The massive mobilization of industry and manpower resulting from the United States’ entry into World War II lifted the nation out of the Great Depression and sent the economy soaring. But even as the country enjoyed new heights of economic prosperity, American leaders worried about what would happen after the war, once industrial output and government spending returned to peacetime levels. They feared the economy might fall into another tailspin, leading to widespread unemployment and social misery, especially for the millions of Veterans reentering the labor force.

Memories of World War I Veterans during the Great Depression sleeping on the streets, standing in breadlines, and marching on Washington, as 20,000 did in 1932, remained fresh in the public’s mind. This was a scenario that President Franklin D. Roosevelt, lawmakers on both sides of the political aisle, and members of the different Veterans organization wanted at all costs to avoid.

Roosevelt’s administration actually began planning for the aftermath of the war before the United States even joined the conflict. In late 1940, a full year before the attack on Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt asked the small team of government and academic experts on the National Resources Planning Board to study the problem of postwar demobilization as part of a broader investigation into a range of social and economic issues. In 1942, Roosevelt formed two separate committees to focus specifically on programs to assist returning Veterans.

By 1943, informed by the committees’ recommendations, Roosevelt’s own thinking on the issue had crystallized. Starting with one of his famed fireside chats in July 1943 and continuing in speeches delivered later in the year, he presented his vision of how the government should help Veterans find their footing and realize their potential following their discharge from the military. “We have taught our youth how to wage war; we must also teach them how to live useful and happy lives in freedom, justice, and decency,” he informed Congress. To this end, he called on lawmakers to provide Veterans with mustering-out pay, unemployment insurance, quality medical and hospital care, and support for higher education and job training.

By the end of 1943, numerous bills containing parts and pieces of the president’s plan were circulating in Congress. It was at this juncture that the American Legion entered the legislative fray. Founded in 1919, the Legion had established itself as the largest and most influential Veterans organization in the nation, with more than a million members nationwide and overseas.

