On July 28, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6230 creating the Board of Veterans’ Appeals. The Board was created as part of the Veterans Administration (VA), which had been established only three years earlier. Many Veterans found themselves out of work during the Great Depression and they sought a reevaluation of their benefits claims to alleviate their financial distress. The Board thus allowed Veterans with disabilities to request a second hearing on their claims in the hopes of receiving a fairer and more generous decision. [1]

It took roughly five months after Roosevelt’s executive order to get the Board up and running, as the president needed to select both the chairman and other members of the Board. During this interim period, Veterans seeking an appeal could go to specially created civilian review boards, each of which operated on a local level. About 103 special review boards were in operation by October 1933. Six out of every ten Veterans had their appeals rejected by these local boards.[2]

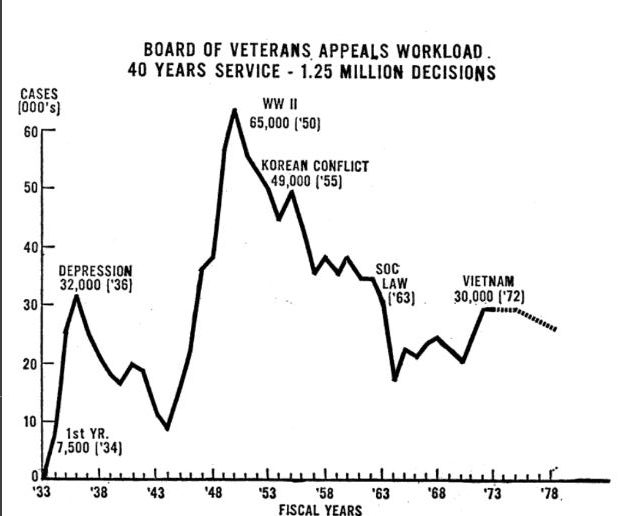

In November 1933, the president appointed Governor John G. Pollard of Virginia to be the first chairman of the Board. Roosevelt stated that “with Governor Pollard and the men who will be associated with him on this board, handling these border-line cases, I have every confidence that justice will be done to all.”[3] From that point on, Veterans could appeal directly to the national Board of Veterans Appeals, which was largely made up of career attorneys and physicians. According to VA’s 1934 annual report, the Board had rendered decisions in 7,523 cases in its first year. Its annual case load surged to 36,000 in 1936 before steadily falling to roughly 18,000 by the of the decade.

The huge increase in the Veteran population due to World War II and later conflicts had a direct impact on the Board’s workload. From 1944 to 1950, the number of appeals steadily grew as hundreds of thousands of World War II Veterans filed disability claims and applied for GI Bill benefits. In 1950 alone, the Board’s annual caseload reached a new high of 65,000 appeals. While the yearly number of cases decreased after 1950, the Board saw additional spikes in appeals during and after both the Korean and Vietnam Wars. By 1973, 40 years after its creation, the Board was averaging 30,000 cases per year and had heard a total of 1.25 million cases since 1933.

Since its inception, the Board has made it possible for Veterans to appeal VA decisions on their medical, education, and other benefit claims. Yet, until 1988, the Board had no external judicial oversight.[4] In other words, Veterans could not challenge the Board’s decisions in a non-VA court. There were two avenues for Veterans to appeal a Board decision, both of which were internal to VA. The first was a motion for reconsideration by the chairman, and the second was the reopening of a claim by a VA medical center or regional office. Otherwise, the Board’s decisions were final.

However, the Veterans Judicial Review Act, signed into law by President Ronald Reagan on November 18, 1988, created an independent court now known as the Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims (CAVC) that could review Board decisions. This law was passed less than a month after Reagan signed legislation to make the Veterans Administration a cabinet-level department. It also came on the heels of a spike in disputed benefits cases by Vietnam Veterans in the 1980s, who felt that their claims were being unjustly denied.[5] The Veterans Judicial Review Act also did away with a Civil War-era law prohibiting attorneys from charging more than $10 to represent Veterans in benefits cases and instead allowed attorneys to charge a ‘reasonable fee’ for representing Veterans before the Board and CAVC.[6] It also stipulated the Board’s chairman be appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. This act’s particular significance, however, was that, for the first time, Veterans could now appeal the Board’s decisions in a non-VA affiliated court. This helped ensure greater fairness in the evaluation and granting of Veterans’ benefits.

