Many people interested in our progress have asked excellent questions how our archiving is going, what we are doing, how we are going to get there, and who we intend to be.

VA’s archives are both digital and physical

One of the earliest decisions I made as the VA History Office Senior Archivist was that digital and textual records would carry equal importance in the National VA History Center (NVAHC) Archives, and that the infrastructure was built at the same time. The truth is that digital materials are as fragile and at risk, just in a different way. Think about the 1990s through the mid-2000s, when we were saving everything to 3.5 inch disks and CD-ROM. Through time, hardware and software changes, and disks simply being thrown away, many of those records are simply gone.

This dual concept was important enough that when designing an image for the cover of NVAHCA’s Collections Management Plan, I asked our designer, Tessa Kalman, formerly of the Dayton VA Medical Center, to represent both of these priorities, and she did a beautiful job.

This balanced emphasis means we can serve a good portion of researchers now. Although we do not currently have the kind of physical working space that a researcher would expect, we can still meet at least some of those needs. For example, we have a French researcher working on mental health of returning soldiers. Because one of our collections is solely digital, we are able to respond to her faster than if we only focused on textual collections. It doesn’t make textual materials less important, rather there’s a value lost there if we focused on one aspect of our development. Our collections exist to serve researchers and that’s what we do.

How we serve researchers now and in the future.

How do we actually serve researchers in France, at universities, and in our own senior leadership? First, by developing an excellent CMP, which tells NVAHC Archives what and how, but also defines what researchers can expect and creates a level playing field for service. Then, researchers contact us, usually through the VAHO email vahistoryoffice@va.gov, with their request. One of the ways we aid research requests is the use of finding aids.

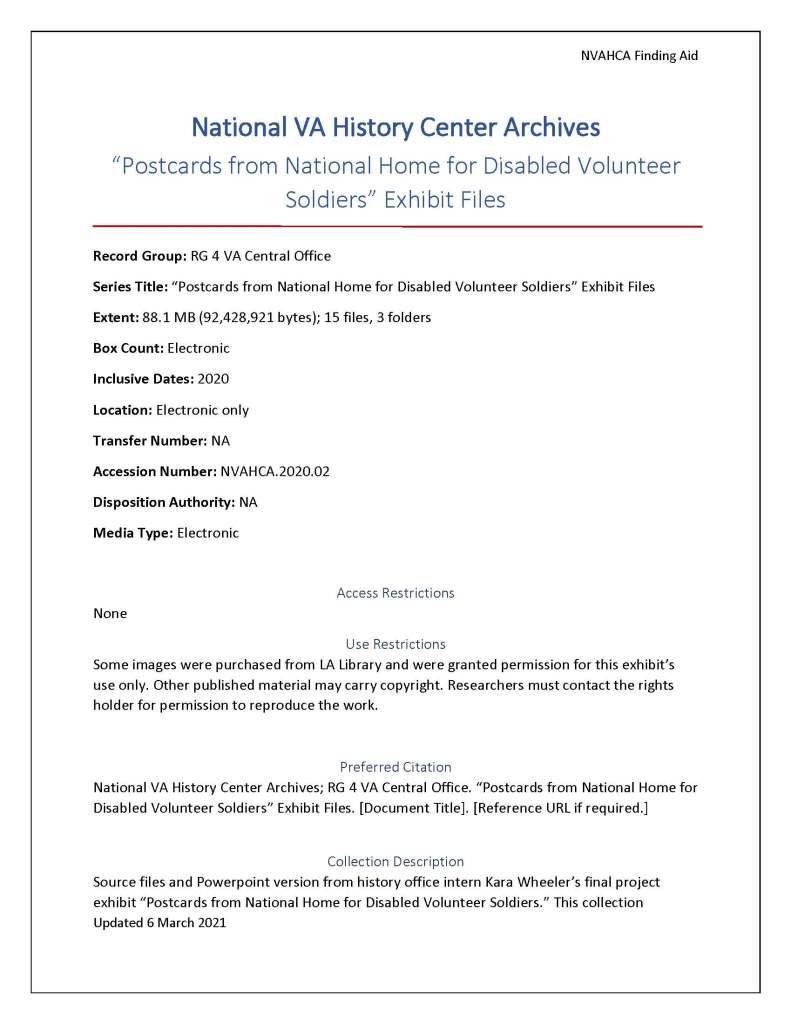

What is a finding aid? It’s a document that spells out everything about a collection. The example below (PDF, 2 pages) is from our Postcards Exhibit:

These give the researcher the opportunity to find materials they are looking for and to expand into areas they may not have considered.

