In 1882, the Pension Bureau hired 770 new clerks, doubling the size of its work force. The additional manpower was necessary to keep up with the explosive growth of the pension system after the Civil War. That same year, Congress appropriated $250,000 for the construction of a Pension Bureau building headquarters to accommodate the expanding staff and the millions of records contained in its files. Congress entrusted the task of designing the building to General Montgomery C. Meigs, who was retiring from the U.S. Army after forty-five years of service. He had spent the last twenty-one years as the Quartermaster General of the Army, but his military career began as a West Point-trained engineer. Before the Civil War, Meigs was acclaimed for his work supervising the construction of two of Washington’s architectural marvels: the 12-mile-long Washington aqueduct and the U.S. Capitol’s iron dome.

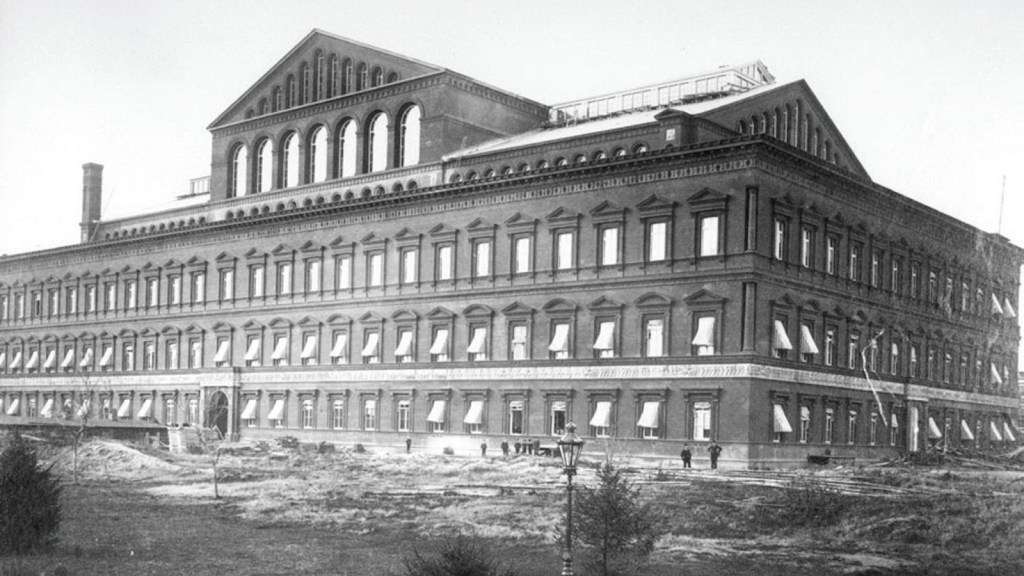

Meigs designed the Pension Bureau building headquarters on a grand scale and in a style that was atypical for the capital. While neoclassical was the preferred style of the day for federal buildings In Washington, Meigs drew inspiration from Italian Renaissance architecture and modeled his creation after a sixteenth century Roman palazzo. An estimated fifteen million red bricks went into its construction and the finished product filled a city block in downtown Washington. Meigs used brick as his primary building material because it was both economical and fireproof, a critical quality considering the irreplaceable pension records stored within. Despite his efforts to control costs, the final price tag for the building came to just under $900,000.