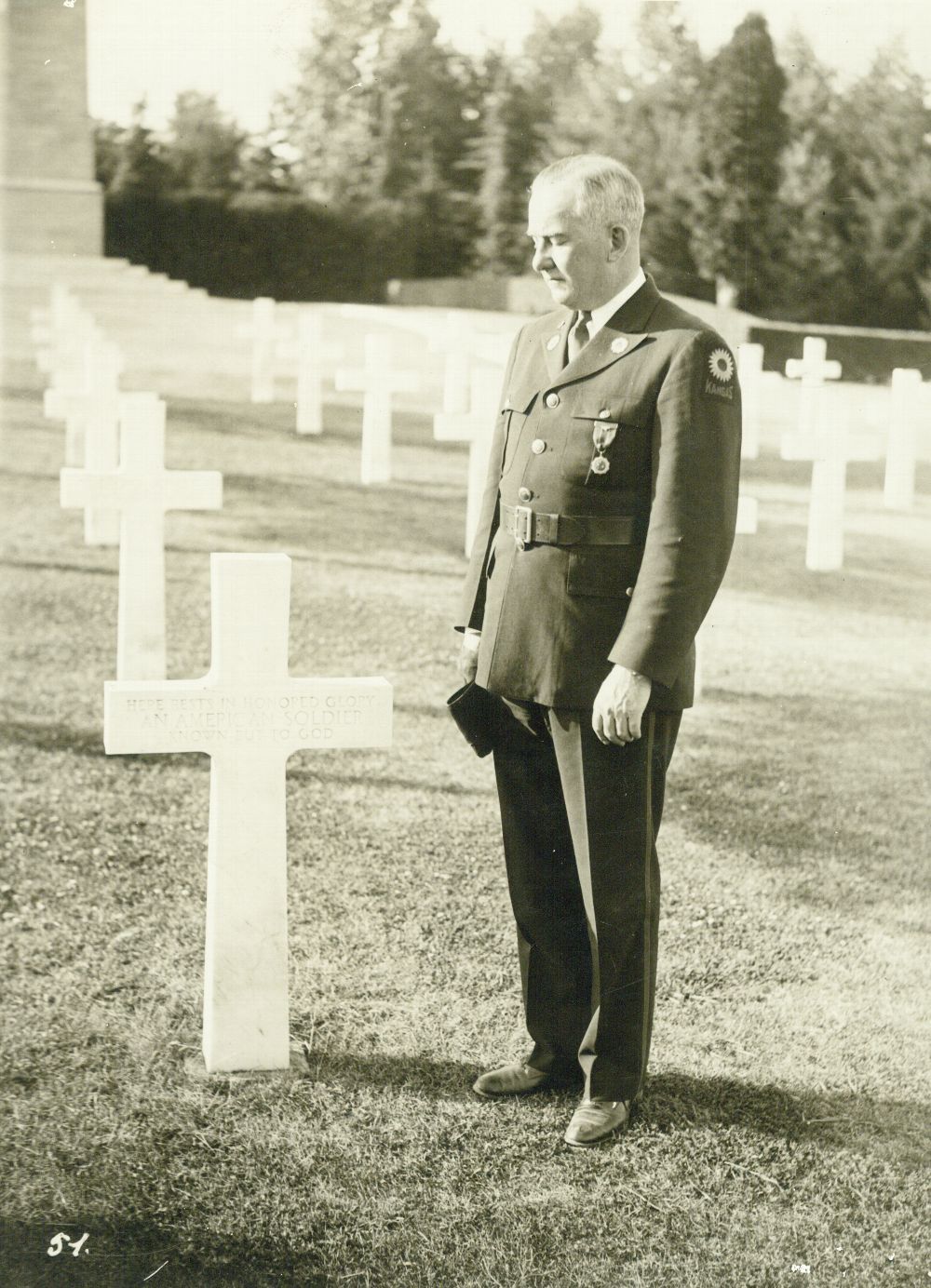

In late November 1943, the national commander of the Legion, Warren H. Atherton, assembled a committee composed of some of the organization’s most distinguished members to prepare a bill for Congress. John H. Stelle, a staunch Roosevelt supporter who had served briefly as governor of Illinois, chaired the panel. Harry W. Colmery, a World War I Veteran, prominent lawyer, and former Legion national commander, also joined after receiving a letter from Atherton asking him “to serve on a committee which will have the most important job of this year.”

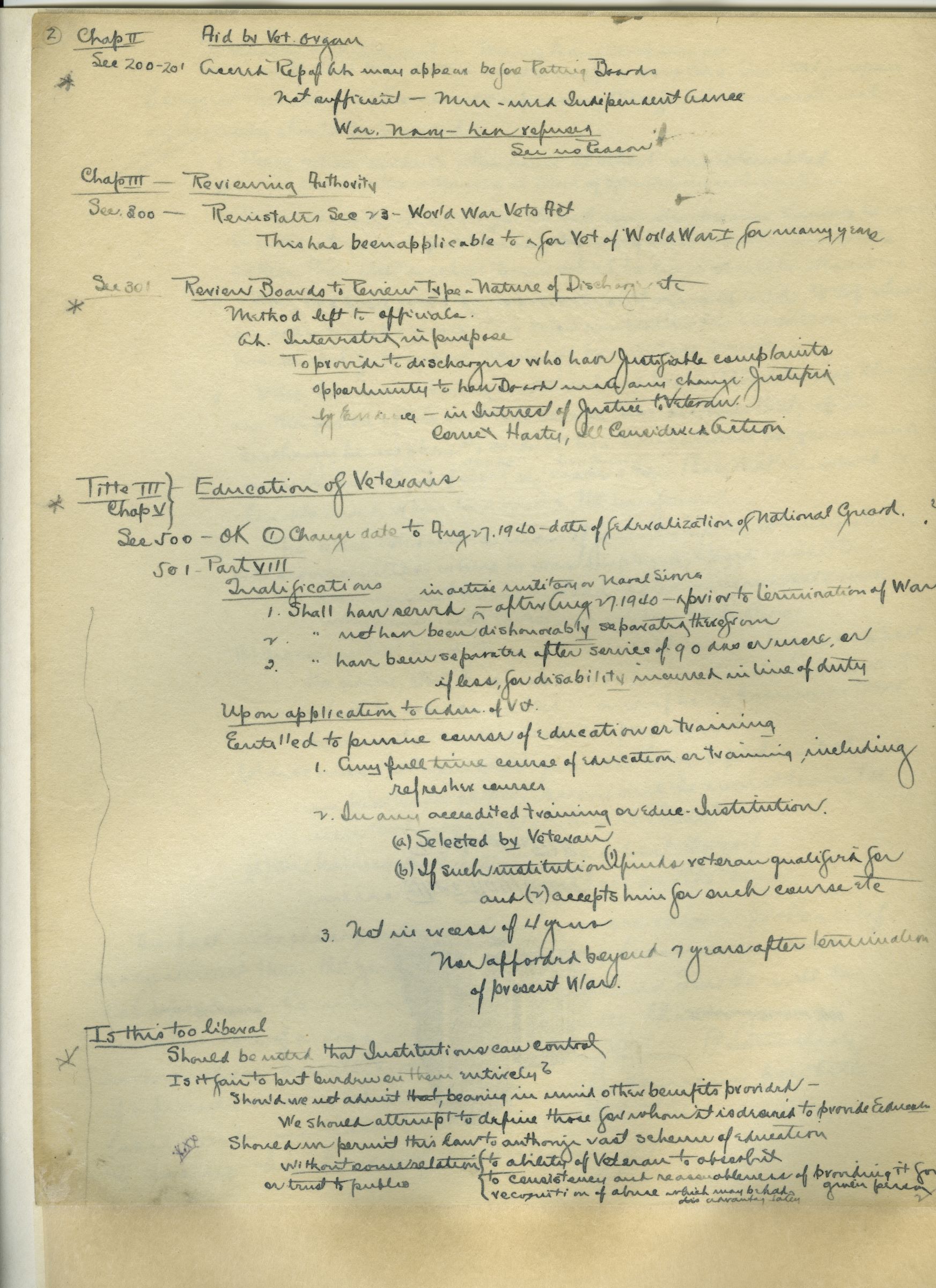

Stelle, Colmery, and the other committee members gathered in Washington, D.C., in mid-December and went to work. Over a frenzied three weeks, they collected information and interviewed government and private sector authorities in banking, education, employment, and other fields. They also debated among themselves what should go into the bill and how it should be structured. Colmery took on the task of translating the mass of data and the group’s internal deliberations into concrete legislative language. Chairman Stelle would later credit Colmery with “[jelling] all of our ideas into words.”

