Preserving medical innovation artifacts

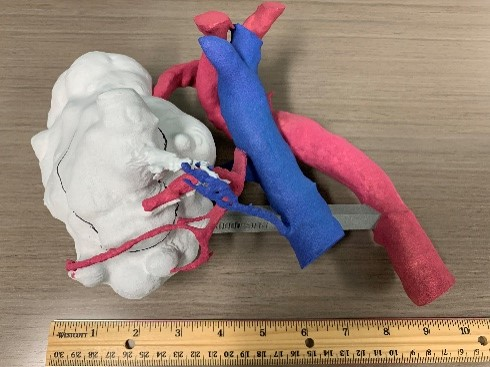

In early 2019, the Seattle VA Medical Center (VAMC) made a breakthrough. A pending surgical procedure called for the removal of a tumor from a Veteran patient’s kidney. Complicating the matter, the patient had a unique congenital configuration of veins and arteries in their kidney. The surgical team needed to assess the best approach for the removal of the tumor. Rehearsing surgery isn’t a new concept; teams review imaging as a routine matter. The innovation in this particular collaboration involved the surgical team, medical imagery, and a new partner – 3D printing technology.

The idea of creating a 3D printed version of the kidney using the Medical Center’s 3D printing technology and the medical imaging of the tumor proved to be a breakthrough. Examining a 3D version of the tumor in advance resulted in a successful removal, a significant reduction of time on the operating table, and a lower risk for the patient.

“The result is a near-perfect replica of the patient’s anatomy which the surgeon or patient can hold in their hands and inspect from all angles,” said Dr. Beth Ann Ripley, Deputy Chief Officer, Diagnostic Imaging Services, Seattle VAMC, in a February 2019 interview.

The tumor procedure resonated with the National VA History Center (NVAHC) team as one example of the numerous medical and surgical innovations pioneered by the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). These breakthroughs run the gamut, from the cardiac pacemaker, to the first successful liver transplant, and have far-reaching impacts for Veterans and the world. Unfortunately, the artifacts related to them are often lost or discarded, a consequences of VA’s lack of an overarching history program.

The 3D tumor came to the attention of the NVAHC team in early 2021. The former Acting Undersecretary of Health, Dr. Richard Stone, had mentioned the innovation in several presentations and it was noted in news stories. Our next question? Who had that 3D tumor and how do we get it?

Typically, historic artifacts are decades (if not centuries) old. For the emerging NVAHC, our focus also includes awareness of contemporary objects that represent unique changes or innovations in VA that are likely to be of notable historical significance in the future.

A recent example of collecting and preserving contemporary items for future researchers has been the COVID pandemic. VAHO has collected a range of documents, images, oral history interviews, and artifacts related to VA and this national emergency.

The challenge to curators and archivists in collecting contemporary items is not simply what to collect, but when and how to collect them. In the rush of daily operations, items that might be of interest are disposed of or kept as local curiosities. Other items may still be needed as part of ongoing business and cannot realistically be surrendered to the historical collection (think of a ventilator modified for use early in the COVID crisis which are still needed in VA hospitals).

When it came to locating the 3D tumor, did the surgeons and technicians still have it? Collaborating with our VHA Historian, Katie Delacenserie, we started at the top. The VHA Chief of Staff, Jon Jensen, an avid supporter of the VA History initiative, was eager to highlight the untold story of VHA research. The conversation was simple, and the kind historians wish for when seeking leadership support:

VA Chief Historian: “We need this for the collection.”

VHA Chief of Staff: “We’ll get it.”

On June 4, 2021, Jensen put out the word to locate the model. He also put us in touch with several VHA contacts familiar with the procedure, notably Dr. Ryan Vega, VHA Chief of Healthcare Innovation and Learning, and Dr. Ripley, at the Seattle VAMC. These contacts would allow us to document its provenance – the background information essential to any artifact we are preserving.

By September 3, 2021, the 3D tumor was in the hands of VA historians and shortly after, forwarded to Curator Kurt Senn and safely stored at our temporary storage site in Dayton, Ohio. The tumor adds to our collection of VA medical innovations, and the search for it, to our knowledge of how to obtain key artifacts for preservation.

