History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 84: Gettysburg Address Tablet

President Abraham Lincoln is one of the most revered figures in American history. Rankings of U.S. presidents routinely place him at or near the top of the list. Lincoln is also held in high esteem at VA. His stirring call during his second inaugural address in 1865 to “care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan” embodies the nation’s promise to all who wear the uniform, a promise VA and its predecessor administrations have kept ever since the Civil War.

Ever since Lincoln first uttered those memorable words in November 1863, the Gettysburg Address has been linked to our national cemeteries. In 1908, Congress approved a plan to produce a standard Gettysburg Address tablet to be installed in all national cemeteries in time for the centennial of President Lincoln’s birth on February 12, 1909.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 83: First Liver Transplantation at VA Hospital

Prior to the 1960s, liver failure always ended in death. In May 1963, however, Dr. Thomas E. Starzl made medical history at the VA hospital in Denver, Colorado, when he performed the first liver transplantation on a patient who survived the operation.

Starzl's continued to refine his procedure, becoming a leading expert on liver transplants. The success rate for early transplants wasn't optimal, but that didn't stop him from researching new techniques and post-care practices. These innovations, coupled with new medications, improved the effectiveness and life-saving measures of that vital transplant surgery.

History of VA in 100 Objects

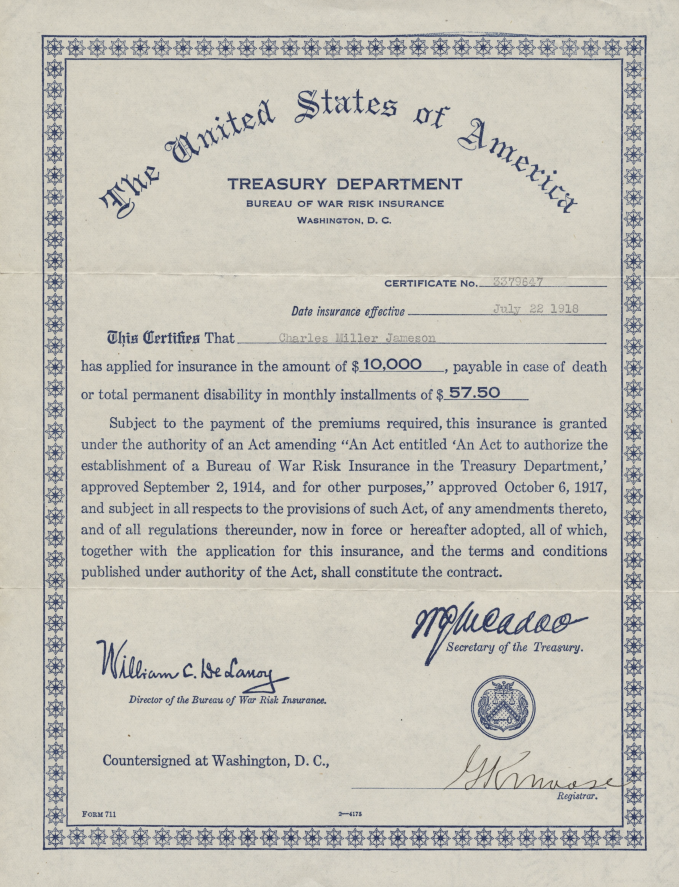

Object 81: World War I Insurance Certificate

An effort to remake the Veteran benefits system during World War I led to the 1917 War Risk Insurance Act that provided insurance benefits to Veterans well beyond their act of service was completed. A $10,000 policy could furnish the beneficiary a monthly income of over $57 in the early 20th Century.

It was a popular benefit, with 4 million applications before the end of the war. This program greatly impacted VA's future insurance efforts.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 80: LUKE/DEKA Prosthetic Arm

In the 19th century, the federal government left the manufacture and distribution of prosthetic limbs for disabled Veterans to private enterprise. The experience of fighting two world wars in the first half of the 20th century led to a reversal in this policy.

In the interwar era, first the Veterans Bureau and then the Veterans Administration assumed responsibility for providing replacement limbs and medical care to Veterans.

