In 2026, the United States will celebrate the 250th anniversary of its independence. While this will be the Department of Veterans Affairs’ first national centennial since becoming a cabinet-level department in 1989, its predecessor organizations, including the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, the Pension Bureau, the Veterans Bureau, and the Veterans Administration, routinely participated in national centennial commemorations. Each served to honor the contributions of American Veterans in preserving our freedom.

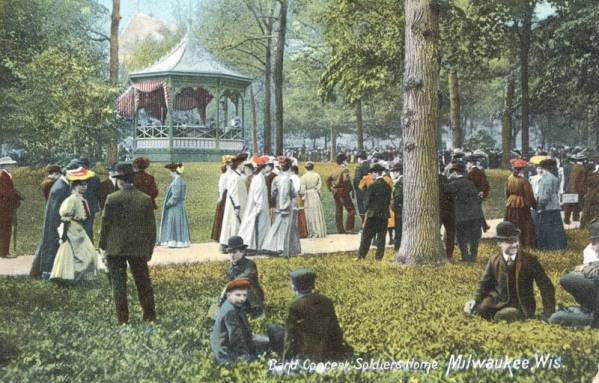

For the nation’s first centennial, thousands of Veterans celebrated the occasion at various branches of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. By 1876, the National Home had opened branches in Togus, Maine; Dayton, Ohio; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; and Hampton, Virginia. On the Fourth of July, the individual homes put on a series of events for both the Veterans in their care and the broader public.

The soldiers’ home in Milwaukee hosted an array of field games, two concerts by the Home Band, dancing, and a fireworks display.[1] Similar festivities took place at the soldiers’ home in Dayton, where 60,000 visitors traveled to celebrate the Fourth.[2] The day’s activities concluded with a “grand illumination” of approximately 18,000 tin lamps and numerous candles placed throughout the entirety of the grounds.[3] Spectators regarded it as the “finest [illumination] ever attempted in the West.”[4]

For the nation’s 150th anniversary in 1926, the Bureau of Pensions and the newly established Veterans Bureau each created exhibits for the Sesquicentennial International Exhibition in Philadelphia. The Veterans Bureau’s exhibit featured several hundred pieces of Veterans’ art, each of which were made by patients at Bureau hospitals. Accompanying the “strikingly illustrative” pieces was a series of case studies and charts demonstrating the available benefits Veterans could receive through the Bureau.[5]

Conversely, the Bureau of Pensions’ display highlighted the stories of those eligible for federal pensions, including the surviving widows of men who had served during the war of 1812. In their words, their exhibit served to “proclaim the nation’s gratitude for the suffering and sacrifice of the gallant soldiers and sailors who…cast their lives and fortunes on the altar of human freedom.”[6]

In 1930, the Pension Bureau, the Veterans Bureau, and the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers were combined to form the Veterans Administration. By the time of the nation’s bicentennial in 1976, VA was responsible for distributing benefits and medical care to over 29 million Veterans, or roughly 15% of the country’s population.

To give Veterans around the country the opportunity to participate, the agency’s Bicentennial Committee launched a national art contest for Veterans in VA hospitals, nursing homes, clinics, and other facilities. The theme of the contest, “Our Veterans: Defending America Over 200 Years,” encouraged participants to illustrate “the role Veterans have played over the past two centuries in protecting and preserving our nation’s ideals and freedoms.”[7]

In total, VA received 121 entries from Veteran artists, with the top 21 entrants receiving a cash prize. First Lady Betty Ford, who served as the competition’s honorary chairwoman, viewed the winning entries at the White House. Ten of the winning paintings were also put on display in the lobby of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C.[8]

Other bicentennial celebrations, contests, and displays took place at individual VA medical facilities throughout the nation. For example, patients at the local VA clinic in Knoxville, Iowa, planted 1,500 red, white and blue petunias to form the shape of the Liberty Bell and the numbers “76.”[9] In Augusta, Georgia, VA hospital employees put on a bicentennial-themed variety show for their patients, and received such acclaim that they were invited to perform at other celebrations in the area.[10]

Some former service members even incorporated centennial themes into their medical care. A disabled Veteran in Brockton, Massachusetts, created a Bennington flag as part of his rehabilitation treatment, while another VA patient in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, carved wooden models of VA’s bicentennial seal using the skills he learned in the hospital’s woodworking class. Other bicentennial activities included planting commemorative trees, creating floats for local parades, and burying time capsules.

Since 1876, centennial celebrations at VA and its predecessors have served to honor the contributions of servicemen and servicewomen in preserving our nation. VA looks forward to continuing this tradition during the nation’s semiquincentennial in 2026.

[1] “At the Soldier’s Home,” Daily Milwaukee News, July 4, 1876.

[2] “The Fourth was a Vast Success at the Soldiers’ Home,” Xenia Semi-Weekly Gazette (Xenia, OH), July 11, 1876.

[3] “The Centennial Fourth at the Soldiers’ Home,” Miami Helmet (Piqua, OH), July 20, 1876.

