A flood hits the VA’s history collection

Picture it: Dayton, Ohio, two days after Christmas 2022. During that week, the temperature hovered between -9 and 10 above. I’m just back from the barn, ensuring the horses are well blanketed and the heated water buckets are doing their job. Despite being on leave, my work phone was on the table, and I just had to sneak a peek. The iMessage banner doesn’t bother me, figuring that it’s a happy holidays text. Not exactly, it’s Dayton VA Medical Center’s (VAMC) Chief Engineer who is a long-time History Center supporter. “Can you please call me?”

This is not a regular ask, so I called her immediately. It went to voicemail, but she called me back straight away, and I could tell she’d been running. She and I have a well-established pattern of talking about our dogs first (shoutout to Paco!) and then getting on to the day’s business. That didn’t happen this time; her words made my blood colder than the barn had been. “A pipe burst in 401.” I ignored the fact I was in cold weather bibs, had hay in random places, and was not terribly clean. I said, “I’m on my way.” She gave me a better picture of what had happened, and to be honest, the next several days were a bit of a blur for many of us, including Engineering, Logistics, Environmental Management, and Contracting.

The burst pipe was on the first floor, and the collections were on the third floor. (Yes, I could have led with that, but it wouldn’t have been nearly as good a journey to take you on!) However, the reception area, the conference room, the curator’s office, and one section of the receiving room were decimated. The elevator to the third floor is in the middle of this same space, as well. The result was that the entire area was unsafe for us or the collections, and we had to move everything to the third floor as the first floor was now a construction zone. To make matters more interesting, by December 30, it was up to 61 degrees, meaning mold was now a very valid strategic concern. We spent several months figuring out remediation, including how we were going to continue to work, the impact on everyone even remotely involved, the financial implications, and what the long-term picture was going to be.

After a great deal of time, effort, and energy from many people, we moved from Building 401 to Building 126 in May 2023. This building change was previously discussed with VAMC leadership, but the pipe burst increased our urgency to find a new home.

It was a challenging way to start 2023. As we just observed the first anniversary, we are grateful to have been invited to make our home on the Dayton VAMC campus. The building is safe, the collections are safe, and so are we. Furthermore, we can thrive. With that, it’s time to go to the barn.

Look for more on our move to building 126 in “We’re Moving on Up” in our next post.

By Robyn Rodgers

Senior Archivist, National VA History Center

Share this story

Related Stories

Curator Corner

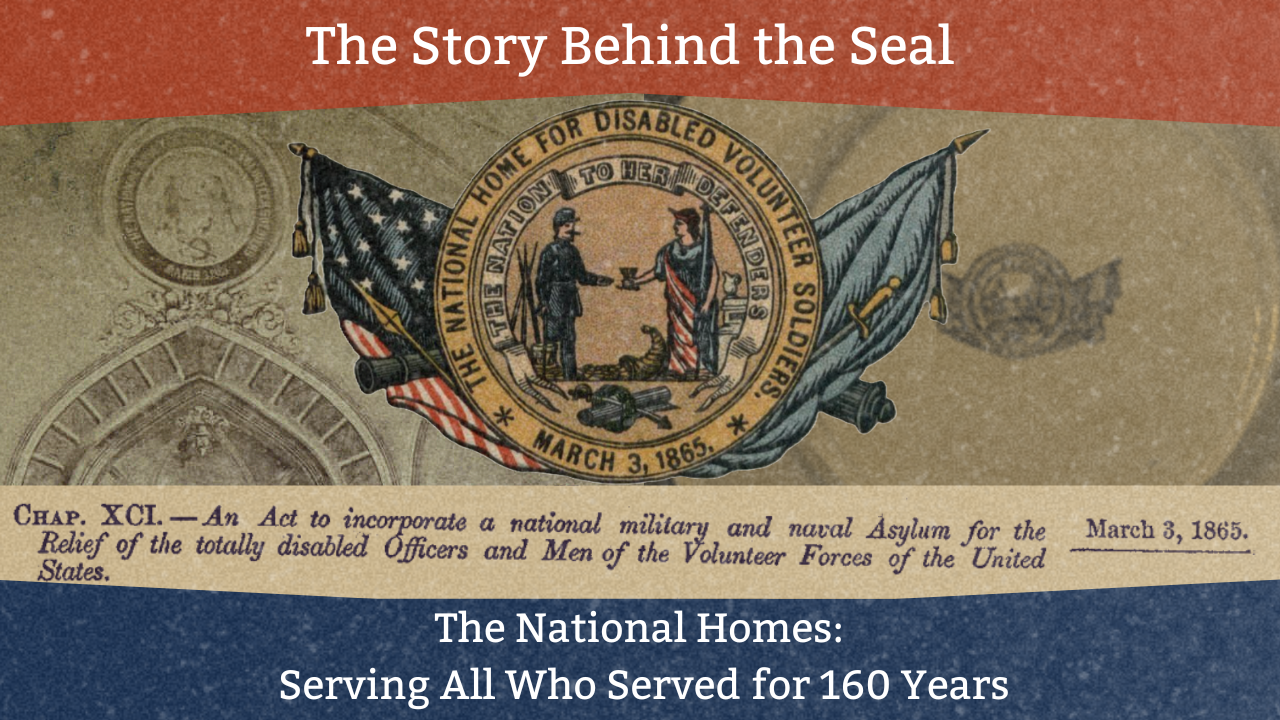

The Story Behind the National Homes’ Seal

The National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers turns 160 years old in 2025. The campuses are the oldest in the VA system, providing healthcare to Veterans to this day.

At the time of their establishment, they were the first of their type on this scale in the world. Within the NHDVS seal is the story that goes back 160 years ago.

Curator Corner

What’s in the Box? Fire Safety and Prevention at the National Homes

Fire safety may not be the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about Veteran care, but during the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers period (1865-1930), it was a critical concern. With campuses largely constructed of wooden-frame buildings, housing thousands of often elderly and disabled Veterans, the risk of fire was ever-present. Leaders of the National Homes were keenly aware of this danger, as reflected in their efforts to establish early fire safety protocols.

Throughout the late 19th century, the National Homes developed fire departments that were often staffed by Veteran residents, and the Central Branch in Dayton even had a steam fire engine. Maps from this era, produced by the Sanborn Map Company for fire insurance purposes, reveal detailed records of fire prevention equipment and strategies used at the Homes. These records provide us with a rare glimpse into evolving fire safety measures in the late 19th and early 20th Century, all part of a collective effort to ensure the well-being of the many Veterans living there.