In October 1918, in the waning days of World War I, the French warships Marseillaise, Gloire, and Montcalm arrived at the port of New York. Later that month, sailors from these vessels marched in a Liberty Loan Parade to promote the sale of war bonds. The timing of the patriotic display proved extremely ill-advised.

A second wave of the influenza pandemic had already reached American shores. A similar event staged in the streets of Philadelphia the previous month led to outbreak of the disease that sickened an estimated 75,000 people within weeks. In New York, many spectators and participants in the parade also contracted influenza. By the time the second wave had run its course in mid-November, 21,000 New Yorkers had died from influenza or pneumonia.

The French sailors who fell ill were sent to the U.S. Naval Hospital on Brooklyn Navy Yard for treatment. Twenty-five of them died between October 1918 and January 1919. U.S. officials arranged for their burial in an unused section of Cypress Hills National Cemetery in Brooklyn. Their graves were marked by black wooden crosses with bronze name plates.

Dedication of the French plot took place on November 2, 1918. Rear Admiral Nathaniel R. Usher of the Brooklyn Navy Yard along with admirals of the French and American fleets and other high-ranking military officials attended the military mass for the deceased. Additional graveside ceremonies were conducted on Bastille Day and Armistice Day in 1919 and then again in 1920. A 12-foot granite cross monument was dedicated at the site on the second Armistice Day commemoration. The monument was built by the well-known New York City memorial design firm of Farrington, Gould, and Hoagland. In 1928, the remains of four of the sailors were returned to France for burial, leaving twenty-one in the cemetery’s “French Section.”

Initially, burial of “friendly” foreign nationals was done as a military courtesy. As a result of the U.S. experience in World War I, the Army updated its regulations in May 1933 to formalize burials of allied foreign nationals in national cemeteries:

In time of national emergency, the remains of officers and enlisted men of the armed forces of other countries who die within the continental limits of the United States while serving as instructors or students with the armed forces of the United States may be buried in any post cemetery or post section of any national cemetery without expense to the United States other than for opening, closing, and marking of the grave.

A few months later, this language was revised again to include military personnel of other countries who died while engaged in promoting national defense in the United States. This change encompassed the burial of the French sailors.

In 1920, Congress also passed a special act granting burial privileges in national cemeteries to U.S. citizens “who served in the Army or Navy of any government at war with Germany or Austria.” They qualified for interment “free of cost” if they died in service or received an honorable discharge after completing their enlistment. This law applied to the many thousands of Americans who joined the Allied armed forces prior to the U.S. declaration of war on April 6, 1917.

They volunteered to fight before the United States entered the conflict for a variety of reasons, ranging from youthful idealism or their belief in the Allied cause to a desire for escape, adventure, and military glory. An estimated 40,000 Americans enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Forces. Hundreds more volunteered for service in the British Royal Army and Navy and the French Foreign Legion. A large contingent also served as pilots in British and French flying squadrons. Over 450 saw action in the Royal Flying Corps, Royal Naval Air Service, and Royal Air Force. Another 250 or more flew in French squadrons, including 38 in the Escadrille Américaine, the famed unit comprised almost entirely of American volunteer pilots.

Herman L. Chatkoff was one of the Americans who benefited from the 1920 law. He enlisted in the French Foreign Legion at the start of the war and spent more than a year in the trenches on the Western Front. He lived through the mass slaughter during the first months of the Verdun campaign in 1916 and later the same year entered training to become a pilot in the French Air Service. He went on to earn a Croix de Guerre for his bravery in aerial combat during a series of missions in May and June 1917.

After the United States joined the conflict, many American aviators transferred from the French to the American flying service, but Chatkoff never had that opportunity. On June 15, he crashed his two-seater aircraft, killing his companion in the plane. Chatkoff survived the accident but the injuries he suffered ended his flying career and left him permanently disabled. In 1931, Congress approved a private law awarding him the same compensation and medical care as other Great War Veterans. He died in 1964 and was laid to rest in Baltimore National Ceremony in Maryland.

By National Cemetery Administration History Program

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

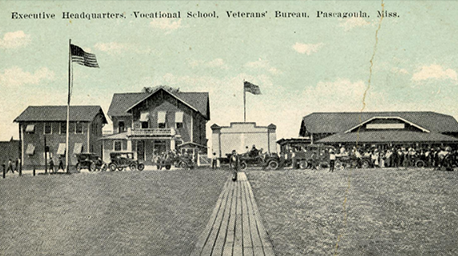

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.