Clara Barton earned lasting fame for her work ministering to the Union wounded during the Civil War and for founding the American Red Cross in the 1880s. But she also deserves to be remembered for a lesser-known chapter in her life sandwiched between these two episodes. In 1865, she opened at her own expense the Missing Soldiers Office on the third floor of a boarding house in Washington, D.C. Over the next four years, Barton and her small team of clerks answered thousands of inquiries from families desperate for information about their loved ones in the Union Army who had been captured or gone missing during the war. Her office succeeded in determining the fate or whereabouts of more than 20,000 soldiers. Her dogged efforts to track down the missing brought immeasurable relief or at least solace to anxious parents, wives, and siblings throughout the North who were still reckoning with the costs of the war.

Born in 1821 in North Oxford, Massachusetts, where she also spent her childhood, Barton earned her teaching certificate at the age of seventeen. She devoted the next fifteen years of her life to working as a schoolteacher before relocating to Washington, D.C. in 1854. There, she become one of the first women to work for the federal government, taking a job as a clerk at the U.S. Patent Office. She was living in the city when the Civil War broke out in 1861. In April of that year, a Union militia regiment from Massachusetts traveling through Baltimore was attacked by an angry mob of Southern sympathizers. The injured were transported to Washington for medical care. The ranks of the wounded included many men from her hometown. Barton volunteered to assist at the hospital and with this experience she found a new calling. During the Civil War, she worked tirelessly on behalf of the soldiers in the Union Army. She made frequent visits to encampments, field hospitals, and even battlefields to deliver food and medical supplies. Despite her lack of formal medical training, she also providing aid and comfort to the wounded. She tended to their injuries, read to them while they were recovering, and helped the men write letters home. She was given the nickname “Angel of the Battlefield” for her selfless labors to ease the pain and suffering of soldiers in need.

As the Civil War drew to a close in early 1865, Barton turned her attention to alleviating a different kind of suffering. Bags of mail were arriving at Army camps and hospitals, filled with letters from frantic relatives seeking information on soldiers reported as captured or missing. Seeing that the letters were going unanswered, Barton wrote to President Abraham Lincoln in February 1865, asking for permission to open a government office to respond to these requests. With Lincoln’s backing, she first traveled to Annapolis, Maryland, where former Union prisoners were arriving by the shipload from the South. Unable to make much headway due to the chaotic conditions and her own lack of resources, she departed Annapolis after just a few weeks.

