In 1816, the vestry of Christ Church reserved 100 plots in the 4.5-acre Washington Parish Burial Ground for the interment of congressmen who died in office. Congressional Cemetery, as it is known today, now occupies 35 acres of land in the southeast section of Washington, DC, and has served as the final resting place for scores of elected officials and notable Washingtonians. The more than 60,000 gravesites include 806 maintained by VA. Some 168 of the VA sites are adorned with one of the most distinctive markers to be found in the cemetery—the iconic cenotaphs designed by Benjamin H. Latrobe, the nation’s first professional architect.

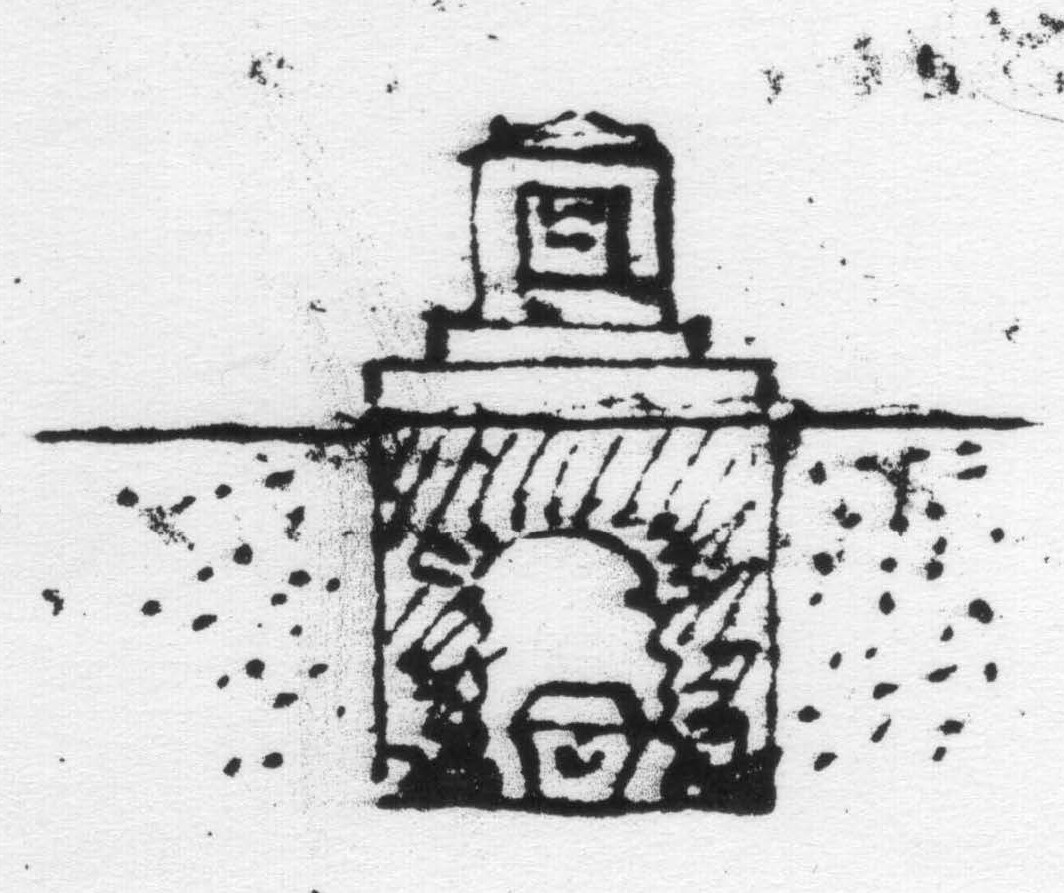

Derived from the Greek phrase meaning “empty tomb,” the word cenotaph traditionally refers to a monument erected to honor someone buried elsewhere. Latrobe came up with the design for the Congressional cenotaphs while working on the repair of the U.S. Capitol, which had been damaged by the British during the War of 1812. The sketch from his journal dating from 1816-17 shows the monument along with a casket placed in a chamber underneath. Fifty of the cenotaphs later installed in the cemetery conform to this vision and memorialize individuals who were actually interred there. The other 118 are truer to the meaning of the term and commemorate persons buried at another location.

