On the night of November 2, 1917, Company F of the 16th Infantry Regiment, First Infantry Division, held off a night raid from German forces at Bathlémont, France, and sustained the first of many combat casualties and prisoners of war (POWs) of the American Expeditionary Forces in World War I (1917-1918). Among them were Sergeant Edgar M. Halyburton and Private Clyde Grimsley, who were captured by the Germans and became some of the first American prisoners of the war in the conflict.1

Sgt. Halyburton of Stoney Point, NC, enlisted in the U.S Army in 1909 and served in Mexico during the Punitive Expedition against Pancho Villa (1916-1917). He was deployed to France shortly after the United States entered into the war. When captured on the night of November 2, Halyburton and other captured Americans were eventually taken to Tuchel Prison Camp in West Prussia where they encountered harrowing conditions. Faced with lack of food and clothing, they were forced into heavy labor; tasked with harvesting lumber and carting wood miles to camp through the winter. Halyburton quickly sought to improve camp conditions for himself and fellow prisoners. He began sending postcards to the Red Cross asking for parcels (which included food) to be sent to the camp so that those imprisoned could be sustained throughout the winter.2 Four months later, Red Cross parcels were finally received.

After seven months, Halyburton was transferred from Tuchel to Rastatt Prison Camp (Baden, Germany) where he remained until the armistice. At Rastatt, he made it his mission to establish a sense of order in the camp and eliminate German propaganda from influencing the morale and loyalty of American prisoners. His 500 fellow American prisoners elected him as their camp commander to attain this mission.3 Halyburton established a firm camp structure that assured each man a job and handpicked an intelligence staff to monitor the effectiveness of German propaganda on POWs.4 Recognized as head of American prisoners by the Germans running the camp, Halyburton was officially recognized as the leader of all present and incoming Americans in the camp.5 For his leadership during while imprisoned, Halyburton was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal – one of the first enlisted men to receive the honor.6

Pvt. Clyde Irving Grimsley, an accomplished cornetist, enlisted in 1917 as a commissioned band leader. Eager to fight, he requested a transfer to the infantry with the hopes of joining the action in France.7 Originally from Stockton, KS, Grimsley was captured with Halyburton and was taken to Tuchel Prison Camp after spending 30 days confined at Metz (in German occupied France).8 After being at Tuchel for three months, Grimsley contracted tonsillitis and bronchitis and was admitted to the camp hospital.9 After a five week recovery he took on the role of orderly, assisting two American doctors in the camp.10

Grimsley also utilized his musical talents during captivity. He played concerts in the camps and provided music at the funeral of an American prisoner.11 Grimsley was transferred among various prison camps until he was freed in December, 1918 and returned home three months later on February 19, 1919.12

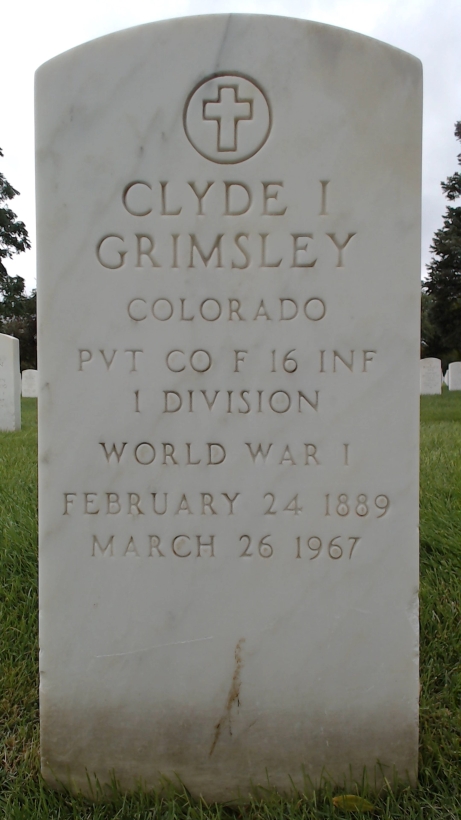

Following the war, Pvt. Clyde Irving Grimsley returned and married his fiancée, Mary Crandall. Grimsley died in 1967 and is interred in Fort Logan National Cemetery (Section P, Site 1389).

Footnotes

- John Pershing. Cable Number 286, Headquarters American Expeditionary Force, 14th November 1917. November 14, 1917. WWI Military Cablegrams – AEF and War Dept. RG 120.209257134. National Archives & Records Administration. ↩︎

- “Yankee Fights Propaganda in Prison Camp.” The Herald and News. April 18, 1919. Chronicling America. ↩︎

- Commandant of Prisoners.” The Daily Gate City. April 16, 1919, Wednesday edition. Chronicling America. ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- “Yankee Fights Propaganda in Prison Camp.” The Herald and News. April 18, 1919. Chronicling America. ↩︎

- Office of The Adjutant General. Decorations United States Army 1862-1926. Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1927. P. 723. ↩︎

- “From Hun Prison Camp.” Abilene Weekly Reflector. July 18, 1918. Chronicling America. ↩︎

- “His Camp Worst: Clyde Grimsley Relates Horrors of Hun Prisoners.” The Salina Evening Journal. March 6, 1919. Newspapers.com. ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Spanish Embassy in Berlin. “Prisoner Hospital Tuchel American Report No.33.” State Department, June 7, 1919. Fold3.com ↩︎

- “Transport Arrives Loaded With Troops.” Albuquerque Morning Journal. February 19. Chronicling America. ↩︎

By Nalia Warmack

Intern, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

A Brief History of the Board of Veterans’ Appeals

On July 28, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6230 creating the Board of Veterans’ Appeals (BVA). The BVA was created as part of the Veterans Administration (VA), which had been established only three years earlier.

Featured Stories

The Fall of Saigon 1975: A South Vietnamese Military Physician Remembers

"There was chaos in the streets when I made my way to the hospital on the morning of April 30, 1975. In a place of order, there was now great confusion. The director and vice director of the hospital were gone, making me, the chief of medicine, the highest-ranking medical officer."