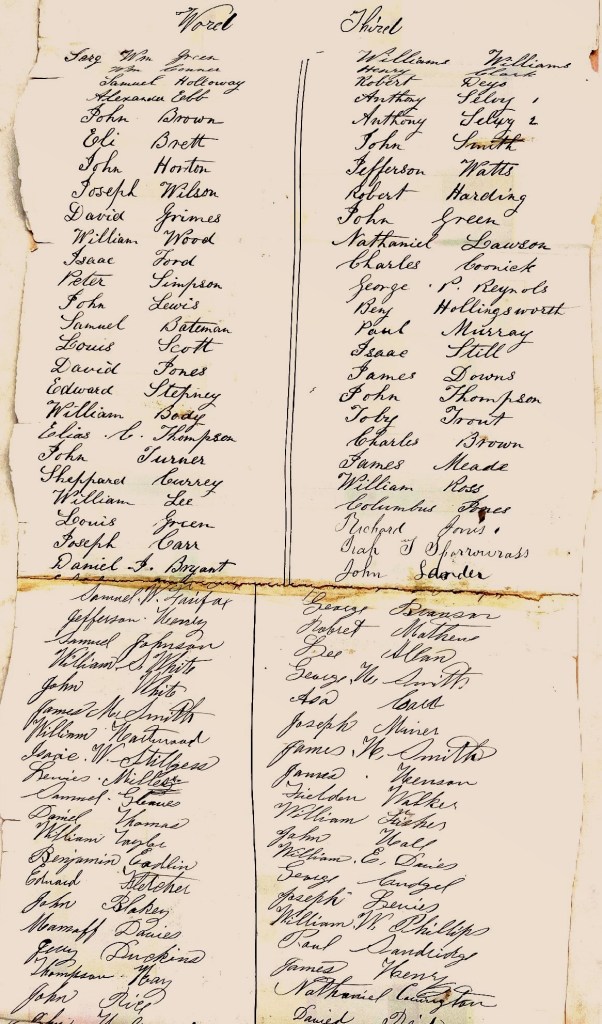

Just after Christmas in 1864, African American soldiers recuperating at the United States Colored Troops (USCT) L ‘Overture General Hospital in Alexandria, Virginia, submitted a petition for the right to burial alongside their White counterparts in the city’s Soldiers’ Cemetery, one of the first national cemeteries established by the U.S. government during the Civil War. To accompany the petition, the aggrieved soldiers included their names—443 in total—arranged by hospital ward and pasted together into a single roll that stretched nearly ten feet in length when unfolded.

Alexandria’s proximity to the nation’s capital, along with its railroads and Potomac River access, made it a key strategic military center and a place of sanctuary for those who had escaped slavery. The Union Army quickly occupied the city after Virginia seceded and it became the hub from which food, ammunition, forage, and soldiers traveled to Virginia battlefields. It also became a hospital center for sick and wounded soldiers from those battlefields. Numerous “contrabands”—the U.S. government’s designation for formerly enslaved African Americans who took refuge behind Union lines—congregated in the city as well. Black Union soldiers became a presence after President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, permitting the War Department to enlist African Americans without restriction in USCT regiments.

Much of the military activity in Alexandria centered around the Army’s Quartermaster Department, which was responsible for moving and supplying troops. Brevet Colonel James C. Lee supervised Alexandria’s quartermaster activities from 1863 to 1866. One of his duties was overseeing the burial of military dead in the area. Albert Gladwin, a White Baptist minister from the North who served as Superintendent of Contrabands in the city, worked concurrently with the military. Gladwin established the Contraband and Freedmen’s Cemetery to bury African Americans who died, largely from disease contracted in overcrowded and unsanitary living conditions.

Control between the military and Contraband Administration blurred with the arrival of the USCT. Quartermaster Lee set aside a plot in the Soldiers’ Cemetery for Black soldiers and some were buried there. Gladwin, however, felt that these dead were his responsibility and he proceeded to bury about 120 in his cemetery. The issue of where these men should be interred came to a head when hospitalized soldiers in the USCT made known that they would only escort their dead for burial in the military cemetery. The following day, Gladwin posted guards at the gates of the military cemetery, stopped a Black burial escort, arrested its hearse driver, and diverted the body to the Contraband and Freedmen’s Cemetery. That night, African American soldiers created their petition, which was forwarded to Colonel Lee. They presented their case in stirring language that still possesses the power to move:

We are not contrabands, but soldiers of the U.S. Army, we have cheerfully left the comforts of home, and entered into the field of conflict, fighting side by side with the white soldiers, to crush out this God insulting, Hell deserving rebellion. As American citizens, we have a right to fight for the protection of her flag, that right is granted, and we are now sharing equally the dangers and hardships in this mighty contest, and should share the same privileges and rights of burial in every way with our fellow soldiers who only differ from us in color.

The authority for resolving the dispute rested with Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs. Lee wrote to Meigs that “the feeling on the part of the colored soldiers is unanimous to be placed in the military cemetery and it seems but just and right that they should be.” Meigs wholeheartedly agreed. He ordered all Black soldiers to be buried in the military cemetery and had those already in the segregated cemetery reinterred so they could be laid to rest alongside their comrades in arms of either color. Gladwin was removed from his position two weeks later.

By Richard Hulver, Ph.D.

Historian, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.