Since Memorial Day was instituted in 1868 (initially as Decoration Day), this event at the end of May became an opportunity to dedicate new monuments in national cemeteries. The installation of figurative or symbolic memorial objects on hallowed ground fulfills a goal articulated the following year by Army Superintendent of National Cemeteries Brevet Major Edmund Whitman: burial grounds were selected with an eye toward “favorable conditions for ornamentation, so that surviving comrades, loving friends, and grateful states, might be encouraged to expend liberally of their means for such purposes.” The placement of monuments (not to be confused with individual grave markers) began to arrive in the 1870s.

At least one hundred of nearly 1,370 monuments at National Cemetery Administration (NCA) properties have been dedicated on or around Memorial Days. While ensuring that military sacrifice and stories of veterans and other dead in VA cemeteries are remembered, the eclecticism of the monuments – materials, size, form, inscriptions – illustrate popular historical designs. These examples also demonstrate how the objects have reconciled living participants at Memorial Day events as much as they honor the dead.

One of the Department of Veteran Affairs’ (VA) oldest Civil War monuments was dedicated May 30, 1873, at a soldiers lot in Forest Hill Cemetery, Wisconsin. The granite Wisconsin Soldier’s Orphans obelisk memorializes eight children from a Madison orphanage, established for offspring of Union soldiers whose parents were killed or were unable to care for them. The children died between 1866 and 1870; individual headstones are inscribed with their initials and the obelisk is inscribed with their full name, date of death and age. The graves of Union soldiers surround the orphan’s monument and graves.

San Francisco National Cemetery, established in 1884 at the Presidio in California, marks the Army’s first national cemetery on the West Coast. The Pacific Coast Garrison Monument was dedicated here in 1897 as part of a Memorial Day program that drew an estimated 10,000 participants and observers. The unveiling, like the telling of it, was dramatic, with “the superb monumental figure…obscured by flags. At the word of command the folds parted and the monument was revealed… At the instant of unveiling[,] guns of the Third Artillery proclaimed the event.” The monument honors the Regular Army & Navy Union, a veterans organization founded in 1886 to support national defense. At more than 17 feet tall, the Union color bearer standing on a base is among the largest of a handful of VA monuments made of cast zinc (“white-bronze”). These are assembled from cast panels joined with solder, screws, and an internal fastening system. Typically unpainted like this one, the zinc oxidizes to a blue-gray color that resembles stone. Such statues were sold through catalogs with different design elements; fifteen figures similar to this one are found in the United States.

Crown Hill National Cemetery, located within a private cemetery of the same name in Indiana, is a relatively small site of Civil War burials. The Women’s Relief Corps No. 44, auxiliary to Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) Post 369, Department of Indiana, erected a limestone monument here to the unknown dead. Carved by Indianapolis stonecutter James F. Needler with an eagle, draped flag, and cannon, its dedication was a special addition to the usual Memorial Day program in 1889. The Indiana Women’s Relief Corps also reported it had placed seventy-one monuments to “unknowns” in the state since the patriotic group organized in 1883.

After the Civil War ended, the federal government was responsible for relocating the graves of hastily buried dead, including Confederate prisoners of war who died at Camp Douglas on south side Chicago. These remains were relocated farther out of the city to a 2-acre lot in Oak Woods Cemetery in 1867. The Ex-Confederate Association of Chicago and United Confederate Veterans Camp No. 8 were allowed to erect a monument there, dedicated on Memorial Day 1895 before a huge crowd. Decoration Day was commemorated by the South and North, often on different dates, before it was federalized in 1968. The Confederate Mound column exceeded 30 feet tall plus an 8-foot bronze of a Confederate soldier. Fifteen years later the monument and immediate site were in poor condition, but the congressionally authorized Commission for Marking Graves of Confederate Dead was responsible for correcting the problems. In a feat of engineering, the monument was lifted to accommodate the installation of a stable foundation finished with polished granite. To this were affixed bronze plaques containing the names of “4275 Confederate soldiers and sailors who died in the prison” and were buried nearby. Like all federal Confederate monuments erected by the commission, inscriptions were “without praise and without censure.” No changes were made to the original monument and work was completed by July 1911.

The Civil War Soldiers Monument at Danville National Cemetery, Illinois, was dedicated on Memorial Day 1917 to the “men who offered their lives in defense of their country.” Ironically the United States entered World War I the month before. The federal government built it as the focal point of a circular-plan cemetery at the Danville Branch-National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (now VA Illiana Health Care System). Each National Home cemetery features a large, singular monument to honor veterans; this one, at Danville, cost $6,000. A plaza surrounds a granite base supporting a life-sized bronze by W. Clark Noble (1858-1938), a sculptor recognized for military monuments and portraits of American statesmen. This figure was used thirteen years earlier for the 100th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Monument installed at Antietam National Battlefield.