In recent decades, another federal agency, the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA), has joined VA as a supporter of cutting-edge research into artificial limb technology. DARPA’s efforts were spurred by the spike in traumatic injuries resulting from the emergence of improvised explosive devices as the insurgent’s weapon of choice in Iraq in 2003-04.

Out of that effort came the LUKE/DEKA prosthetic limb, named after the main character from "Star Wars."

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 79: VA Study of Former Prisoners of War

American prisoners of war from World War II, Korea, and Vietnam faced starvation, torture, forced labor, and other abuses at the hands of their captors. For those that returned home, their experiences in captivity often had long-lasting impacts on their physical and mental health. Over the decades, the U.S. government sought to address their specific needs through legislation conferring special benefits on former prisoners of war.

In 1978, five years after the United States withdrew the last of its combat troops from South Vietnam, Congress mandated VA carry out a thorough study of the disability and medical needs of former prisoners of war. In consultation with the Secretary of Defense, VA completed the study in 14 months and published its findings in early 1980. Like previous investigations in the 1950s, the study confirmed that former prisoners of war had higher rates of service-connected disabilities.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 78: French Cross at Cypress Hills National Cemetery in Brooklyn

In the waning days of World War I, French sailors from three visiting allied warships marched through New York in a Liberty Loan Parade. The timing was unfortunate as the second wave of the influenza pandemic was spreading in the U.S. By January, 25 of French sailors died from the virus.

These men were later buried at the Cypress Hills National Cemetery and later a 12-foot granite cross monument, the French Cross, was dedicated in 1920 on Armistice Day. This event later influenced changes to burial laws that opened up availability of allied service members and U.S. citizens who served in foreign armies in the war against Germany and Austrian empires.