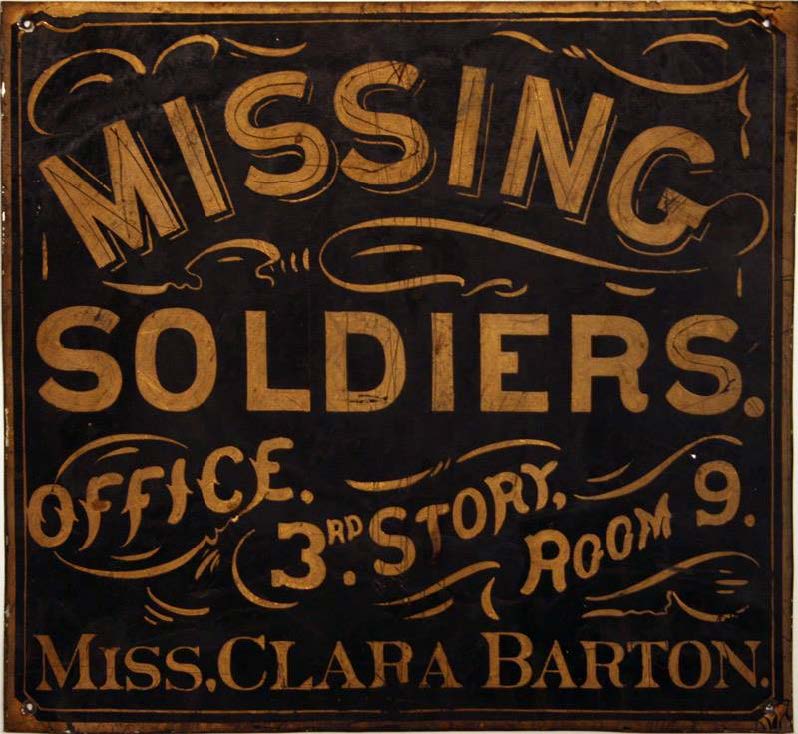

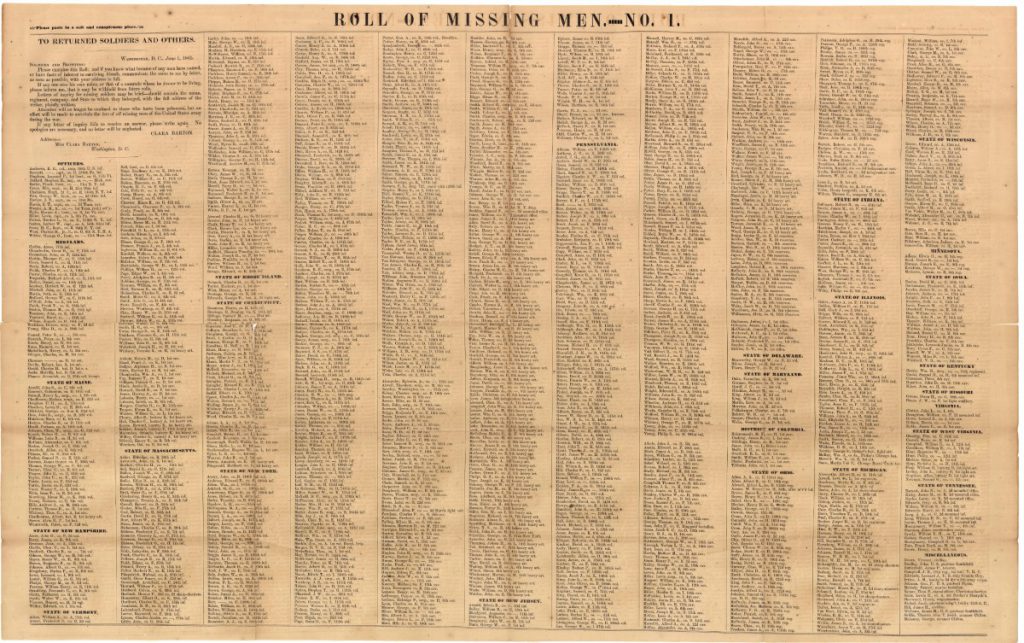

Once back in Washington, Barton opened the Bureau of Records of Missing Men of the Armies of the United States, using her own funds to rent a small space and hire several clerks. The sign outside the door read simply “Missing Soldiers Office.” She developed a system for gathering information and handling the inquiries that came pouring into the office at a rate of up to 150 letters a day. Barton collected all of the registers from prisons, hospitals, and records about burials she could find, although these were not always complete or accurate. She also turned to ex-prisoners of war, recognizing that they could be the best source of intelligence on the missing. From the letters she received, she compiled a “Roll of Missing Men” which she published roughly once a year. Andrew Johnson, who became president after Lincoln’s assassination, allowed Barton to use a government printing press to publish the lists. The first one, dated June 1, 1865, contained 1,533 names. Overall, her office released five rolls filled with more than 6,000 names. The broadsheets were distributed across the country, posted in government buildings and other public places, and often were reprinted in local newspapers, with instructions for anyone with information to contact her office.