The Wisconsin Monument at Marietta National Cemetery, Georgia honors 405 sons of the “badger state” who died in the Battle of Atlanta during the Civil War and are buried nearby. The GAR conceived of the monument and the state legislature approved $5,000 to procure it. The shaft of Wisconsin pink granite inscribed with regimental information is topped, appropriately, by a three-dimensional life-size bronze badger. The Fitzhugh Lee Camp 4, Spanish-American War Veterans, hosted the Memorial Day dedication on May 31, 1926, which included a parade of aging former Union and Confederate soldiers.

World War I German prisoners of war are buried in two VA cemeteries. More than 300 POWs were interned at Fort Douglas, Utah, during the war; twenty-one died of disease and were buried at the Fort Douglas Post Cemetery. They are memorialized by a 15-foot-tall granite-and-bronze Art Moderne monument dedicated May 30, 1933. Donated by German-Americans of the United States and the American Legion of Utah, it was designed and built by converted-Mormon sculptor Arno Alfred Stienicke (1892–1968) with a kneeling figure of a wounded soldier and Bundesadler or “Federal Eagle.” The ceremony included choral music and flowers dropped on the monument from a U.S. Army plane as it flew low over the cemetery.

The 2nd Infantry Division American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) Monument was donated by American Legion Post 850 to Cypress Hills National Cemetery, New York. It is one of few NCA World War I monuments, but its dedication on May 30, 1945, is fitting – just three weeks after Germany’s surrender in World War II. The 2nd Infantry Division lost approximately one-fifth of its force in WWI fighting, especially in France. Perhaps the exigencies of war influenced its appearance, but the bronze plaque affixed to a stone block anticipates the smaller and simpler late twentieth-century memorial objects that veterans groups would donate in volume after most national cemeteries were transferred from the Army to the Veterans Administration in 1973.

An unusual but practical memorial object – a drinking fountain – was dedicated on Memorial Day 1952 at Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery, Missouri. Donated by the 35th Division, St. Louis Reunion Corp, it honors veterans buried here. Its relevance is based on the 35th Division, an infantry formation of the U.S. Army National Guard that dates to 1918, primarily in Kansas and Missouri. President Harry S. Truman was a most-prominent veteran of the 35th Division. Designed by Eugene J. Mackey Jr. (1911-1968), the austere mid-century structure is made of polished pink granite. The site includes a circular swirl of a plaza accessed from a roadway and is framed by a stone wall that serves as seating. More endearing “round” elements include concrete steps and shallow basin large enough for four “bubblers.” The water fountain is an overlooked project within Mackey’s catalog of work. The award-winning architect and Fellow of the American Institute of Architects designed the St. Louis World War II Court of Honor Plaza (1948), Missouri Botanical Garden “Climatron” (1960), and many significant St. Louis buildings. The 35th Division Monument is unique to VA national cemeteries.

Beginning in the late twentieth century, NCA has organized its donated “standard monuments” along memorial pathways to improve the visitors’ experience. Fort Custer and Fort Snelling national cemeteries, Michigan and Minnesota, respectively, each saw ten monuments dedicated on Memorial Days. At Fort Snelling, one of VA’s busiest cemeteries based on number of interments, in 1995 the Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 425 donated five monuments, one for each military service.

As a result of the ongoing response to the COVID-19 pandemic, no new monuments will be dedicated on Memorial Day 2021. However, based on the history of memorialization at VA’s national cemeteries, generous organizations will continue to donate evocative monuments to honor the veterans we have lost and prolong their memory. Brevet Major Edmund Whitman would likely be pleased with the appearance of national cemeteries for this, the nation’s 153rd Memorial Day.

Footnotes

- Memorial Day was observed on May 30 from 1868 to 1970; legislation moved it to the last Monday of the month, as a federal holiday, starting in 1971. 82 Stat. 250 – An Act to provide for uniform annual observances of certain legal public holidays on Mondays, and for other purposes – Content Details – STATUTE-82-Pg250-3. ↩

- Report of Brevt. Lt. Col. E.B. Whitman, Supt. National Cemeteries, Dept. of the Cumberland, Louis Ky., May 10, 1869.” NARA RG 92, Entry 646.. ↩

- 01 Jun 1897, Page 9 – The San Francisco Call. 07 Feb 1897, Page 16 – The San Francisco Call. ↩

- Army & Navy Union-Defenses of Washington Garrison No. 65. ↩

- Confederate Mound Monument assessment/conservation records. NCA History files. ↩

- Crown Hill National Cemetery registration form for historic places (PDF, 24 pages); Woman’s Relief Corps – auxiliary to Grand Army of the Republic; 27 May 1889, Page 4 – The Indianapolis News. ↩

- National Cemetery Administration Federal Stewardship of Confederate Dead (PDF, 342 pages), pps. 34, 77-84. ↩

- 08 Jun 1917, 2 – Sibley Journal . ↩

- W. Clark Noble | Smithsonian American Art Museum. Art Inventories Catalog – Smithsonian Institution Research Information System. 100th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Monument – Antietam National Battlefield, U.S. National Park Service. ↩

