After World War I, Americans discharged from military service faced a difficult homecoming. Many struggled to find work in the tight labor market created by a post-war recession. They also felt ill-used. During the war, civilian workers benefited from a booming economy and enjoyed wages that far exceeded their own military pay. In the early 1920s, Veterans took their grievances to Congress. The newly formed American Legion and the more established Veterans of Foreign Wars led the way in lobbying for a one-time cash payment that would compensate Veterans for their missed earnings. In 1924, Congress passed the World War Adjusted Compensation Act, which awarded Veterans interest-bearing certificates with a face value of up to $625. But the law came with an important proviso: the certificates could not be redeemed until 1945.

Even with its deferred payout, the Bonus Act, as the bill was called, satisfied Veterans’ demands for some form of monetary compensation for their service. Their attitudes changed, however, with the onset of the Great Depression. The economic crash sent unemployment rates soaring and caused immense hardship for millions of Americans. Veterans were particularly hard hit by the crisis and they appealed to the government for immediate payment of their bonus certificates to alleviate their financial distress. When the administration of President Herbert Hoover proved recalcitrant, they mobilized for action.

In the summer of 1932, an estimated 20,000 Veterans, many with their families in tow, descended on Washington from all parts of the country to petition Congress for their money. Dubbed the “Bonus Army” or “Bonus Marchers,” they settled in tents, cardboard shanties and wooden shacks in parks and empty buildings in downtown Washington. They also established their main encampment across the Anacostia River on a muddy expanse of land called the Flats. Their daily presence on the steps and grounds of the U.S. Capitol, however, failed to win over Hoover or enough members of Congress. After the Senate on June 17 rejected a bill authorizing payment of the bonuses, many of the marchers went home. But even after Congress adjourned for the season in July, several thousand stayed on to continue their protests at the Capitol building.

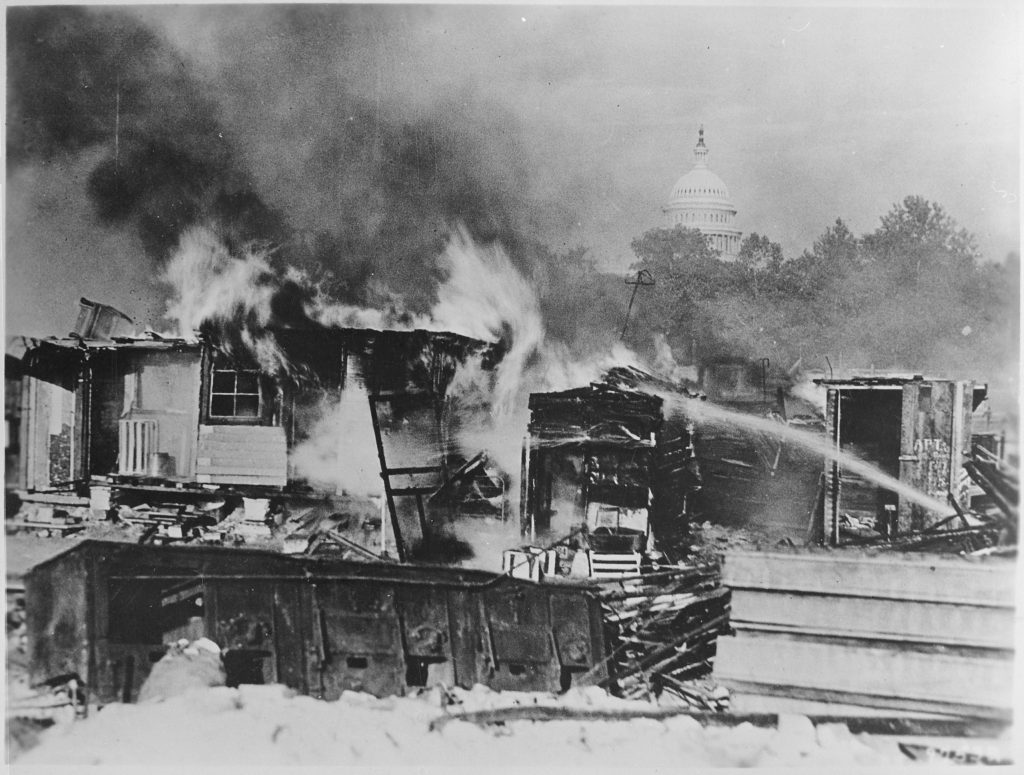

Fearful that the demonstrations would turn violent, Hoover and the District of Columbia Commissioners on July 28 ordered the police to remove the marchers from their downtown camps. Following a skirmish that left two marchers dead and three policemen injured, Hoover made the fateful decision to send in the Army to restore order. Later in the day, six hundred soldiers, some mounted on horseback, and six light tanks under the command of General Douglas MacArthur moved against the Veterans. The troops on foot threw tear gas grenades and the makeshift shantytowns on both sides of the river went up in flames. The Bonus Marchers dispersed and by July 30 the city had been cleared of their presence.

In his official report, MacArthur praised his men for their discipline and avoidance of civilian fatalities. But the events of July 28, splashed across the front pages of the nation’s newspapers and shown in movie theater newsreels for weeks afterwards, prompted a swift backlash. The Army was booed and Hoover excoriated for his heartless treatment of the Bonus Army protesters. When he heard what had happened, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the Democratic candidate for president in 1932, reportedly remarked, “Well, this elects me.” In fact, Roosevelt did handily defeat Hoover in November. His victory left Veterans hopeful that they would soon be able to convert their certificates into money and an estimated 3,000 returned to Washington the following May to press their case. But with the country still in the grips of the Great Depression, Roosevelt had other priorities. Not until 1936 did Congress pass a bill allowing Veterans to exchange their certificates for saving bonds redeemable at any time. The Treasury wound up distributing more than $1.4 billion in payments to needy Veterans that year, as most chose to cash in the bonds within months of receiving them.

By Alexandra Boelhouwer

Virtual Student Federal Service Intern, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 93: Occupational Therapy Floor Loom

During World War I and afterwards, the United States committed to rehabilitating sick and wounded soldiers so they could resume productive lives in the civilian workforce. The emerging field of occupational therapy played a crucial role in the rehabilitative process.