As the reality of a global pandemic set in, historians, archivists and museum professionals recognized the need to participate in contemporary collecting and actively sought “artifacts” to tell the story of the coronavirus. The newly established VA History Office (VAHO) was no exception. As the VA released their COVID-19 Response Plan in March 2020, VAHO developed their own plan to collect materials that illustrated the response and house them at the National VA History Center (NVAHC). With only a skeleton crew, VAHO reached out to VA employees, asking them to send resources and objects that told their stories.

By the summer of 2021, the VA Central Office, 36 medical centers, and three national cemeteries generated over 350 submissions for the collection. Through a SharePoint site, the community provided VAHO with a multitude of documents, correspondence, photos, videos and objects. This contemporary collection helps to capture materials that tend to be lost with time. Personal accounts and ephemeral objects that are typically forgotten will humanize a significant period in history before the memories fade and pieces are thrown away or stuck in storage. Rather than historians reconstructing what happened, providers who live the challenges everyday can contextualize the subtle responses and changes during the pandemic. However, contemporary collecting also offers unique challenges. Materials like ventilators, training equipment, and signs are still being utilized in the fight against COVID and will be for quite some time. At this point, these are only potential donations to the collection.

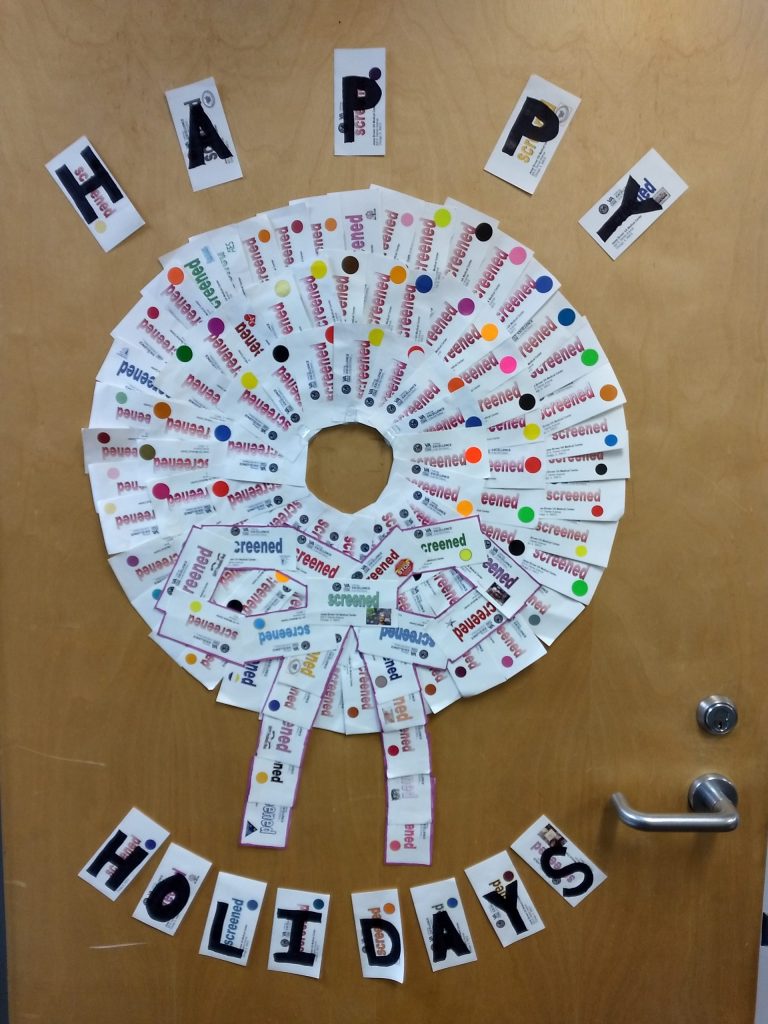

One unexpected narrative emerging from the COVID-19 submissions is the creativity within the community. VA employees showed themselves to be poets, musicians, artists, and seamstresses utilizing their skills to support veterans and their fellow co-workers. When manufactured face masks were scarce, homemade ones of various types protected employees and veterans alike. Screening wrist bands in Palo Alto took new life as a paper chain, meant to bring cheer as Christmas decorations. The VA Greater Los Angeles nurses posted “COVIDian Rhapsody” to Facebook, a lip-sync parody of Queen’s famous song, in celebration of Nurse’s Week. With a little humor, the video addresses issues of the pandemic and shows support for frontline workers.