- 29 May 1926, 6 – Kenosha News. 01 Jun 1926, 1 – The Atlanta Constitution. ↩

- The 2nd Division A. E. F. — Syllabi. ↩

- 31 May 1952, 11 – St. Louis Globe-Democrat. 31 May 1952, Page 3 – St. Louis Post-Dispatch. ↩

- Thirty-Fifth Division Association Records | Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. ↩

- Obituary, 28 Jul 1968, Page 29 – St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Eugene Joseph Mackey, Jr. Application for Membership to the American Institute of Architects (PDF, 25 pages). ↩

By Sara Amy Leach

Senior Historian, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

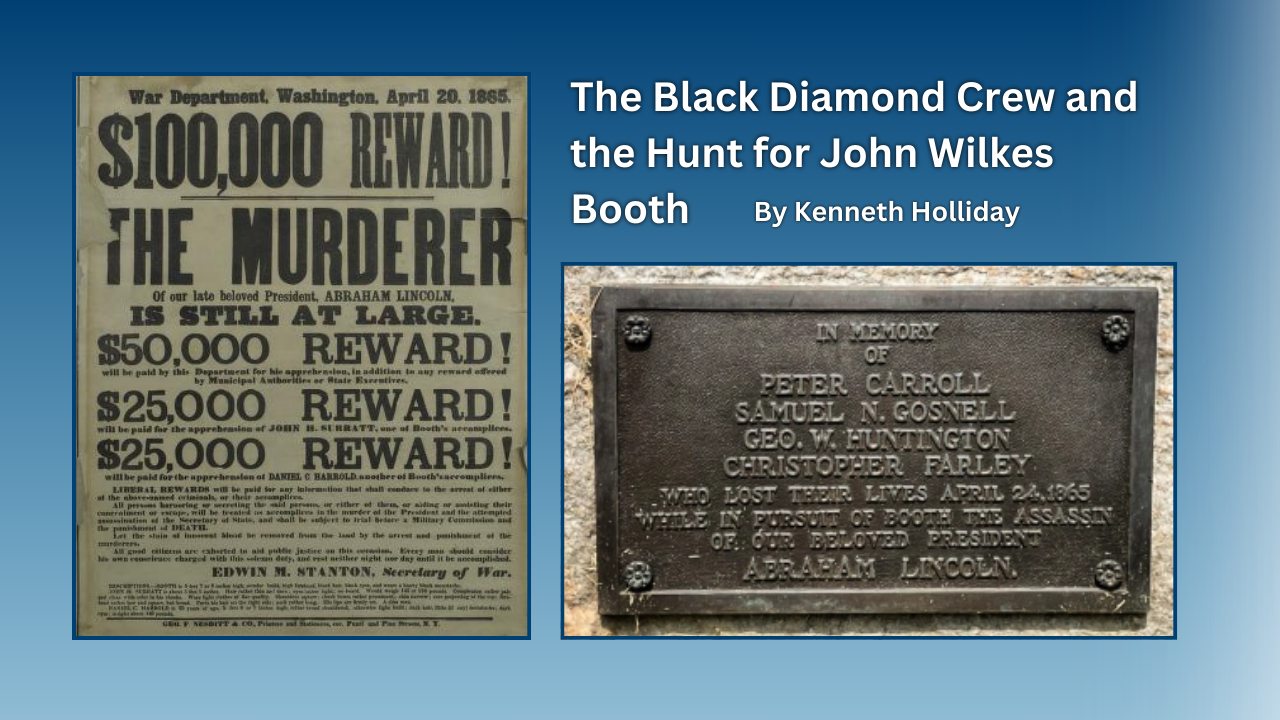

During the late evening, early hours of April 23-24, 1865, the Black Diamond, a ship on the Potomac River searching for President Abraham Lincoln's assassin John Wilkes Booth collided with another ship, the USS Massachusetts. The incident was a terrible accident during the frantic mission to locate the fleeing Booth before he escaped into Virginia. Unfortunately many lives were lost, including four civilians who had been summoned from a local fire department by the Army. For their assistance during this military operation, all four were buried in the Alexandria National Cemetery, some of the few civilians to receive that honor.

Featured Stories

In the mid-twentieth century, the lives of Dr. Ivy Brooks and Mildred Dixon, two trailblazing Black women physicians, converged at the Tuskegee, Alabama, VA Medical Center. Doctor's Ivy Roach Brooks and Mildred Kelly Dixon shared much in common. Both women were born in 1916 in the northeastern United States and received training in East Orange, New Jersey. They both launched careers in alternate medical professions before entering the fields of radiology and podiatry, respectively. Pioneering many “firsts” throughout their professional lives, both women faced and overcame the rampant racism and sexism of the era.

Featured Stories

After the United States entered World War I in 1917, American Expeditionary Force commander General John J. Pershing requested the recruitment of women telephone operators that were bi-lingual in English and French. Eventually 233 were selected out of over 10,000 applicants, and they served honorably through the war, earning the nickname of 'Hello Girls.'

However, their employment was not officially recognized as military service and therefore were neither honorably discharged, or eligible for the benefits other returning Veterans would receive. This kicked off a 60-year fight for 'Hello Girls' to receive legal Veteran status.