Where will we be in a year?

By this time next year, it is a fervent hope that we will have the type of web presence allowing researchers to look through our finding aids and then request the specific documents they wish to see. Next year is too soon for a fully-fledged website that will enable them to pull the documents on their own, but that’s our desired long term end-state. The back-end analytics will allow us to maintain our metrics and glean information about where to further direct resources.

Why is the NVAHC important?

While the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) has long been responsible for collecting federal government documents, they are selective and only collect 3-5% of records, focusing mostly on the “what” of an agency’s work. At NVAHC Archives, we are interested in the answering “how did that happen.” We have a scope of collections and defined criteria (the CMP) that help ensure we stay within scope and provide researchers with unique material.

Ok, I read all that. Now show me something cool!

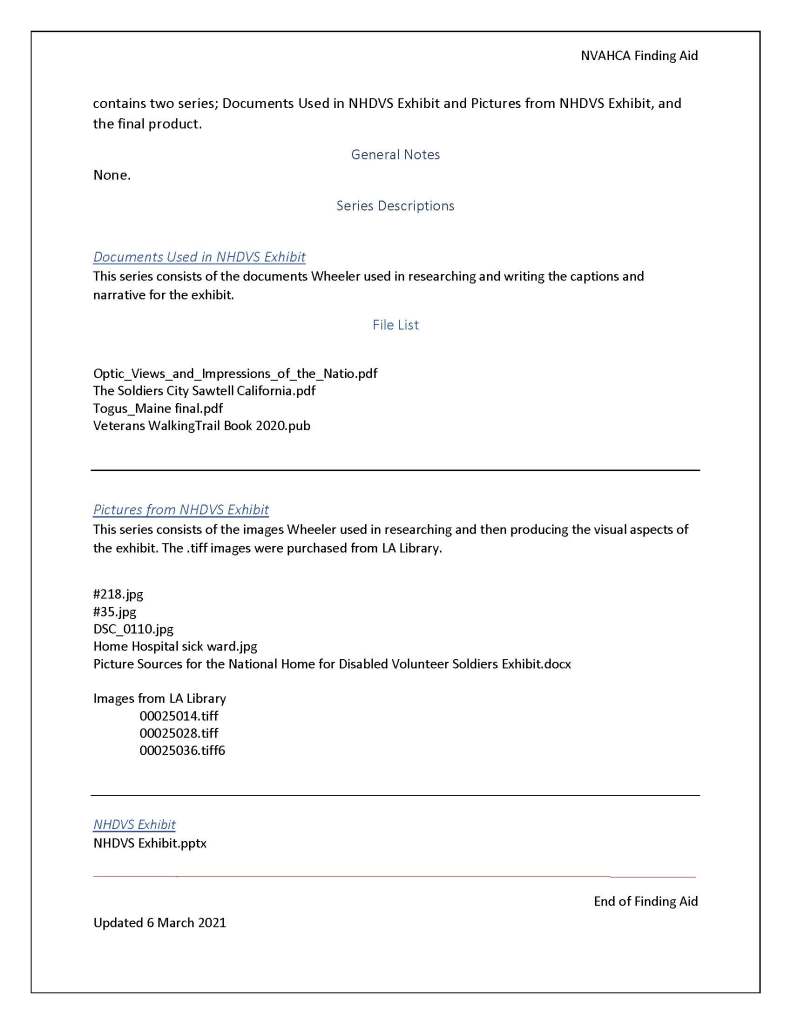

Below are images from a scanned souvenir program book (PDF, 25 pages) from the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, circa 1890.

At that time, the campus was a tourist attraction as well as a domiciliary. The booklet gives glimpses into what Veterans and tourists experienced. I wouldn’t call it Insta-worthy but you can very much see what things looked like at that time. A number of the buildings pictured still stand, including building 116 which will be part of the history center. Your prize is on the last page – you’ll know it when you see it!