Creativity also proved useful in the problem solving needed for facilities to continue functioning safely through the pandemic. Submissions illustrating innovative responses arise. Clement J. Zablocki VA Medical Center in Milwaukee fabricated a shield to protect the provider during intubation of a patient. Riverside National Cemetery utilized their herbicide sprayer to disinfect commonly touched surfaces as they dealt with a surge in burials. Multiple facilities collaborated with outside affiliations harnessing 3-D printing capabilities to manufacture a new supply chain for resources.

Digital information encompasses the largest portion of the submitted materials. Correspondence, newsletters, PowerPoint presentations, training documents, and memos furnish potential researchers with an insider’s look at how fast the information changed. Videos and photos express outreach and moral support for Veterans and fellow providers. Objects received by NVAHC currently consist of items like masks, face shields, and 3-D printed swabs showing the early days of supply shortages. Other materials grant a glimpse into the social changes occurring in facilities. A prayer jar in the Atlanta Medical Center allowed for a socially distanced connection between the Chaplain and those in need. Coloring sheets hung in the break room of the Dayton Medical Center offered a moment to de-stress for nurses and other staff.

The pandemic has shown it is not finished and neither is VAHO. In fact, the work is just starting. Donations trickle in and particular materials are still needed to address aspects of the pandemic. Digital files of various directional and procedural signs have been submitted but the physical signage is also needed. Traffic pattern flows and photos of makeshift isolation rooms would aid in addressing the early surge of patients to the medical facilities. Documentation of changing procedures in regional benefit offices would help ensure that story is told. Photos and other documentation of the changes that affected cemeteries is necessary. VAHO continues to take submissions and collect materials associated with the coronavirus pandemic. This collection will not only honor the response and experiences of the VA community, but also provide education to future generations.