History of VA in 100 Objects

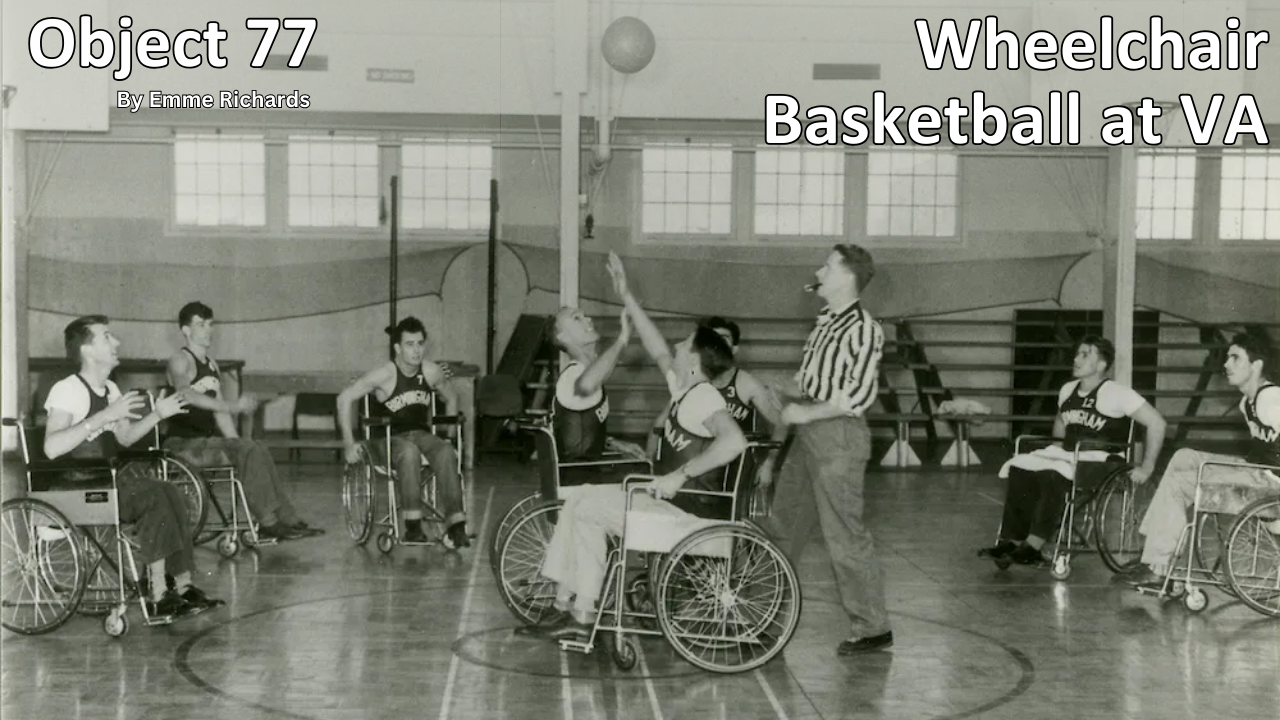

Object 77: Wheelchair Basketball at VA

Basketball is one of the most popular sports in the nation. However, for paraplegic Veterans after World War II it was impossible with the current equipment and wheelchairs at the time. While VA offered these Veterans a healthy dose of physical and occupational therapy as well as vocational training, patients craved something more. They wanted to return to the sports, like basketball, that they had grown up playing. Their wheelchairs, which were incredibly bulky and commonly weighed over 100 pounds limited play.

However, the revolutionary wheelchair design created in the late 1930s solved that problem. Their chairs featured lightweight aircraft tubing, rear wheels that were easy to propel, and front casters for pivoting. Weighing in at around 45 pounds, the sleek wheelchairs were ideal for sports, especially basketball with its smooth and flat playing surface. The mobility of paraplegic Veterans drastically increased as they mastered the use of the chair, and they soon began to roll themselves into VA hospital gyms to shoot baskets and play pickup games.

History of VA in 100 Objects

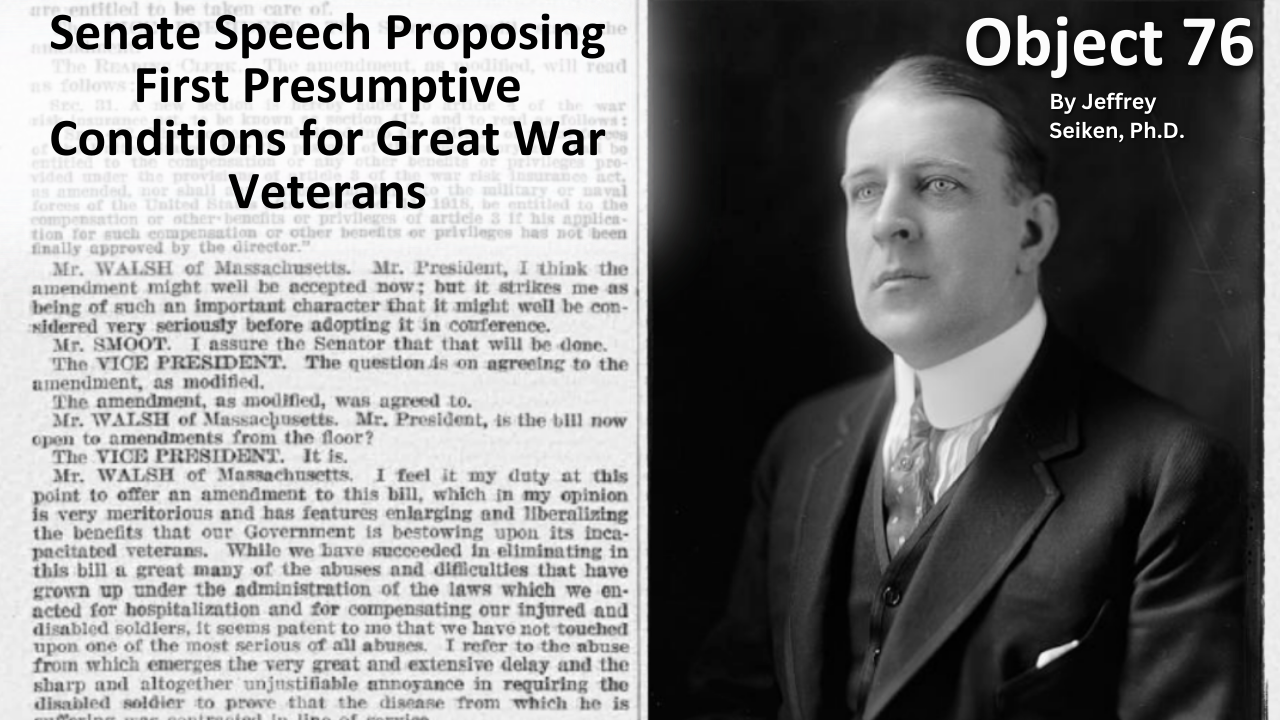

Object 76: Senate Speech Proposing First Presumptive Conditions For Great War Veterans

