As World War II ended and millions of service members returned home, the Veterans Administration faced the major challenge of not just delivering benefits and medical care, but also ensuring broad public awareness of these programs. Congress had passed numerous forms of assistance for Veterans during the war and, in 1946, President Harry S. Truman directed General Omar N. Bradley, the newly appointed VA Administrator, to modernize VA’s delivery of its services.

Confronting the agency was the task of coming up with highly effective ways to communicate benefits information and explain to Veterans how they could take advantage of what they had earned through their military service. Previously, the agency had devoted little effort to disseminating benefits information on a regular, nationwide basis.

Before and during the war years, no other medium had been more influential in keeping the American public informed than radio. In addition to extensive news coverage, many radio broadcasts brought entertainment and tributes to troops around the world and those on the home front. To VA, radio seemed a surefire way to reach a mass audience of Veterans with important information about benefits and services. However, to gain maximum exposure and hold the listener’s interest, the approach had to be novel and unique enough to rise above common everyday public service messaging.

The VA Public Relations office in Washington took on that challenge. Its director of Radio Service at the time was Joseph L. Brechner, a savvy broadcast executive who had brought his talents to the agency after the war. Using his industry connections, Brechner took an innovative path involving the cooperation of the Advertising Council, the American Federation of Radio Artists, and the national radio networks.

He decided to produce weekly 15-minute programs that carried VA’s public service messages within what were mini versions of some of America’s most popular radio shows. Each broadcast would be high quality and custom-made for broad audience appeal and to convince stations across the country to place it on their schedules. And, so, Here’s To Veterans was born. The first series of programs premiered in mid-1946 with distribution to nearly a thousand stations on 16-inch vinyl discs, known as transcriptions.

For the first several years, the program featured giants of the entertainment industry, including Milton Berle, Fibber McGee & Molly, Jack Benny, and Dinah Shore. It quickly became one of the most successful public information campaigns ever undertaken by a federal agency. The unique content of each show boasting the participation of so many well-known popular entertainers also marked it as a signal moment in radio history.

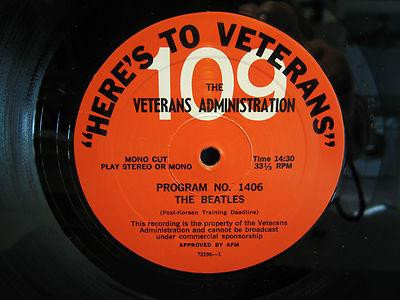

The life of Here’s To Veterans as an agency public information vehicle did not end even after its postwar mission had been largely achieved. In the 1950s, it transitioned into a program with much the same format, but now devoted entirely to popular music featuring well-known recording artists.

Under a special arrangement with the American Federation of Musicians and Capitol Records, stars like Nat “King” Cole, Jo Stafford, Stan Kenton, and Les Paul not only performed some of their latest releases, but also served as the hosts, voicing VA benefits messages. Now aimed at reaching Veterans of the Korean and Vietnam Wars, Here’s To Veterans provided a way for radio stations to present an entertaining program coupled with public service information for their listeners.

For a brief period in the late 1970s, VA reissued a series of its original programs with fresh message content, capitalizing on an industry trend at the time—broadcasts from the “Golden Age of Radio.” Finally, in 1981, the last pressings of Here’s To Veterans were released as the agency shifted to more contemporary means of disseminating public service messages on radio and television.

Today, the complete 35-year series with over 1,800 programs are housed at the National Archives. Copies that survive are avidly sought by collectors, and downloads can be accessed on internet sites specializing in programs from radio’s most memorable era. In that sense, the program lives on, illustrating its success as a highly effective and creative means of outreach to the Veteran population.

By Donald R. Smith

Associate Deputy Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs (Retired)

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.