When World War I erupted in Europe in August 1914, the United States stayed neutral but the nation quickly became a major supplier of industrial and agricultural goods to France and England. To protect this valuable trade, Congress established the Bureau of War Risk Insurance (BWRI) within the Treasury Department to insure American ships and cargo “against loss or damage by the risks of war.”

After the United States officially entered the war in April 1917, BWRI’s functions expanded dramatically. At the insistence of Treasury Secretary William G. McAdoo, Congress made BWRI responsible for administering the array of benefits the government offered to the soldiers and sailors serving in the war. The benefits included a supplemental allowance to dependents of enlisted personnel who allotted part of their own pay to this purpose, compensation for death and disability, and government-subsidized insurance. McAdoo wanted oversight of these programs out of the belief that his department would be a better steward of the governments’ money than the Department of Interior’s Pension Bureau, which managed benefits for Veterans of earlier conflicts.

Almost overnight, the BWRI found itself transformed from a small, largely anonymous office with a staff of about twenty into one of the most important and high-profile agencies in the federal government. Its scope of activities was enormous. From the time it took up its new duties in October 1917 through June 1918, BWRI mailed out over 3.2 million checks totaling about $97 million to the families of servicemen participating in the allotment and allowance program. By October of that year, BWRI had also logged applications from more than 4 million soldiers and sailors for insurance that indemnified them against death or total disability to the amount of almost $36 billion or $8,700 per policy.

To handle its vastly increased workload, the BWRI embarked on a mad scramble from late 1917 through 1918 to hire thousands of additional employees. By February 1918, the agency had 2,300 people on its payroll, but that was nowhere near enough to process the applications, claims and other paperwork that flooded its offices. By July, close to 7,000 men and women were on the job and the numbers continued to grow.

The bureau tried to increase efficiency and improve output any way it could. It organized clerks into day and night shifts, set up its own training program for new typists, and brought aboard teachers from local schools and college professors on summer break as temporary labor. The agency also employed a variety of labor-saving mechanical devices such as addressographs to eliminate typing of envelopes, automatic typewriters, and check-printing machines that could churn out 60,000 checks a day.

The BWRI’s ever expanding workforce quickly exceeded its allocated offices in the Treasury Building in Washington, forcing the agency to park the overflow wherever it could find vacant space. The bureau’s 1918 annual report to Congress ruefully stated that its employees “have been housed in 15 separate structures, most of them poorly adapted to the work.” In one of these structures, the city’s Center Market on Pennsylvania Avenue, the agency installed some 600 clerks in the unheated dance hall on the building’s top floor. During the winter, these hapless workers experienced “adverse conditions, which sometimes approached actual hardship,” a Washington newspaper reported. Equally unfortunate were the BWRI employees who set up shop in a garage in the business district.

The agency’s staff found far more comfortable accommodations at the Smithsonian’s new National Museum (now the National Museum of Natural History). Construction on the building had been completed just before the war in 1911. At the direct request of President Woodrow Wilson in the fall of 1917, the museum made available to the bureau 25,000 square feet on the first floor. However, the Secretary of the Smithsonian, Charles D. Wolcott, rebuffed the president’s appeal for yet more space on the second and third floors out of concern for the safety of its collections.

At first, the museum remained open to visitors even as BWRI clerks labored away at makeshift desks in the foyer and adjoining rooms. In July 1918, the president came calling again and this time Smithsonian officials agreed to turn over the entire building to the government.

The takeover of the National Museum was only temporary, however, as Treasury Secretary McAdoo had already secured a new home for the bureau. Earlier in the year, McAdoo had negotiated the purchase of the 11-story building going up on the site of the old Arlington Hotel on Vermont Avenue by the White House. The $4.2 million price tag raised some eyebrows in the press, but the acquisition solved the BWRI’s office space problems once and for all. The bureau began moving personnel into the building in February 1919. Most of the work of transporting the agency’s voluminous files and records occurred at night so as to minimize the disruptions to its operations.

The Bureau of War Risk Insurance survived the war by only two and a half years, replaced in 1921 by the Veterans Bureau. However, from the time BWRI took occupancy in 1919 to the present, the building on Vermont Avenue building has remained the headquarters of the federal agency – from the Veterans Bureau to the Veterans Administration to the modern-day Department of Veterans Affairs – charged with delivering government benefits and services to Veterans.

By Alexandra Boelhouwer, Virtual Student Federal Service Intern, Veterans Benefits Administration, and Jeffrey Seiken, Ph.D., Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

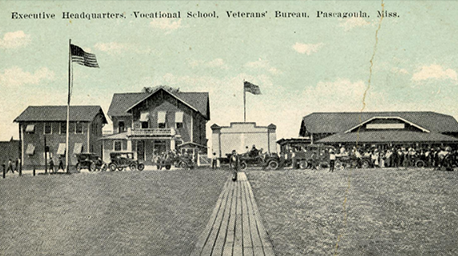

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.