Payments to Union Veterans and their dependents exceeded $5 billion after the Civil War due to the increasingly generous pension laws passed by Congress between 1865 and 1915. But ex-soldiers and their families were not the only beneficiaries of the federal government’s largesse. The expansion of the Civil War pension system was also a cash windfall for the pension attorneys who assisted Veterans with their claims.

What started out as a cottage industry turned into a lucrative business for pension attorneys in the decades following the war. The most successful amassed thousands of clients and collected hundreds of thousands of dollars in fees for their services. They also became a lightning rod for criticism as government spending on pensions climbed higher and higher. Politicians and the press condemned them as sharks and blamed them for many of the ills of the pension system. They were accused of being equal opportunity offenders, bilking Veterans with excessive fees on the one hand and defrauding the government through inflated or false claims on the other.

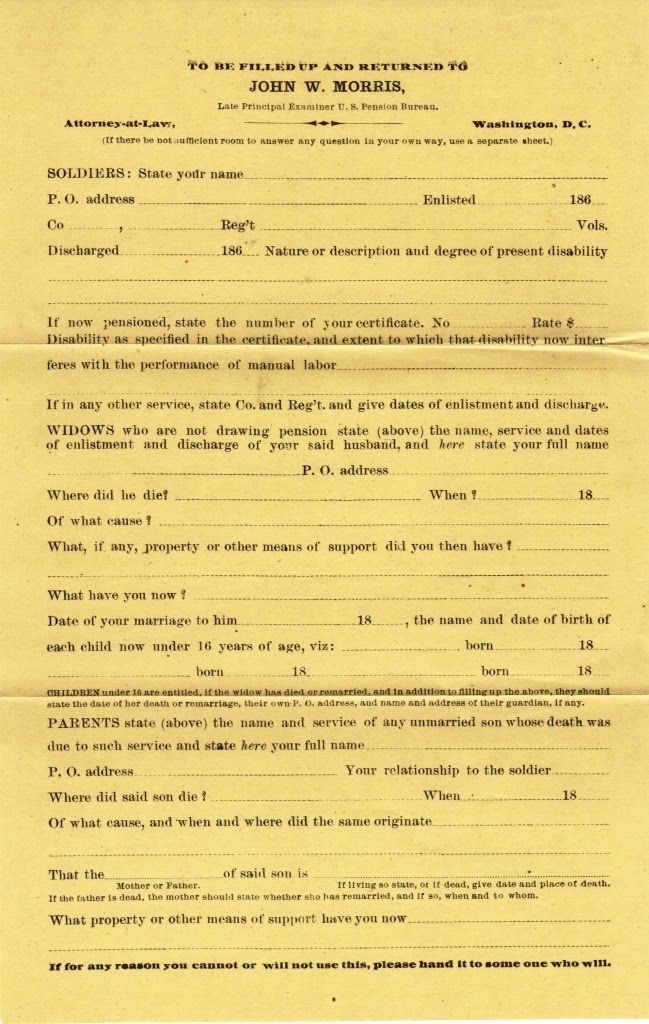

Before 1861, Veterans hired lawyers on occasion to represent them, but their use only became commonplace during the Civil War and afterwards. A study that sampled of over 100,000 pension applications between the years 1862 and 1906 found that over 70 percent were submitted with the aid of an attorney. Pension attorneys used their legal know-how to guide clients through the complex process of applying for benefits. They helped complete the required paperwork and assemble the necessary documentation to substantiate a claim, including the collection of sworn affidavits from witnesses. They also handled all correspondence with the Pension Bureau in Washington, D.C. and interceded on their client’s behalf when needed.

Congress set the fees pension attorneys received for their services and also prescribed the penalties for their misconduct. An 1870 law increased the amount they could charge from $10 to a maximum of $25 but only if they submitted a signed contract specifying the agreed upon fee to the Pension Bureau. In the absence of a contract, the default rate remained $10. In all cases, attorneys were only entitled to collect payment for applications that were approved by the Pension Bureau. Congress probably included this stipulation to discourage the filing of dubious or frivolous claims but it had the opposite effect, encouraging attorneys to embellish the evidence to ensure they got paid for their work.

The Pension Bureau maintained a roster of attorneys who were authorized to practice before the agency. By the end of the century, the number of names on the list approached 50,000. The majority of lawyers handled a small number of cases and served Veterans residing in their locality. But some attorneys saw the potential for marketing their legal services on a national scale. They sent out promotional materials through the mail to advertise their credentials and drum up business. The more enterprising attorneys also built up their practice by hiring teams of claims agents to scour the countryside in search of prospective clients. Agents did the legwork, finding claimants, identifying witnesses and collecting their testimony, and then submitting the whole package under the attorney’s name to the Pension Bureau.

Through the deployment of agents, a handful of attorneys were able to capture an enormous share of the pension market. In 1880, the Commissioner of Pensions testified to Congress that the ten largest firms represented over 100,000 of the claims currently pending with the bureau. Most maintained offices in Washington, D.C., which offered the lawyers easy access to both officials in the Pension Bureau and power brokers in Congress.

George E. Lemon was the most successful of the Washington-based pension attorneys. Lemon was a Union Veteran himself who had been wounded during the war. He set up shop in Washington in 1865 and over the next 15 years prosecuted, in his own estimate, at least 50,000 claims if not “considerably more than that.” In 1877, he launched The National Tribune, a monthly newspaper “devoted to the interests of the Soldiers and Sailors of the late war, and all Pensioners of the United States.” Lemon was not the only pension attorney to branch out into the newspaper business, but his attracted the largest readership, going out to over 112,000 paid subscribers by 1884. He used its pages to advocate for increasing benefits and expanding eligibility while also promoting his own agency. “CLAIMS! CLAIMS!” read the ad that filled the back page.

Lemon and the other leading pension attorneys often made common cause with the Grand Army of the Republic, the fraternal organization for Union Veterans that became a powerful lobby for pensions in the 1880s and later decades. But they were on far less friendly terms with Pension Bureau, which policed their activities. Special examiners at the agency investigated attorneys accused of wrongdoing such as overcharging claimants, forging papers, or falsifying evidence. Attorneys who violated the law could be fined or, in extreme cases, imprisoned and sentenced to up to two years of hard labor. But the far more common punishment was disbarment or being prohibited from doing business with the Pension Bureau.

Despite their best efforts to weed out fraud, Pension Bureau officials recognized that many transgressions went undetected. The pension commissioner, in his 1894 annual report, lamented that some pension agents and claims agents “are the most dishonest and unscrupulous of men, dealing habitually in perjury, forgery, and every species of fraud and falsehood.” Many in Congress and the press agreed with this characterization. “Pension shark” was the epithet frequently used by newspaper and magazine writers, who viewed the lawyers as both predators and parasites. An 1899 article in the New York Times titled “Methods of the Pension Shark” observed that “no profession in the past has yielded in so short a time so much money for so little brains.”

Calls for reforming their conduct went unheeded but the demand for pension attorneys dropped off sharply after 1906 anyway. By this date, almost all persons eligible to receive a pension had already been granted one. Their fortunes continued to decline after World War I. Veteran service organizations supplanted the attorneys by providing the same services to Veterans free of charge.

In recent years, “claims sharks” have resurfaced in the form of unaccredited agencies offering to help Veterans file PACT Act claims—for a fee. To learn more about fraud protection, visit the VA website here.

By Jeffrey Seiken, PhD, Historian

Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.