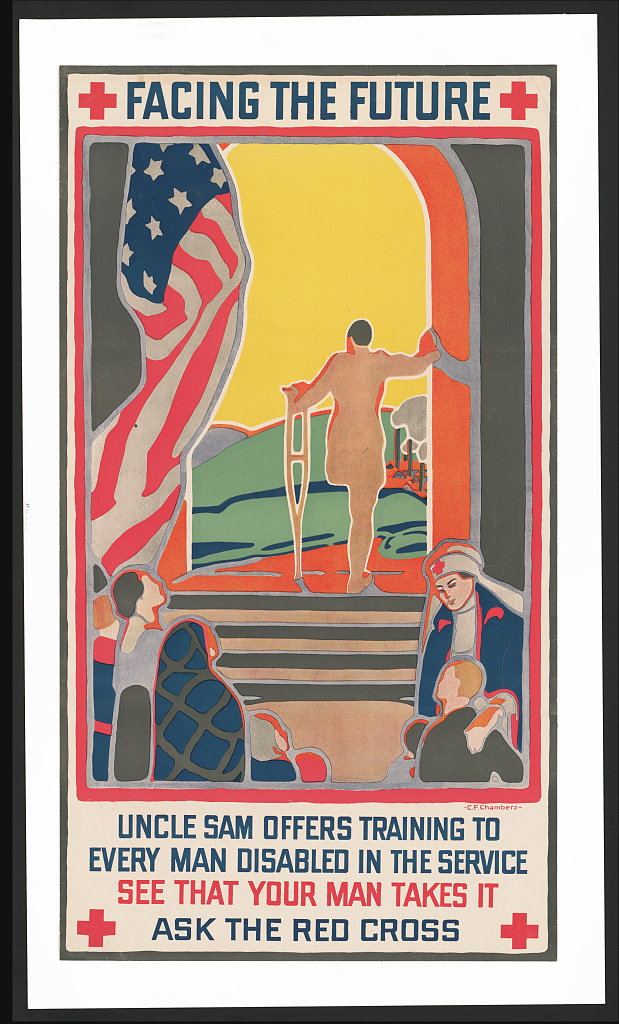

On November 29, 1918, shortly after World War I ended, President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed, “This nation has no more solemn obligation than healing the hurts of our wounded and restoring our disabled men to civil life and opportunity.” To fulfill the promise inherent in Wilson’s words, the government adopted a two-step approach to rehabilitating disabled Veterans. Step one entailed medical treatment accompanied by physical and occupational therapy in a hospital setting. Step two occurred on discharge from the hospital and consisted of federally funded vocational training.

The training offered to Great War Veterans assumed many forms, from apprenticeships and instruction in industrial trades to college courses and residential vocational schools run by the government. While varying widely in character, these programs were meant to serve a common purpose: help Veterans overcome their impairments, acquire new occupational skills, and find work. Once a disabled Veteran secured gainful employment, the government considered the person’s rehabilitative journey complete.

Vocational training was one of the benefits promised to service members in the omnibus War Risk Insurance Act passed by Congress in October 1917. The law, however, failed to specify how this training was to be delivered or by whom. At first, the Army’s Medical Department assumed responsibility for both stages of the rehabilitation process, medical and vocational. But the military soon found itself competing with the Federal Board for Vocational Education (FBVE) for control of the second phase. The board was a newcomer to the federal scene. Congress had established it in February 1917 to provide guidance and funding to state-level vocational programs for civilians in agriculture, industry, home economics, and various trades.

Army medical authorities and their allies in Congress lost their battle with the board. In June 1918, lawmakers approved an FBVE-sponsored bill known as the Smith-Sears or Vocational Rehabilitation Act that placed the board in charge of administering vocational training to disabled Veterans. The law divided Veterans into two categories. Section 2 of the act applied to Veterans with service-connected ailments that prevented them from resuming their pre-war occupations or finding a new one. The government covered the full costs of the training for these claimants and gave them a living stipend for the duration of their vocational program. Section 3 cases referred to Veterans with lesser disabilities who were still interested in pursuing a course of instruction. They were entitled to free training but no stipend. The law also required the board “to provide for the placement of rehabilitated persons” upon completion of their training “in suitable or gainful occupations.”

The FBVE’s lack of experience working with disabled Veterans placed it a disadvantage from the start. The board also possessed next to no institutional capacity in terms of facilities and instructors. Consequently, it had little choice but to rely on the private sector to provide the required training. The board contracted with over 1,600 trade schools, colleges, and other educational institutions. It also partnered with more than 8,000 shops, mills, factories, and businesses.