After World War I, claims for disability from discharged soldiers poured into the offices of the Bureau of War Risk Insurance, the federal agency responsible for evaluating them. By mid-1921, the bureau had awarded some amount of compensation to 337,000 Veterans. But another 258,000 had been denied benefits. Some of the men turned away were suffering from tuberculosis or neuropsychiatric disorders. These Veterans were often rebuffed not because bureau officials doubted the validity or seriousness of their ailments, but for a different reason: they could not prove their conditions were service connected.

Due to the delayed nature of the diseases, which could appear after service was completed, Massachusetts Senator David Walsh and VSOs pursued legislation to assist Veterans with their claims. Eventually this led to the first presumptive conditions for Veteran benefits.

History of VA in 100 Objects

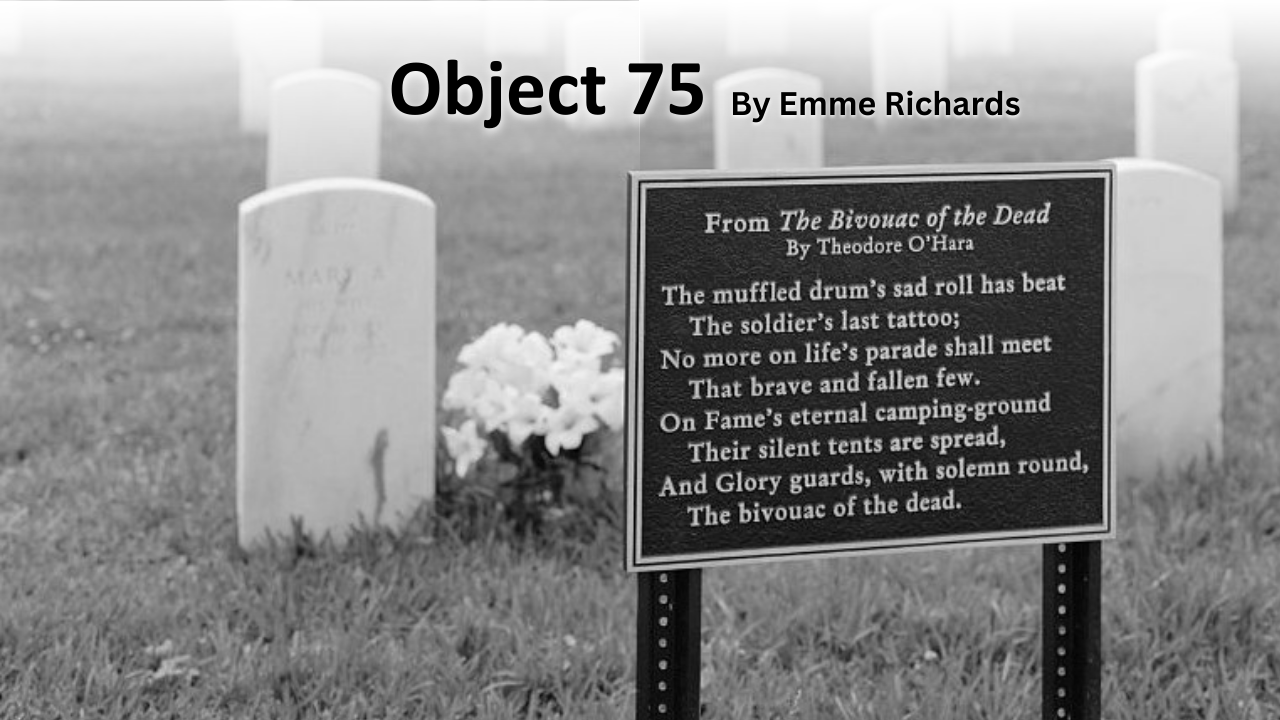

Object 75: “Bivouac of the Dead” Tablet

The mounted plaque stands in front of the headstones at Mobile National Cemetery in Alabama. The dark, cast-aluminum tablet draws a stark contrast to the sea of pearly marble beyond. Across its face in white