“The world cannot afford to lose the talents of half its people if we are able to solve the many problems that beset us.” – Dr. Rosalyn Yalow

In her Nobel Prize banquet speech, Dr. Rosalyn Yalow stated, “We must believe in ourselves or no one else will believe in us; we must match our aspirations with the competence, courage, and determination to succeed; and we must feel a personal responsibility to ease the path for those who come afterwards.”

Determination was intrinsic to young Rosalyn, growing up in the 1920s in the South Bronx to a Jewish working-class family. Her parents, Simon and Clara Sussman, immigrated to the United States from Eastern Europe and started a small business in cardboard and packing twine sales. In America, the Sussmans saw opportunity, and when they looked at their two children, Rosalyn and Alexander, they saw a world of hope. From a young age, Simon instilled in his daughter the notion that women could succeed in anything they set their minds to, encouraging her to follow her passions regardless of society’s gender norms.

An enthusiastic student, Rosalyn excelled in her studies, graduating in 1941 at 19 as the Hunter Colleges first physics major. Her tenacious approach to science yielded her an impressive resume fit for any university’s candidacy program. Despite her achievements, universities continually rejected her applications for a graduate fellowship since “as a Jew and a woman, they believed that she would never get a job in the field.”

Yalow’s search for a fellowship occurred while the country was mobilizing for World War II. As a result, graduate positions given to enlisted men soon became vacant, earning her a position as both a student and teaching assistant at the University of Illinois at Urbana. While her husband, Aaron, a fellow physics graduate was able to find employment after graduation, Rosalyn had a more difficult time, accepting a teaching position at Hunter College. Since she was unable to perform research as a professor at the college, she volunteered at one of Columbia University’s medical labs where she had experience with radiotherapy, a newly emerging field.

As a result of her interest in radiotherapy, Yalow joined the Bronx Veterans Administration Hospital (currently the James J. Peters Veterans Affairs Medical Center) in 1947. She began her work in a converted janitor’s closet, transforming it into her own small laboratory space and teaming with Solomon A. Berson, an accomplished medical doctor. In 1950, she overcame the odds for women in her field and was promoted to assistant chief of the radioisotope project at the VA hospital

In one of their early research projects, Berson and Yalow worked on uncovering the mechanics of insulin injections in the human body. Through the use of radioactive iodine, they were able to trace the beef-derived insulin throughout the body, ultimately concluding that these injections “immunized patients so that they developed insulin-binding antibodies.” In their discovery, they developed a groundbreaking scientific technique they called radioimmunoassay or RIA. This was a historic breakthrough in science since it was the first technique that harnessed the power of radioisotopes to follow how antigens reacted with antibodies.

Today, the technique of RIA is used across the sciences including in screening for hepatitis in blood banks, correcting hormone levels in affected individuals, and in creating the most effective dosages of drugs and antibiotics.

Accolades and opportunities poured in for Yalow. She was elected to the National Academy of Sciences and became a research professor in the Department of Medicine at Mount Sinai. The pinnacle prize for her efforts came when she was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1977 for her work with radioimmunoassay. Yalow was the second woman to receive the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine, and remains VA’s only female Nobel Prize awardee.

After her expansive and historic work with radioimmunoassay, Yalow continued to work at the Bronx VA hospital until her retirement in 1991. Yalow passed away on May 30, 2011.

By Parker Beverly

VA History Office intern and Wake Forest undergraduate student

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

A Brief History of the Board of Veterans’ Appeals

On July 28, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6230 creating the Board of Veterans’ Appeals (BVA). The BVA was created as part of the Veterans Administration (VA), which had been established only three years earlier.

Featured Stories

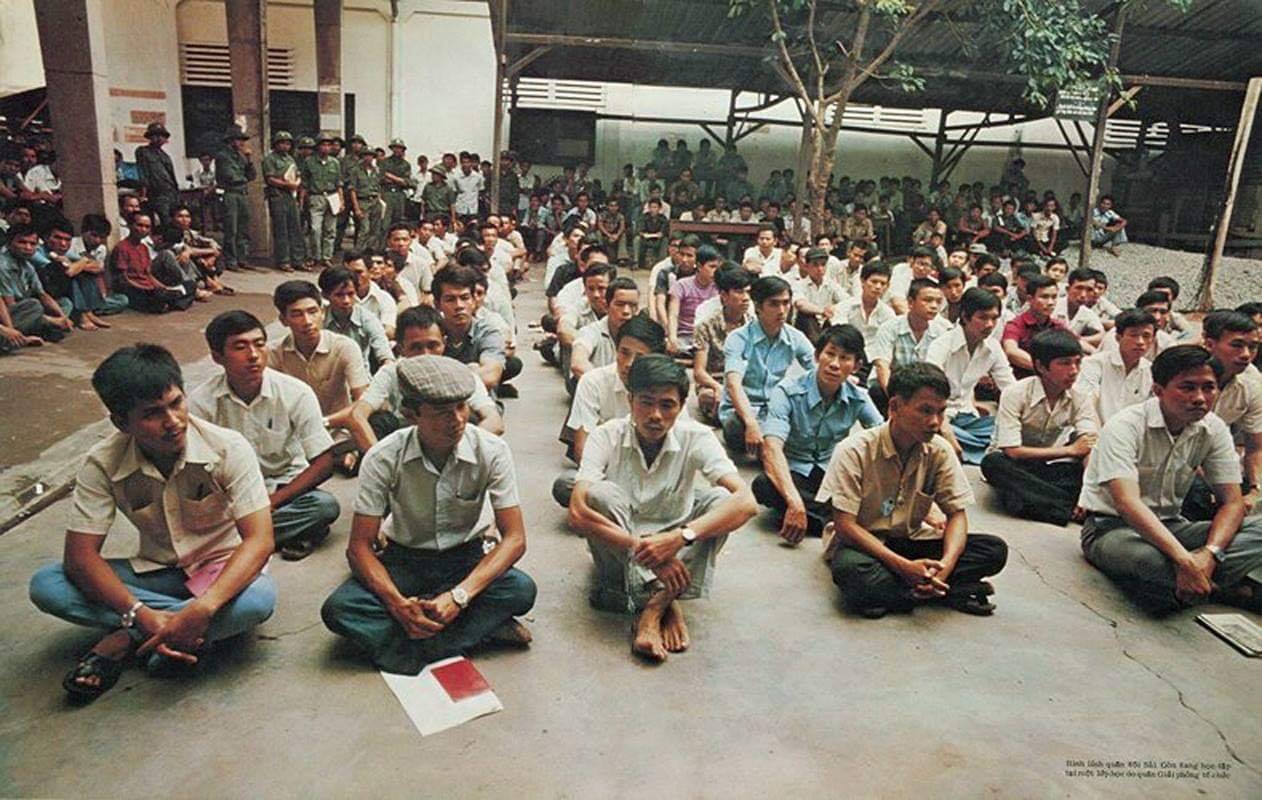

The Fall of Saigon 1975: A South Vietnamese Military Physician Remembers

"There was chaos in the streets when I made my way to the hospital on the morning of April 30, 1975. In a place of order, there was now great confusion. The director and vice director of the hospital were gone, making me, the chief of medicine, the highest-ranking medical officer."