Its efforts produced very uneven results. Veterans complained that it took months for board officials to respond to inquiries and even longer to get placed in a training program, if at all. In February 1920, the New York Post reported that only 217 of the more than 100,000 Veterans eligible for vocational training had actually finished their programs and found employment through the board. The Post’s expose prompted the House Committee on Education to launch an investigation. The hearings lasted almost two months and brought to light more damning evidence about the board’s inefficiency and ineffectiveness.

The consolidation of all benefit programs for Great War Veterans into a new agency, the Veterans Bureau, in August 1921 effectively ended the board’s involvement in the rehabilitation of ex-service members. The Bureau’s first director, Charles R. Forbes, was determined to improve the vocational training services offered to Veterans and achieve better outcomes. He started by cleaning house, cancelling contracts with numerous schools and establishments that provided substandard training or engaged in fraudulent practices. He also assigned 3,000 employees to the Rehabilitation Division, where they worked exclusively on vocational training matters. Forbes made other changes, too, implementing more rigorous training standards and subjecting all vocational programs to close supervision.

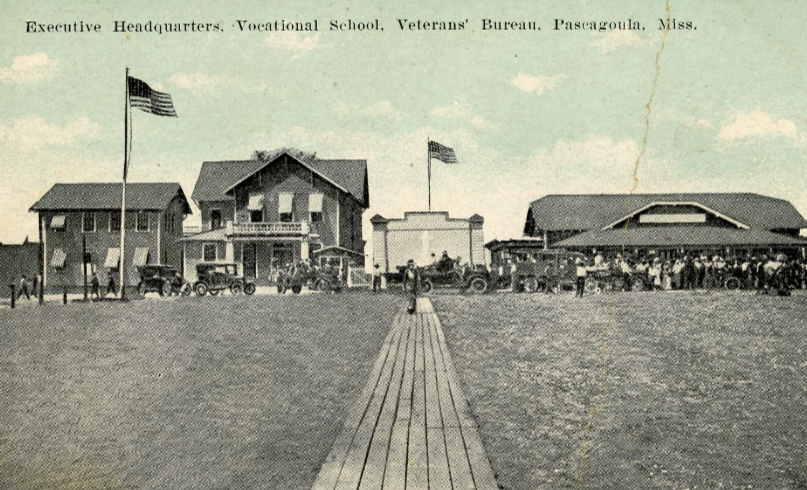

The Veterans Bureau did continue with one project begun by the FBVE: the establishment of dedicated residential vocational schools. The FBVE schools were designed primarily for Veterans with neuropsychiatric problems or inactive cases of tuberculosis who could not complete a traditional course of vocational instruction. The board opened eight such schools in the first half of 1921. Later the same year, the Veterans Bureau established a residential school in Chillicothe, Ohio, that offered courses in 18 different trades, including agriculture and beekeeping. The agency opened another four in 1922. But it soon abandoned the experiment due to the difficulty of keeping the schools funded, equipped, and staffed by qualified instructors. By mid-1925, all of the schools had been shuttered. The Veterans Bureau also closed the non-residential training centers it had been operating. Its annual report for 1925 ruefully stated, “It must be confessed that bureau schools did not prove the most effective facility for rehabilitation.”

Only about six percent of Veteran trainees at any given time attended these schools and centers. The vast majority enrolled in programs offered by the bureau’s partner trade schools, colleges, businesses, and other private entities. The 1925 annual report noted that the best results were achieved “when it was possible to place the trainee in a standardized course in a well-established institution.” Most Veterans chose a practical course of training in fields such as agriculture, manufacturing, and commerce that would equip them with marketable skills. But more than a few used the vocational benefit to pursue their ambitions in professional endeavors outside the worlds of business and industry. They studied acting, drawing, photography, music, and dozens of other subjects.

The Veterans Bureau ended all rehabilitation activities in 1928. In the ten years since the Vocational Rehabilitation Act became law, almost 180,000 disabled Veterans had entered vocational training and close to 130,000 finished it. Some 118,000 of the latter were Section 2 cases who received a living allowance in addition to tuition. These Veterans spent on average over two years enrolled in a program and approximately 97% were placed in a job upon completion.

Although it got off to a rocky start, the Vocational Rehabilitation Act was historic in its effects. For the first time, the government committed to retraining citizens disabled in wartime and returning them to work. For over 100,000 Great War Veterans, the government delivered on its commitment. The successful implementation of the 1918 law demonstrated the value of vocational rehabilitation and all but ensured that the benefit would be extended to Veterans of the next war.

By Jordan McIntire, Historian, Department of Veterans Affairs, and Jeffrey Seiken, PhD, Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 93: Occupational Therapy Floor Loom

During World War I and afterwards, the United States committed to rehabilitating sick and wounded soldiers so they could resume productive lives in the civilian workforce. The emerging field of occupational therapy played a crucial role in the rehabilitative process.