Sources

- Archives Month Graphics

- Finding Aid (PDF, 2 pages)

- National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers souvenir program book, circa 1890 (PDF, 25 pages)

By Robyn Rodgers

Senior Archivist, National VA History Center

Share this story

Related Stories

Curator Corner

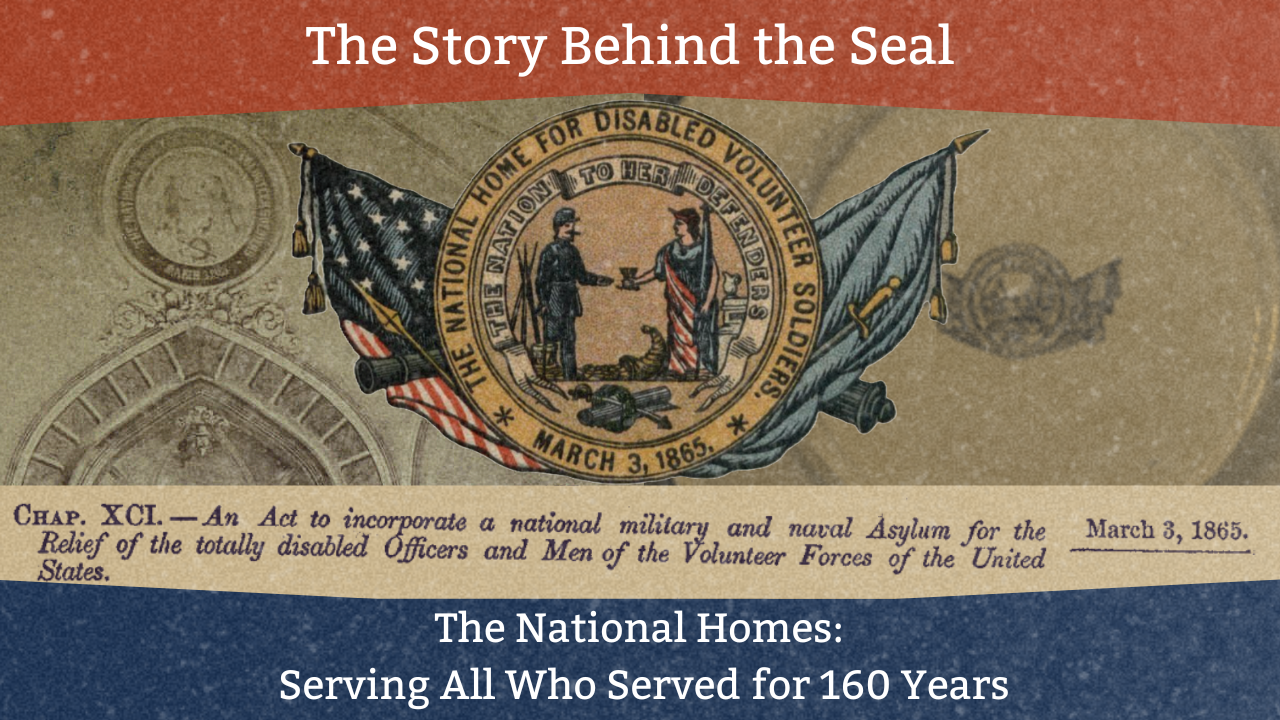

The Story Behind the National Homes’ Seal

The National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers turns 160 years old in 2025. The campuses are the oldest in the VA system, providing healthcare to Veterans to this day.

At the time of their establishment, they were the first of their type on this scale in the world. Within the NHDVS seal is the story that goes back 160 years ago.

Curator Corner

What’s in the Box? Fire Safety and Prevention at the National Homes

Fire safety may not be the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about Veteran care, but during the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers period (1865-1930), it was a critical concern. With campuses largely constructed of wooden-frame buildings, housing thousands of often elderly and disabled Veterans, the risk of fire was ever-present. Leaders of the National Homes were keenly aware of this danger, as reflected in their efforts to establish early fire safety protocols.