He holed up in the Mayflower Hotel during the long winter evenings, sometimes working through the night. He wrote out a rough sketch of the bill in long hand on the hotel’s stationary. After revising the initial draft, the committee on January 8, 1944, felt ready to present its work to Congress, the president, and the public. In an inspired bit of branding, the Legion’s acting director of public relations, Jack Cejnar, came up with memorable name for the bill. He dubbed it “the G.I. Bill of Rights.”

The Legion bill incorporated the main elements of Roosevelt’s proposals—most notably, unemployment compensation and educational assistance— while adding several important new provisions, all rolled up into a single piece of legislation. The most significant of these new measures was a mechanism for the government to guarantee loans to help Veterans purchase a house, farm, or business.

The bill also stipulated that all benefits were to be managed by the Veterans Administration to ensure that Veterans did not have to contend with multiple government agencies as had been the case after World War I. The bill was introduced in Congress on January 10 and 11. A few days later, Atherton and Stelle met with Roosevelt for 45 minutes at the White House to brief the president on the bill’s features.

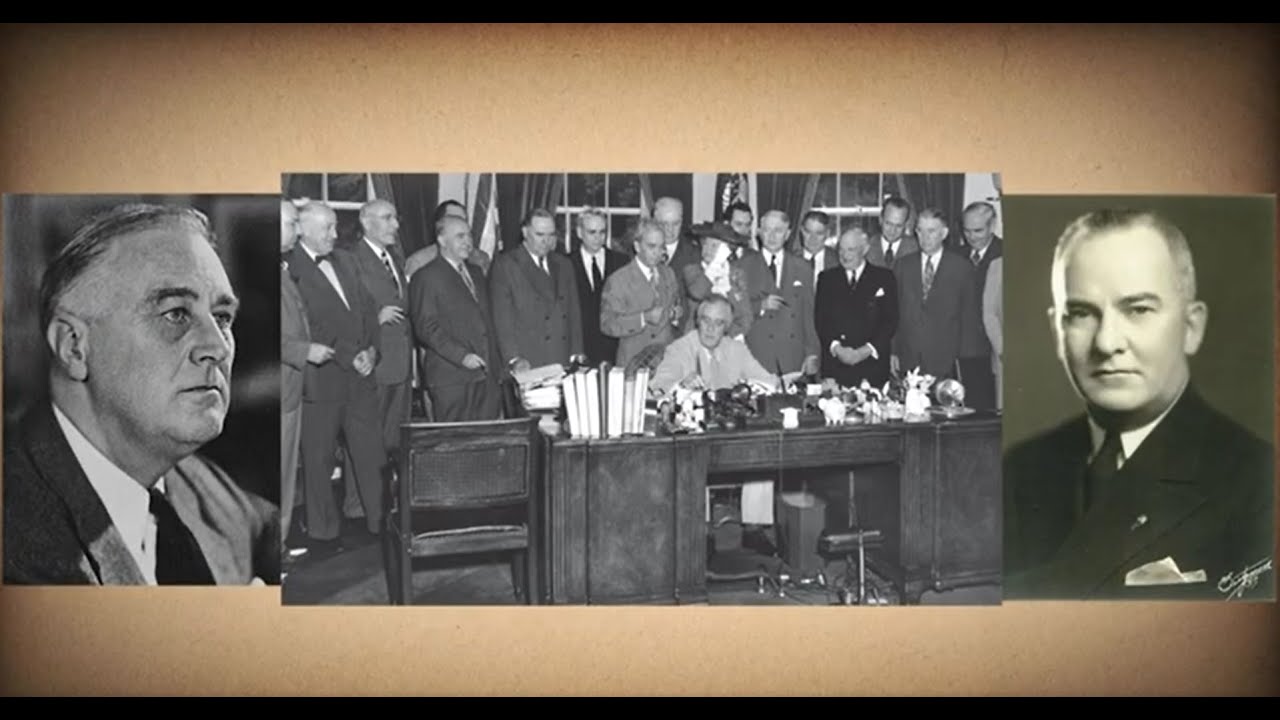

The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, as the G.I. Bill was officially designated, underwent many changes as it made its way through the House and Senate but the finished product was still recognizably the Legion’s handiwork. Fittingly, the organization was well represented when President Roosevelt signed the bill on June 22, 1944. Stelle and Colmery were among the Legionnaires in attendance at the invitation of the White House.

In a statement released the same day, Roosevelt celebrated the significance of what it meant for the G.I. Bill to become law: “With the signing of this bill a well-rounded program of special veterans’ benefits is nearly completed. It gives emphatic notice to the men and women in our armed forces that the American people do not intend to let them down.”

By Jeffrey Seiken, Ph.D.

Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.