Their simple, geometric design reflected Latrobe’s disdain for intricate early nineteenth-century grave markers.

“The object of erecting monuments to the dead is assuredly to perpetuate the memory of their merits,” he wrote, but “the monuments usually put up in our Church Yards are the most ingeniously contrived to last as short a time as possible.” His design required just a few pieces of sandstone, with the square foundation supporting a smaller block topped by a conical cap.

The entire structure measured 5.5 feet at its base and was just a shade taller in height. An inscribed marble panel set in one side identified the name of the deceased. Arranged in long, straight rows in the cemetery, the cenotaphs provided a sharp contrast to the disorderly burial sections neighboring them.

The oldest interment marked with a cenotaph was, fittingly enough, that of the first congressman to be buried in the cemetery, Connecticut Senator Uriah Tracy (1755–1807). James Lent (1782–1833), a representative from New York, became the first person memorialized with what might be called a genuine cenotaph. Six years after he was laid to rest in his family’s burial ground in New York, Congress installed a cenotaph to honor his memory.

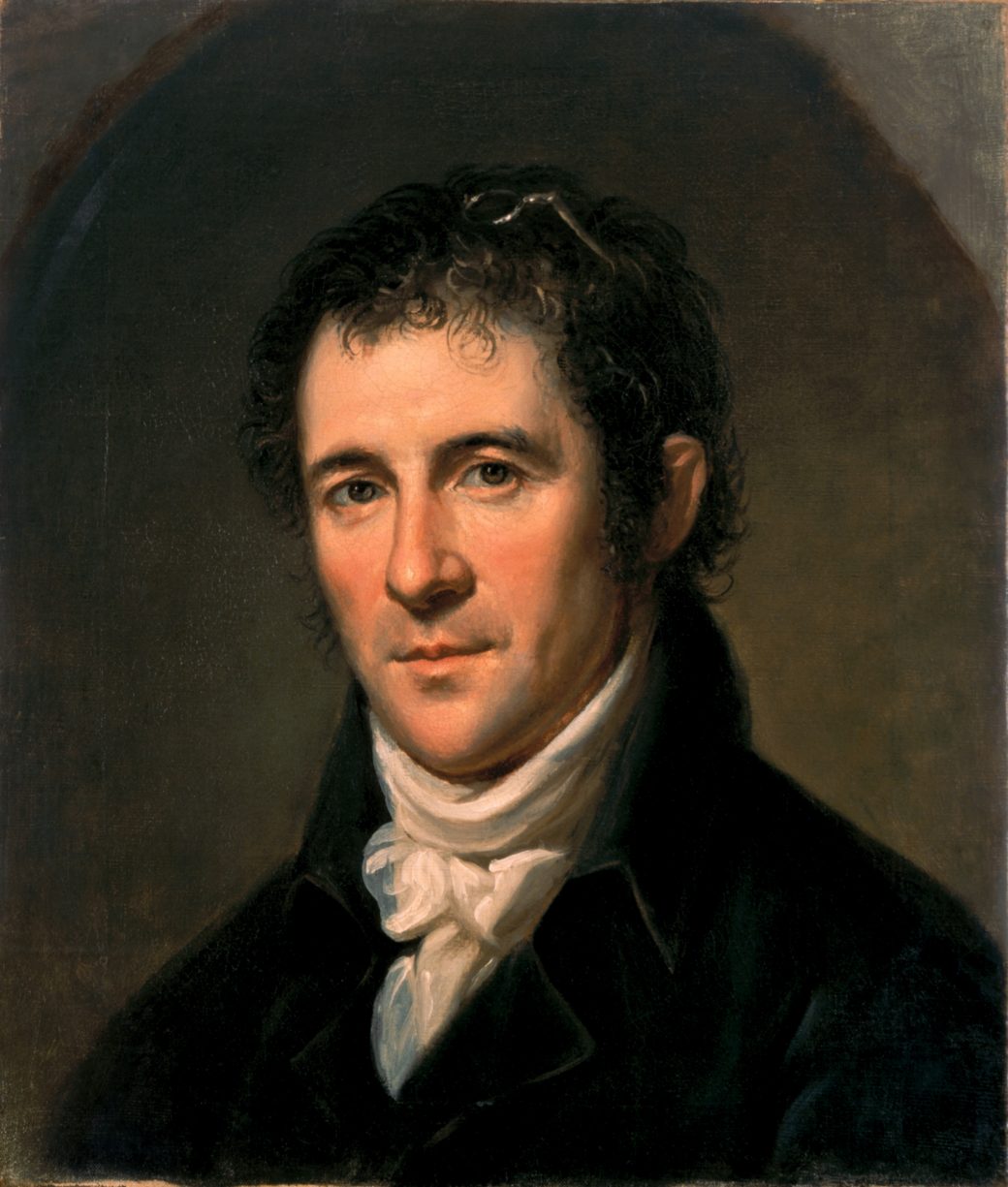

In addition to the cenotaphs, Latrobe left his imprint on many building projects in the nation’s capital during its formative years. Born in Britain in 1764, he studied engineering and architecture before immigrating to the United States at the age of 32. As the second Architect of the Capitol, he produced its striking Neoclassical interiors, and he also had a hand in the design of the Navy Yard, the President’s House, and St. John’s Church.

Many of the city’s buildings were constructed using the same fragile, brown-to-light-gray sandstone as the cenotaphs. Quarried from the Aquia Creek in nearby Stafford County, Virginia, the sandstone was easy to carve, but this quality also contributed to its weather-related deterioration. To protect the sandstone, it was sometimes painted or covered in a limestone wash.