By Amy Ackman

Graduate Intern, Wright State University

Share this story

Related Stories

Curator Corner

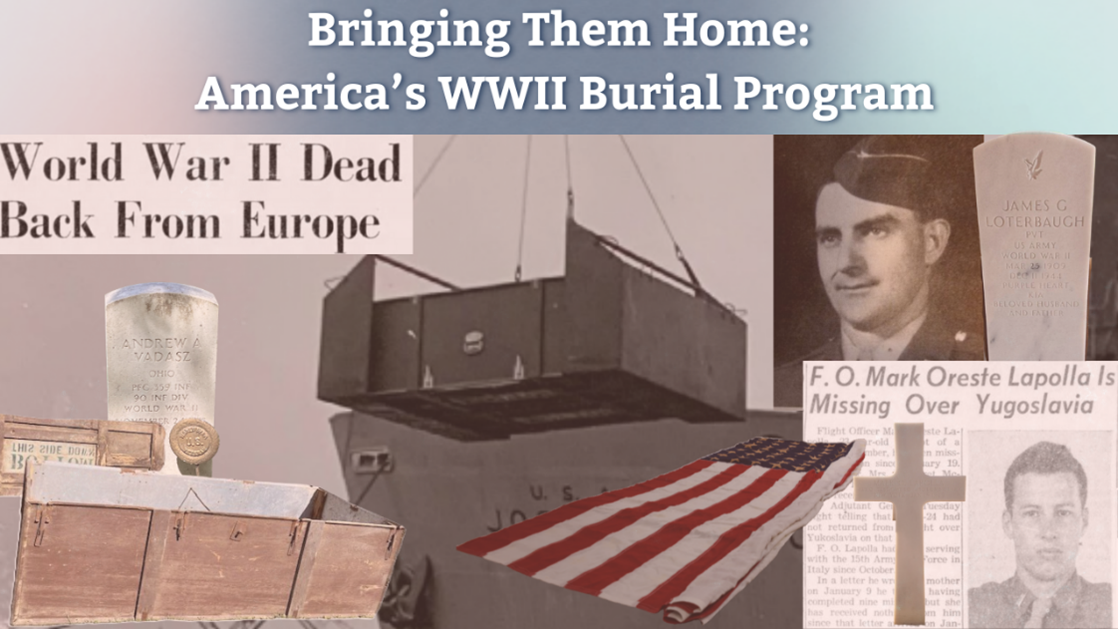

Bringing them Home: America’s WWII Burial Program

VA History is defined by public service to those who have fought for this country. For nearly 250 years, Americans have responded to the challenges Veterans face in innovative ways. But what happens for those who do not return home? This is the story of three Americans who paid the ultimate sacrifice fighting fascism in Europe, how each one was honored after death, and how the VA History Office is preserving their story.

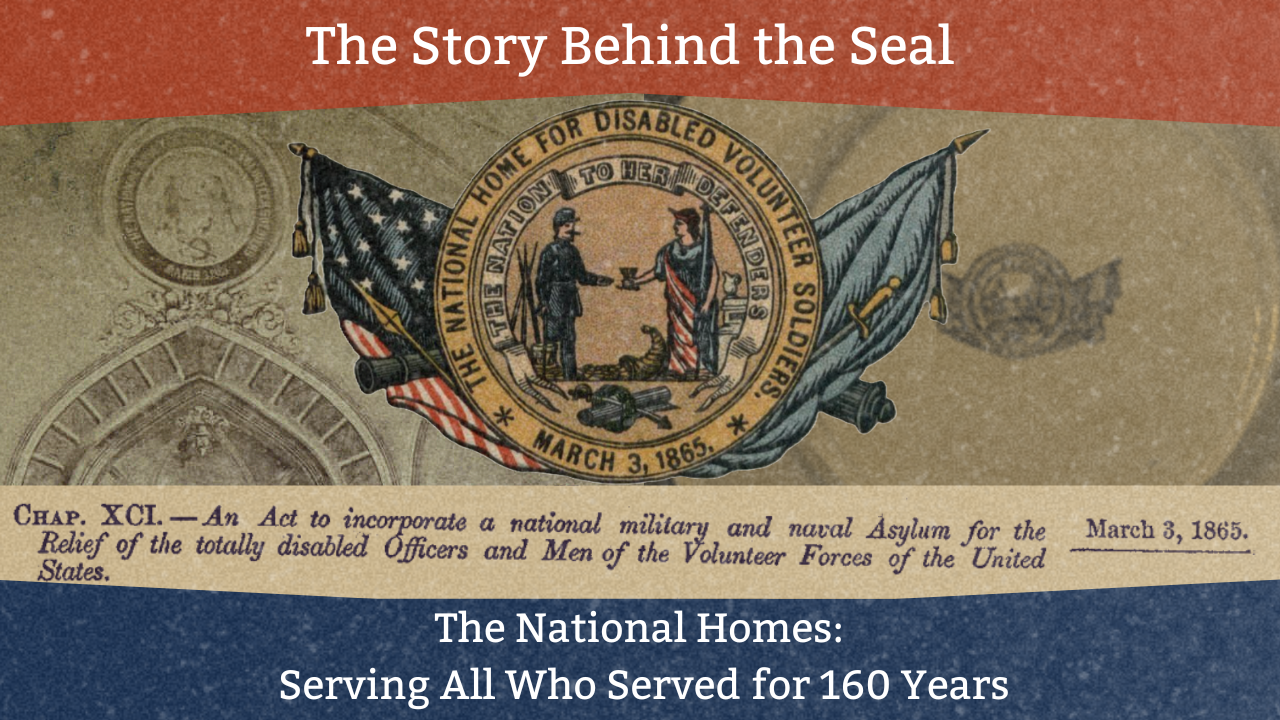

Curator Corner

The Story Behind the National Homes’ Seal

The National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers turns 160 years old in 2025. The campuses are the oldest in the VA system, providing healthcare to Veterans to this day.

At the time of their establishment, they were the first of their type on this scale in the world. Within the NHDVS seal is the story that goes back 160 years ago.