Throughout the late 19th century, the National Homes developed fire departments that were often staffed by Veteran residents, and the Central Branch in Dayton even had a steam fire engine. Maps from this era, produced by the Sanborn Map Company for fire insurance purposes, reveal detailed records of fire prevention equipment and strategies used at the Homes. These records provide us with a rare glimpse into evolving fire safety measures in the late 19th and early 20th Century, all part of a collective effort to ensure the well-being of the many Veterans living there.

Curator Corner

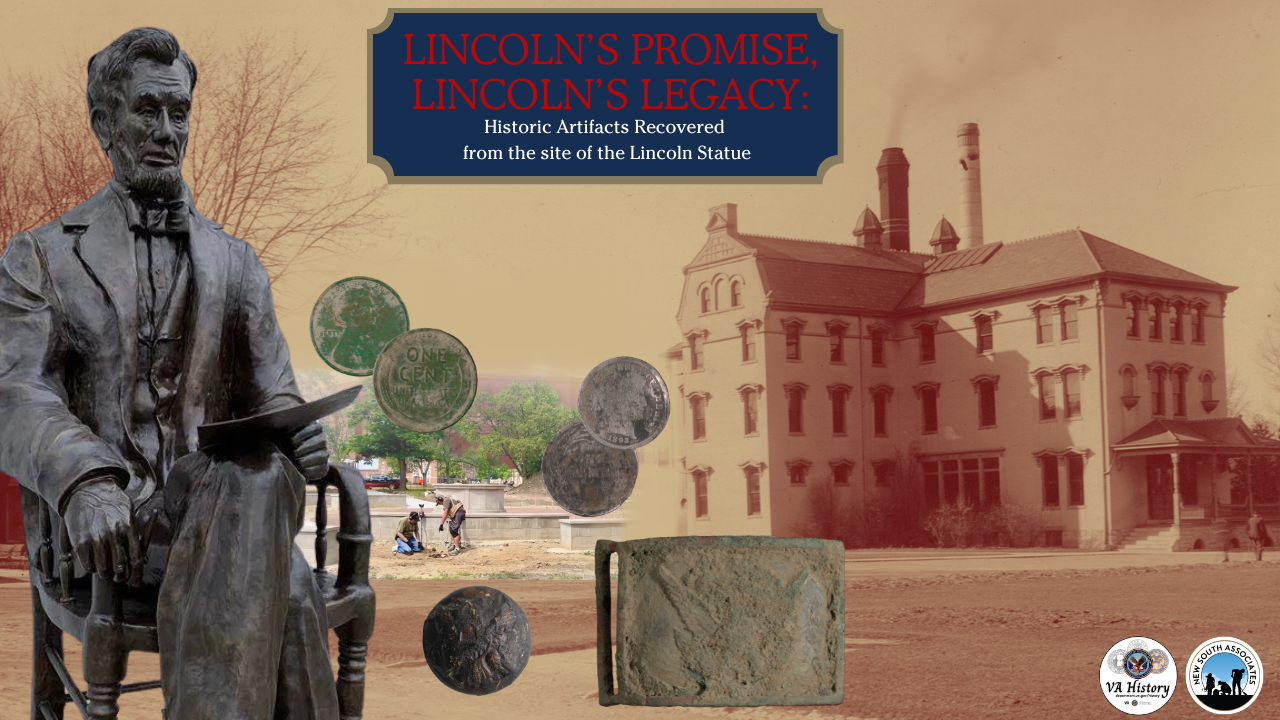

Lincoln’s Promise, Lincoln’s Legacy: Historic Artifacts Recovered from Site of Dayton Statue

It all started when Bill DeFries, President of the American Veteran’s Heritage Center (AVHC), lost his wedding ring at the construction site for the statue of Abraham Lincoln on the campus of the Dayton VA Medical Center. He requested the assistance of the Dayton Diggers, a local nonprofit whose mission is to “research, recover, and document history” through their use of metal detector survey. The machines used by Dayton Diggers emit an electromagnetic field that responds to metal objects hidden below the ground surface. When they pinpoint a target, they use minimally invasive excavation to remove the object from the soil. In addition to the misplaced wedding band, their team uncovered historic artifacts that can be used to understand the history of Veteran care here in Dayton.