Use of the Latrobe cenotaphs ceased in 1876. Their fall from favor is often attributed to Congressman George F. Hoar of Massachusetts, who said “being buried beneath one would add new terrors to death. . . . I cannot conceive of an uglier shape.” The markers were more or less ignored until 1928, when the U.S. Army quartermaster reported that 116 were in fair condition and the remainder dilapidated. Rather than undertaking a costly repair of the cenotaphs, which he considered the “most unattractive,” he proposed replacing those that marked an actual burial site with “suitable granite or marble monuments.” The Army had other ideas. In the 1930s, it replaced the cenotaphs that could not be restored with identical markers.

Throughout the nineteenth century, the U.S. government paid for improvements to Congressional Cemetery. However, despite its reputation as a “national burying ground,” there is no connection between Congressional and the system of national cemeteries established by Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War for the burial of Union dead and generations of Veterans ever since. In 1953, the cenotaphs were among the 806 gravesites that became federal property through a land swap between the cemetery and the U.S. Army. In 1973, VA assumed responsibility for these sites along with most of the country’s national cemeteries.

Today the cenotaphs are counted among VA’s oldest and most significant “private” grave markers. In 2007-2008, VA completed a comprehensive project to repair and restore the monuments through a partnership with the National Park Service. Material was salvaged from cenotaph components. Preservationists also employed Aquia Creek sandstone left over from a 1950s renovation of the Capitol as well as other types of stone compatible in color and texture.

The project was awarded the 2009 District of Columbia Award for Excellence in Historic Preservation, while Congressional Cemetery in its entirety was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2011. Latrobe’s cenotaphs have withstood the ravages of time and the barbed comments of critics to remain an indelible part of the cemetery’s landscape.

By Sara Amy Leach

Senior Historian, National Cemetery Administration (Retired)

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.