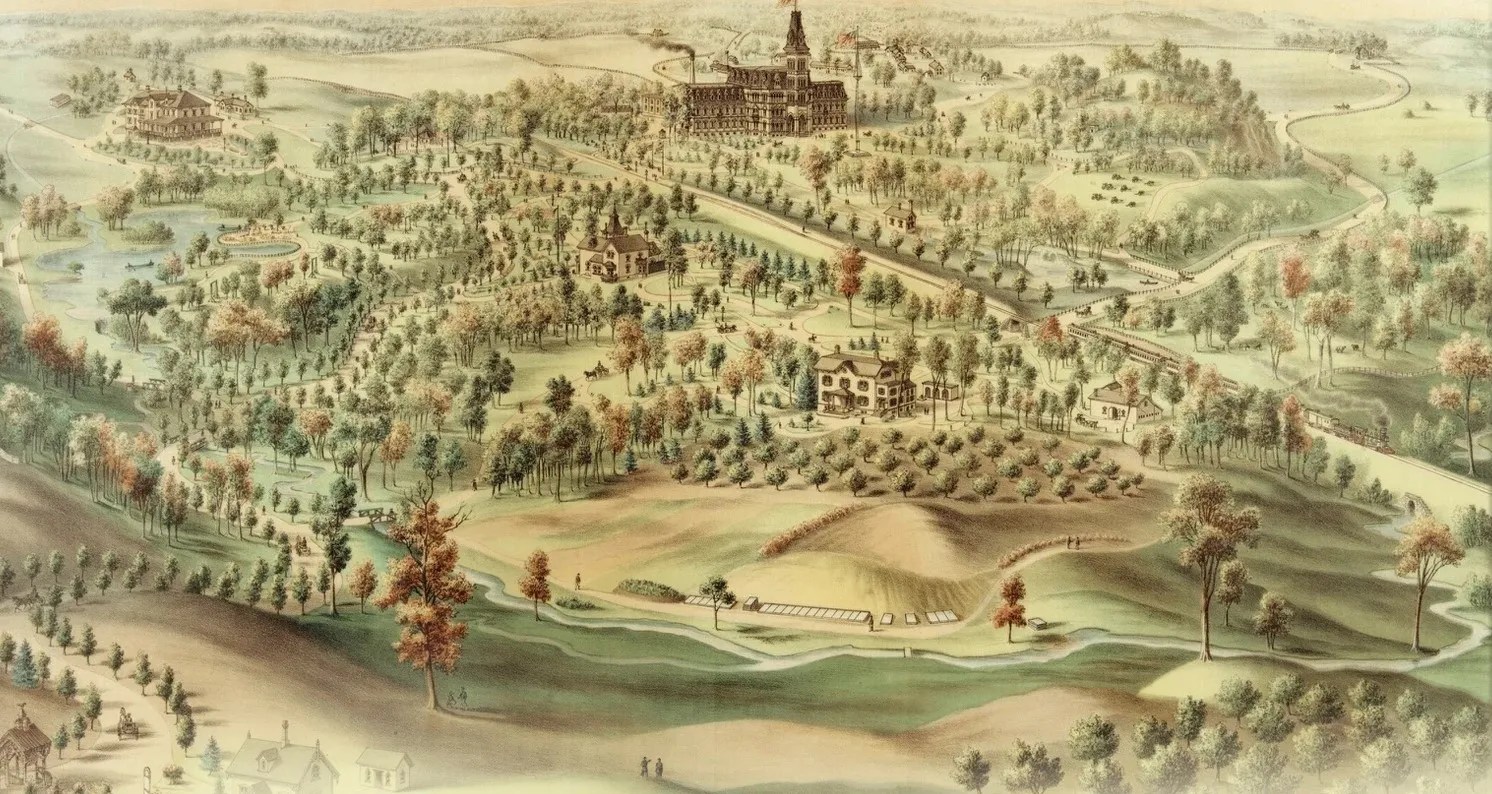

Barton had a breakthrough when she was approached by Dorence Atwater, a Union soldier who had been imprisoned at Andersonville, a notorious camp in Georgia that held thousands of Union soldiers. Atwater was responsible for burying the dead and he kept a list of their names and the location of their gravesites for the prison wardens. Fearful that Confederate officials would attempt to conceal the horrific death toll at the prison, Atwater made copies of the burial lists and smuggled them out when released. In June 1865, Barton accompanied Atwater on an Army expedition to Andersonville. While Atwater and a team of soldiers erected headstones and formally recorded the graves of over 13,000 men, Barton wrote to the families to notify them of the deaths.

After Barton returned from Andersonville, her office lapsed into inactivity as she ran out of money to pay her staff and purchase supplies. Letters and inquiries piled up throughout fall 1865, until Barton, with the help of her friend Francis Dana Barker Gage, a well-known suffragette and abolitionist, petitioned Congress for assistance. She appeared before the Joint Committee of Reconstruction on February 21, 1866, requesting reimbursement for her past expenses and funds to continue running the office. She was possibly the first woman to testify before Congress and was certainly the only woman to do so during the months of Reconstruction hearings. Congress authorized $15,000 in government bonds, which she used to hire staff and restart operations. Before they were finished, Barton and her clerks over a four year period received more than 63,000 inquiries, answered over 41,000, and helped locate more than 22,000 missing soldiers. Sometimes, Barton was able to reconnect soldiers with their families, but more often than not her office was the bearer of bad news. However, notification of death and burial location did bring closure and allowed wives and dependent children to apply for pension benefits. The office was occasionally contacted by the missing soldiers themselves, requesting that their names be taken off the rolls. Some of these men were deserters while others simply wanted to start a new life.

