After the Vietnam War, the nation was eager to put the divisive and unpopular conflict behind it. However, the 3.4 million Veterans who served in the Vietnam theater did not have that luxury. Over 150,000 were seriously wounded in combat and many times that number were exposed to toxic herbicides or suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder when they returned home.

Army captain Max Cleland was one of the many Veterans who struggled with the aftereffects of the war. In 1968, he lost both legs and part of an arm in a grenade accident while deployed to Vietnam. Following his arduous rehabilitation at a military hospital and his discharge, he had trouble obtaining properly fitting prostheses or meaningful mental health counseling from VA. As a result of that experience, he made it one of his missions in life to secure better treatment for his fellow Vietnam Veterans.

“It is up to the agencies of this government,” he testified before Congress in 1969, “to make an added effort in [Vietnam Veterans’] behalf to meet their special physical and psychological problems.” His advocacy for Veterans led him to a career in politics. In 1977, President Jimmy Carter picked him to lead the Veterans Administration. His appointment at age 34 made him the youngest person to run the agency and the first Vietnam Veteran to occupy the top post.

During his tenure at VA, Cleland delivered on his goal of providing readily accessible mental health and readjustment counseling designed expressly for Vietnam Veterans. In 1979, VA launched an initiative called Operation Outreach to establish community-based Vet Centers. In a 1980 interview, Cleland explained the organizing principle of the centers: “These centers will provide service on a walk-in basis, without the need for prior hospitalization or the stigma of a mental health unit record.”

In the rush to get the program up and running, some of the first centers opened in garages, basements, and other temporary spaces. However, within a year, VA had established 91 centers in storefront locations in cities across the country. The centers were typically staffed by a team of four, including two counselors who were often Veterans of the war themselves. They offered a range of social, psychological, and referral services for Veterans and their family members. Above all, the Vet Centers served as a safe space for Vietnam Veterans, especially those who were, in Cleland’s words, “wounded psychologically” and reluctant to seek help at regular VA medical facilities and benefits offices.

The Vet Centers got off to a strong start. During their first two years, they provided readjustment counseling to almost 90,000 Veterans of the Vietnam War era. After Cleland departed VA in 1981, the program nearly fell victim to newly elected President Ronald Reagan’s plans to slash government spending. However, Veterans organizations and supportive politicians rallied to the Vet Centers’ side.

Their intervention not only saved the program but also ensured its growth. Instead of eliminating its funding as first proposed, Congress increased the program’s budget and authorized the opening of 45 new centers. To provide better oversight, VA established a separate Readjustment Counseling Service under the Department of Medicine and Surgery. The service assumed responsibility for all Vet Centers nationwide.

By 1989, ten years after the launching of what was originally envisioned as a short-term program, the Vet Centers had become a permanent part of the VA health care system. Centers existed in all 50 states as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands, reaching over 100,000 Veterans and their families annually. More centers were added in the decades that followed, bringing the total to 300 by the time VA celebrated the 40th anniversary of the program in 2019. The program expanded in other ways, too. Recognizing the value of the Vet Center approach to readjustment counseling, Congress in the 1990s and early 2000s extended eligibility to all Veterans who served during periods of armed conflict.

Over the years, the centers have also broadened their scope to include such services as bereavement and military sexual trauma counseling and screening for traumatic brain injuries. In 2009, the program increased its geographic range through the acquisition of a fleet of Mobile Vet Centers. Resembling RVs, the custom-designed vehicles enable VA to reach Veterans in rural or remote locations. The Mobile Vet Centers are also regularly dispatched to community events, college campuses, military demobilization sites, and anywhere else large numbers of Veterans might be found.

Since the program’s inception, well over a million Veterans of all wars have walked through the doors of the centers in search of counseling, comfort, and closure. Among the many who turned to the program for assistance was none other than Max Cleland. Around 2015, Cleland learned that he was suffering from a serious heart problem. The diagnosis triggered panic attacks, prompting him to pay a visit to the Vet Center in Atlanta, Georgia. The group therapy sessions there helped him control his fears and return to work. He lived for another six years, secure in the knowledge that the Vet Centers he had championed decades earlier would continue to serve Veterans long after his passing.

By Katie Rories, Historian, Veterans Health Administration, and Jeffrey Seiken, Ph.D., Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

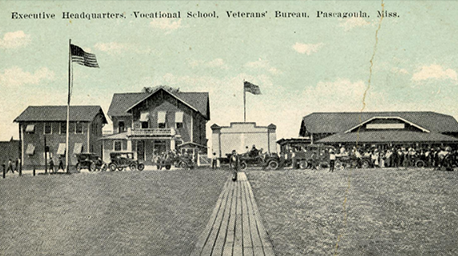

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.