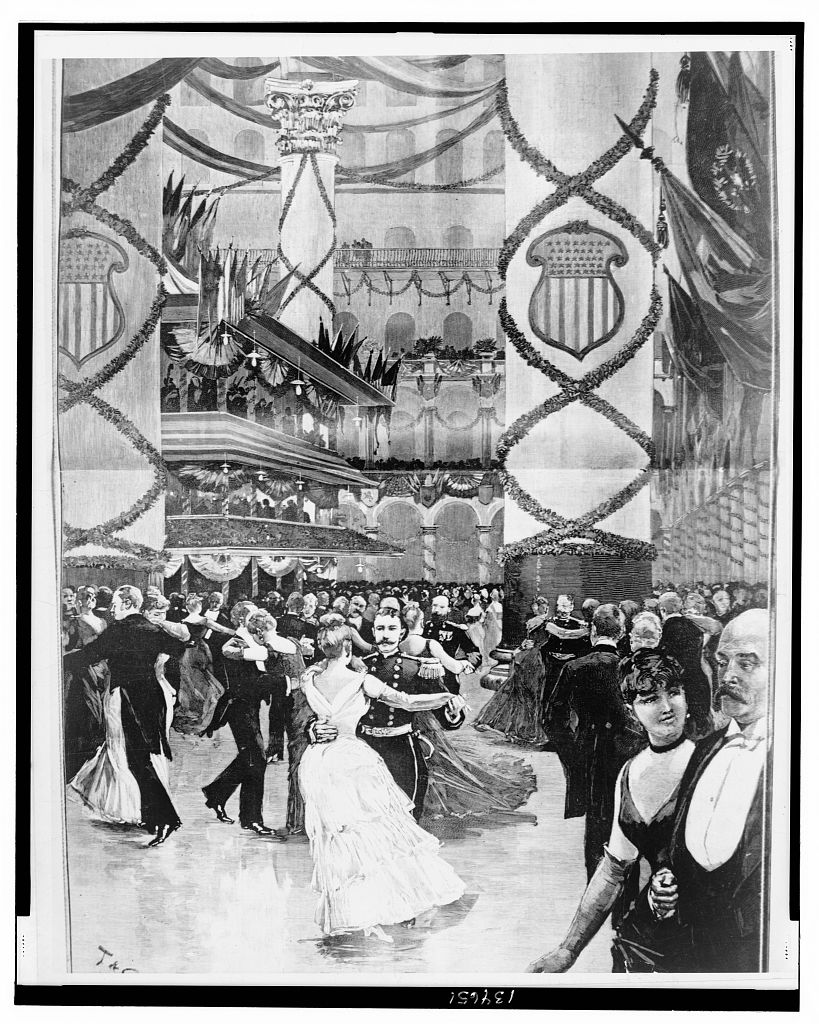

The Great Hall measuring 316 feet long by 116 feet wide dominates the Pension Bureau building’s interior. Within the hall, eight massive brick Corinthian columns—believed to be the tallest interior columns in the world at the time—support a glass and metal roof that reaches a height of almost 160 feet. A two-story arcade along the perimeter of the Great Hall provides access to office space. The entire structure is open, airy, and filled with natural light.

Meigs added several innovative elements to enhance the utility of the building. It was cooled by an ingenious system that drew fresh air through vents in the outer walls and expelled hot air through ceiling skylights. Elevated rails built into the floors allowed baskets of papers to move easily between offices and a dumbwaiter system transferred documents between floors. The four stairways featured extra-wide treads and shallow risers to accommodate hobbled Veterans. As a final creative flourish, Meigs commissioned artist Caspar Buberl to sculpt a terra cotta frieze for the exterior. Encircling the entire building above the first floor, the 1,200-foot frieze depicts Union soldiers and sailors in different groupings and poses.

Pension workers moved into the headquarters in 1885, although construction was not complete until 1887. Besides serving as a home for the Pension Bureau and its voluminous records, the building was also used for ceremonial occasions, including presidential inaugural balls. Meigs boasted the Great Hall had a seating capacity of 11,000, a claim put to the test by the ball for President Benjamin Harrison in 1889 that drew 12,000 guests. The Pension Bureau departed the location in 1926 and another federal agency, the General Accounting Office, took its place. Other government tenants followed in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1980, an act of Congress designated it as the National Building Museum under the direction of a private, non-profit educational organization. Five years later, the building was designated a National Historic Landmark. Today, the National Building Museum hosts exhibitions devoted to exploring and understanding the built environment.

By Jeffrey Seiken, Ph.D.

Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 100: Burn Pits 360 Logo

A year after returning from Iraq with severe respiratory problems in 2008, Capt. Le Roy Torres and his wife founded Burn Pits 360 to raise awareness of the health hazards of burn pit emissions. Over a decade of persistent advocacy by Burn Pits 360s and other Veterans groups paid off with passage of the PACT Act in 2022, the largest expansion of Veterans benefits since the 1944 GI Bill.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 99: Bank Check from Manila Loyalty Room

After World War II, U.S. Army investigators in the Philippines turned over a huge collection of captured documents, intelligence reports, press clippings, and Japanese banks checks to the VA office in Manila. The Manila office stored the collection in the “Loyalty Room,” so named because VA used the checks and other records to evaluate the wartime allegiance of Filipino Veterans applying for benefits.