By Michael Visconage

Chief Historian, Department of Veterans Affairs

Share this story

Related Stories

Curator Corner

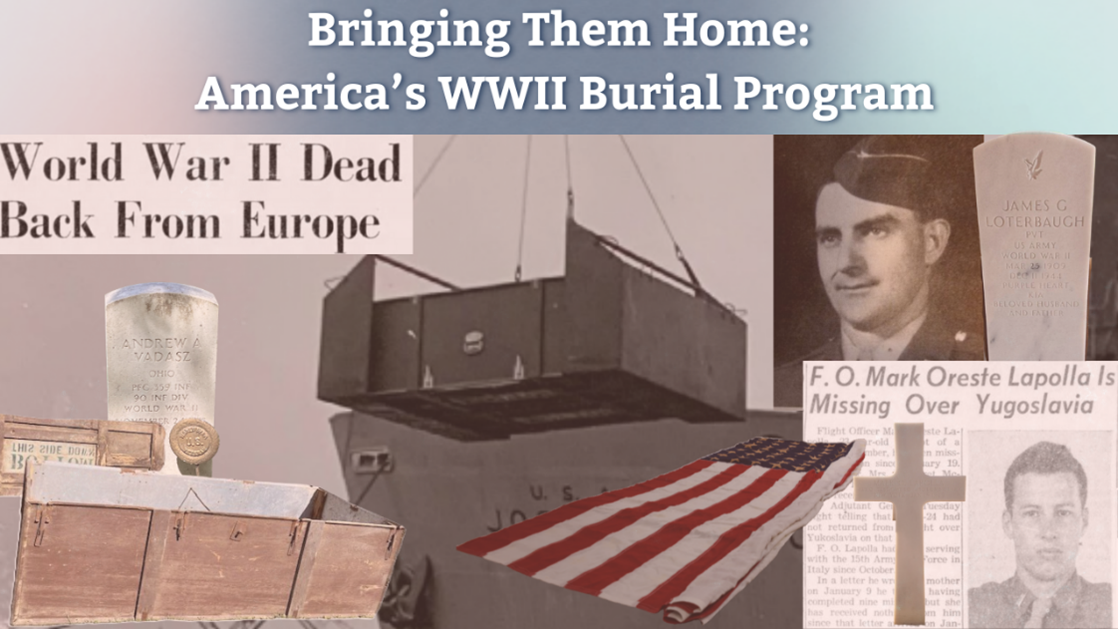

Bringing them Home: America’s WWII Burial Program

VA History is defined by public service to those who have fought for this country. For nearly 250 years, Americans have responded to the challenges Veterans face in innovative ways. But what happens for those who do not return home? This is the story of three Americans who paid the ultimate sacrifice fighting fascism in Europe, how each one was honored after death, and how the VA History Office is preserving their story.

Curator Corner

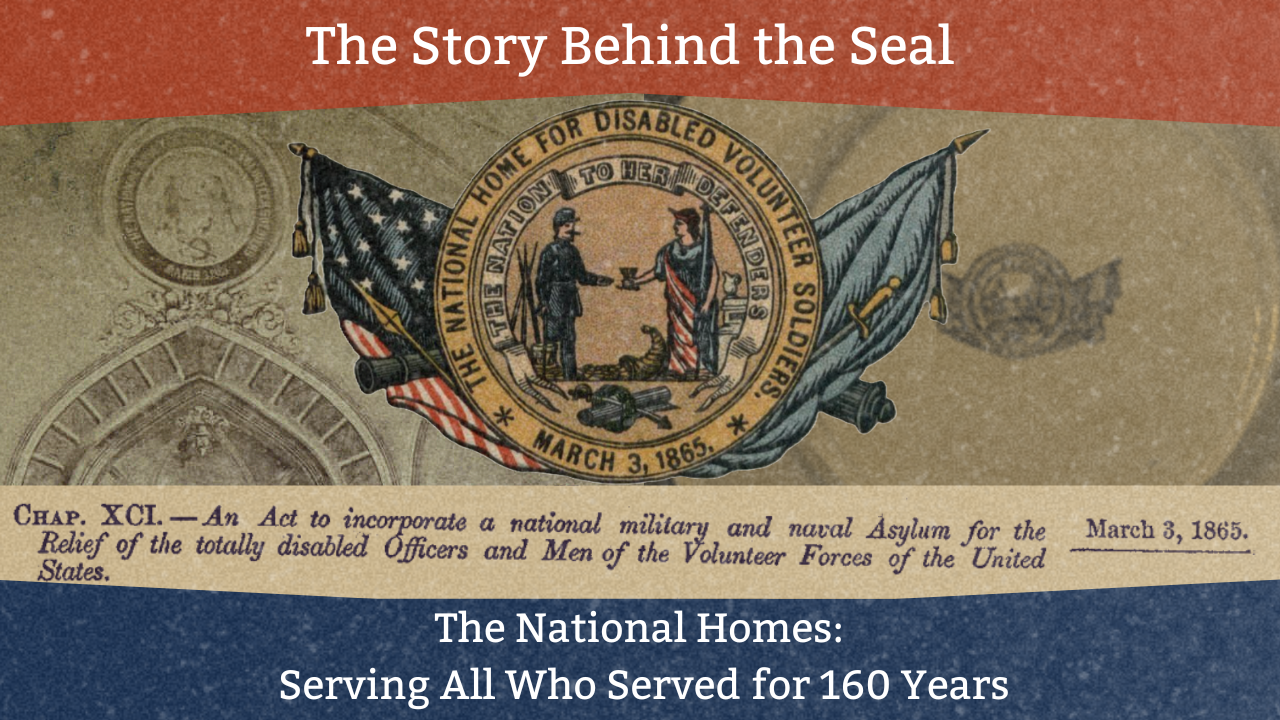

The Story Behind the National Homes’ Seal

The National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers turns 160 years old in 2025. The campuses are the oldest in the VA system, providing healthcare to Veterans to this day.

At the time of their establishment, they were the first of their type on this scale in the world. Within the NHDVS seal is the story that goes back 160 years ago.