Barton continued running the Missing Soldiers Office into 1868. By this time, inquires had slowed to a trickle and Barton was exhausted, as she had maintained her job at the U.S. Patent Office throughout. At the recommendation of her physician, Barton traveled to Europe to recuperate. It was during this trip that she learned of the Red Cross movement to provide humanitarian aid to those injured in combat. She volunteered for the International Committee of the Red Cross and assisted in the delivery of relief to civilians during the Franco-Prussian War. Barton founded the American Red Cross in 1881 and served as president of the organization until 1904, when she resigned her position after twenty-three years of service. Never one to stay idle when she saw a way to be of service, Barton went on to form the National First Aid Society, which was later absorbed by the American Red Cross. She continued working and volunteering until the end of her life. She died on April 12, 1912, at the age of ninety.

By Alexandra Boelhouwer

Virtual Student Federal Service Intern, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

A Brief History of the Board of Veterans’ Appeals

On July 28, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6230 creating the Board of Veterans’ Appeals (BVA). The BVA was created as part of the Veterans Administration (VA), which had been established only three years earlier.

Featured Stories

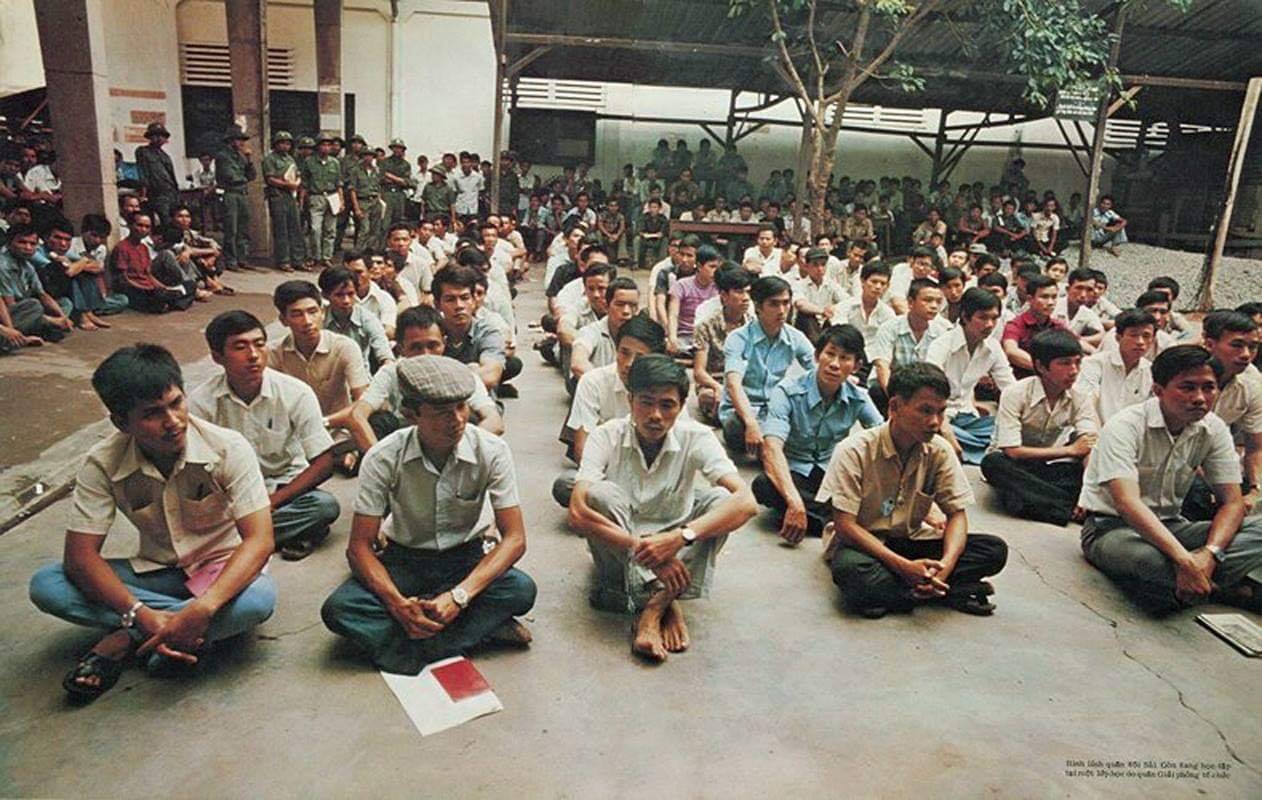

The Fall of Saigon 1975: A South Vietnamese Military Physician Remembers

"There was chaos in the streets when I made my way to the hospital on the morning of April 30, 1975. In a place of order, there was now great confusion. The director and vice director of the hospital were gone, making me, the chief of medicine, the highest-ranking medical officer."