Three burial vaults, two funeral processions a thousand miles apart, and a daytrip to quash an assertion of foul play–the remains of Zachary Taylor, the only U.S. president laid to rest in a VA national cemetery, have taken an especially tortuous path to their resting place in Louisville, Kentucky.

Taylor was a career U.S. Army officer who rose to the rank of major general and became a national hero for his exploits during the Mexican-American War. The Whig Party embraced the apolitical Taylor as their nominee in the 1848 presidential election and his popularity carried him to the White House. But his time in office ended tragically a little more than a year into his presidency. On a sizzling fourth of July in 1850 in the nation’s capital, he attended a ceremony at the unfinished Washington Monument and afterward took refreshment with raw vegetables, cherries, milk, and water. The following day he fell ill with stomach cramps, later diagnosed as cholera, a bacterial infection probably transmitted in the liquids he drank. He died on July 9, 1850, at age 65.

On July 13, Taylor’s elaborate funeral procession, more than a mile long, wound through a capital draped in mourning. The body of the twelfth president lay in a “rich yet simple” metal coffin made by Fisk and Raymond, purportedly with a glass window plate that allowed a view of Taylor’s face. The casket was placed in the public vault at Congressional Cemetery “with no other ceremonies” than a “minister’s simple words and a gun salute,” as one newspaper reported. The vault contained other caskets awaiting burial or relocation, a common practice before refrigeration allowed safe transport of human remains in hot climates.

That fall, Taylor’s unembalmed body began a second, longer journey of around 1,000 miles from Washington, D.C., to a cemetery at the former Taylor farm near Louisville. Departing about October 25, the escorted casket traveled by railroad to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and then along the Ohio River aboard the steamboat Navigator. Upon arrival at the wharf in Louisville on November 1, the casket was lifted onto a hearse and transported to the cemetery in a procession formed by military personnel, city officials, and residents. There, Taylor’s casket was placed in a “modest and unostentatious” vault finished on top and three sides by sod. A bust of the president above the entrance looked out on the half-acre family burial ground. Two years later, his wife, Margaret Mackall Smith Taylor, was placed alongside him when she died.

In the decades after Taylor’s death, the simple, remote burial site came to be seen as inadequate for a president, but public improvements were gradual. In the late 1870s, the Commonwealth of Kentucky funded the building of a monument near the mausoleum. The 30-foot-tall granite shaft, dedicated in 1883, is topped with a life-size statue of Taylor in Carrara marble. The twentieth century saw efforts to federalize the care of Taylor’s remains and transform the site into a “national shrine.” In 1925, Congress authorized the acquisition of the property from Kentucky and ordered the construction of a new mausoleum. The Peter & Burghard Stone Company of Louisville used Indiana limestone to erect the 13-foot-square neoclassical structure, which also features a marble interior and glazed bronze doors. On May 6, 1926, the Taylor caskets were quietly moved into “Verda antique marble sarcophagi” in the new mausoleum. A dedication ceremony was held a few weeks later on Memorial Day.

By 1928, Kentucky had transferred approximately 16.5 acres adjacent to the Taylor burial grounds to the federal government. That year, Congress designated the entire site the Zachary Taylor National Cemetery, although the old vault, mausoleum, and family plots remained the property of his descendants. In 1976, the Society of Colonial Dames XVII Century donated a bronze plaque that was placed on the abandoned vault where he was first interred because they felt “it is rather confusing to the public as to where he is buried.”

Taylor’s resting place endured one final disturbance on June 17, 1991. After a writer maintained that the president may have been poisoned with arsenic, his descendants supported a court order to have the remains tested. The county coroner removed samples of hair, bone, and fingernails for analysis and his casket was then returned to the mausoleum the same day. Within the week, officials determined that Taylor died of natural causes.

By Sara Amy Leach

Senior Historian, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

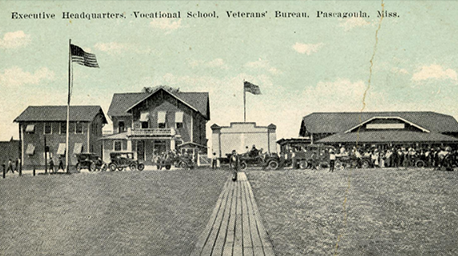

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.