Throughout its history, the Board has handled Veterans’ cases in a different manner than other courts of law. First, it takes a non-adversarial approach to the cases. Instead of being pitted against the Veteran, VA works with the claimant to review the case and examine the evidence presented in order to arrive at a just decision on the appeal.[7] Additionally, the Board is bound by the Benefit of the Doubt Doctrine, meaning that if there is an equal amount of evidence proving and disproving a Veteran’s claim, the Board will side with the Veteran.[8] Furthermore, the Board’s standard of proof for a claim is “at least as likely as not.”[9] Under this doctrine, a Veteran needs only to provide evidence that a disability is at least as likely to be caused by military service as not for a claim to be accepted as valid. The Board’s decisions are also nonprecedential. Prior Board decisions are only binding for a specific case, rather than applicable to all future cases. [10]

Today, the Board typically issues over 95,000 decisions each year. During the 2024 fiscal year, it heard a record 116,192 appeals.

[1]Board of Veterans’ Appeals, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, https://department.va.gov/board-of-veterans-appeals/

[2] “Money Claims of Veterans Are Rejected,” Cincinnati Post, October 24, 1933.

[3] “Pollard Heads Board on Veteran Appeals,” Missoulian, November 25, 1933.

[4] “History,” United States Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims, https://www.uscourts.cavc.gov/history.php.

[5] Mary Stout, “VVA and the War to Win Judicial Review” (2018), https://vvaveteran.org/38-4/38-4_judicialreview.html.

[6] Barton F. Stichman, “THE VETERANS’ JUDICIAL REVIEW ACT OF 1988: CONGRESS INTRODUCES COURTS AND ATTORNEYS TO VETERANS’ BENEFITS PROCEEDINGS.” Administrative Law Review 41, no. 3 (1989): 365–97, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40709609.

[7] Zachary Stolz, “CCK LIVE: The ‘Non-Adversarial’ Nature of the VA Claims Process,” August 3, 2018, https://cck-law.com/blog/cck-live-the-non-adversarial-nature-of-the-va-claims-process/.

[8] April Donahower, “VA’s Benefit of the Doubt Doctrine,” August 31, 2018, https://cck-law.com/blog/vas-benefit-of-the-doubt-doctrine/.

[9]Jenna Zellmer, “VA’s Standard of Proof: “At Least as Likely as Not,” August 30, 2018, https://cck-law.com/blog/vas-standard-of-proof-at-least-as-likely-as-not/.

[10] 38 CFR § 20.1303 – Rule 1303. Nonprecedential nature of Board decisions. https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/38/20.1303

By Maddie Watts

Virtual Student Federal Service Intern, VA History Office

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

The Fall of Saigon 1975: A South Vietnamese Military Physician Remembers

"There was chaos in the streets when I made my way to the hospital on the morning of April 30, 1975. In a place of order, there was now great confusion. The director and vice director of the hospital were gone, making me, the chief of medicine, the highest-ranking medical officer."

Featured Stories

History of Former Whipple VA Directors Schmoll And McIntyre

Leadership change is something that happens constantly, whether it’s due to promotion, health, or other circumstances. At the Department of Veterans Affairs’ Northern Arizona Medical Center (formally known as Whipple VA Hospital) in Prescott, Arizona, directors have stayed in their position on average, three to five years. The shortest stint was 22 months, the longest was 16 years and two months. Most former directors moved on and retired elsewhere. However, two former directors, Paul N. Schmoll and Virgil I. McIntyre, either returned to or stayed in Prescott following their retirement. Both men are laid to rest at local cemeteries in the Prescott, Arizona, area.