the activity at national cemeteries and the individuals who passed through their gates. Unfortunately, few were preserved because Army regulations allowed them to be destroyed after they were filled, and by 1947 less-visited cemeteries were not required to use them.

By Richard Hulver, Ph.D.

Historian, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.