[4] “The Fourth was a Vast Success at the Soldiers’ Home.”

[5] E. L. Austin and Odell Hauser, The Sesqui-Centennial International Exposition: A Record Based on Official Data and Departmental Reports (Philadelphia: Current Publications, Inc., 1929), 119, https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Sesqui_centennial_International_Expo/W4dAAAAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=pensions.

[6] “Sesquicentennial Exhibit Featured Display of Veterans Programs,” VAnguard 22, no. 27 (June 29, 1976).

[7] “Bicentennial Art for Patients,” Bicentennial Bulletin 1, no. 2 (December 22, 1975), https://www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov/sites/default/files/pdf_documents/library/document/0067/1563282.pdf.

[8] “Winning Art at Kennedy Center,” VAnguard 22, no. 32 (September 7, 1976).

[9] “Knoxville Hospital Patients Grew a Bicentennial Bell in Living Color,” VAnguard 22, no. 32 (September 21, 1976).

[10] “Augusta Employees Mark Nation’s Birth,” VAnguard 22, no. 32 (September 7, 1976).

By Jordan McIntire

Historian, VA History Office

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

A Brief History of the Board of Veterans’ Appeals

On July 28, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6230 creating the Board of Veterans’ Appeals (BVA). The BVA was created as part of the Veterans Administration (VA), which had been established only three years earlier.

Featured Stories

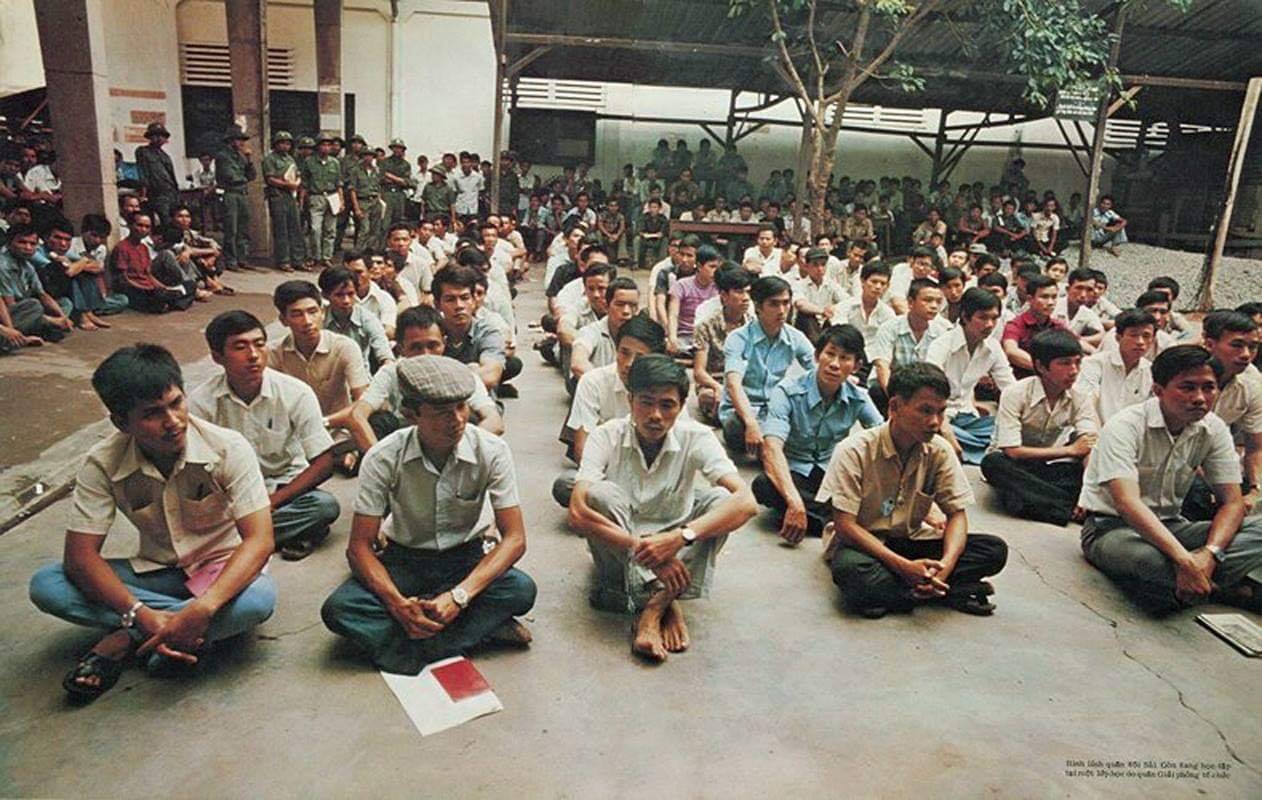

The Fall of Saigon 1975: A South Vietnamese Military Physician Remembers

"There was chaos in the streets when I made my way to the hospital on the morning of April 30, 1975. In a place of order, there was now great confusion. The director and vice director of the hospital were gone, making me, the chief of medicine, the highest-ranking medical officer."