lettering runs the sorrowful first stanza of Theodore O’Hara’ elegiac poem, “Bivouac of the Dead,” beginning with the verse “The muffled drum’s sad roll has beat / The Soldier’s last tattoo; / No more on life's parade shall meet / That brave and fallen few.” Tablets bearing passages from O’Hara’s poem can be found in dozens of VA national cemeteries across the country. Originally written to honor the Kentucky volunteers who died in the Mexican War (1846-48), the poem now serves as a literary memorial to all lives lost in service to the nation.

History of VA in 100 Objects

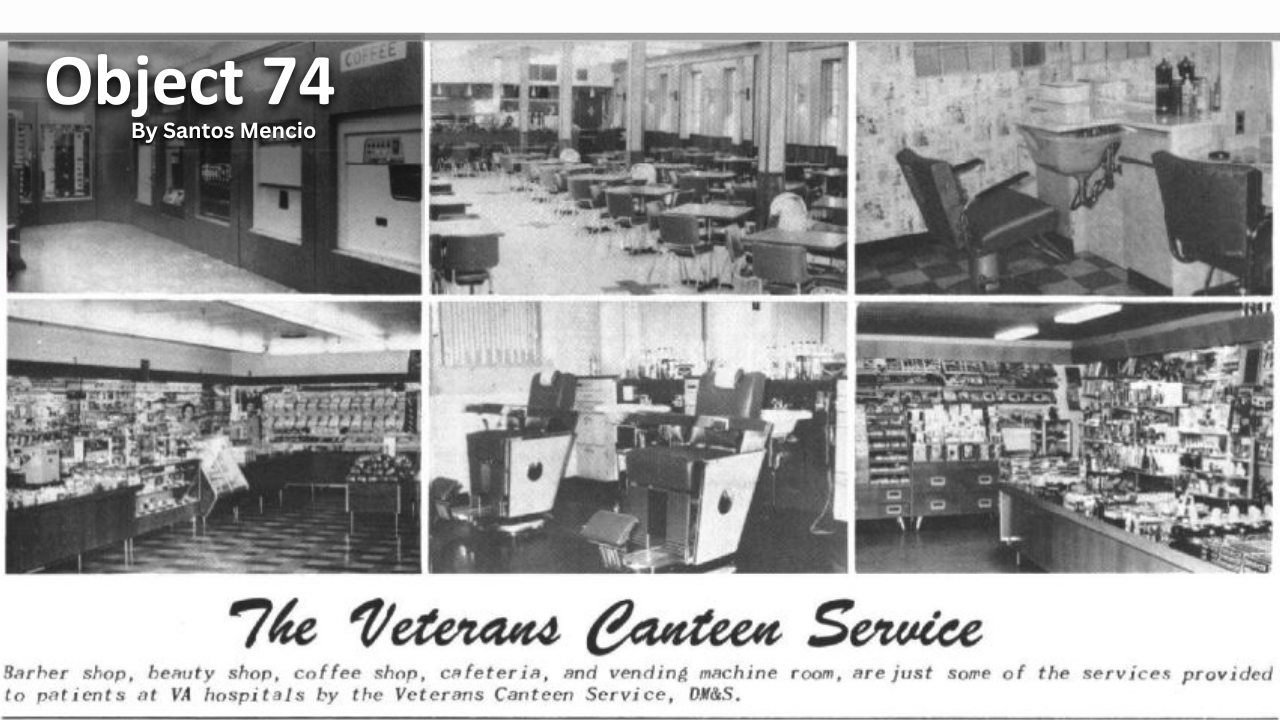

Object 74: Photo Spread on Veterans Canteen Service

When U.S. Army General Omar N. Bradley became head of VA at the end of World War II, he was determined to improve the quality of care across the agency’s hospital system. His commitment to providing better patient services extended to the stores and canteen service found in VA hospitals. Veterans and advocacy organizations complained that the concessions operated by third-party vendors often charged inflated prices and delivered substandard services.

After VA conducted an internal investigation that validated Veterans’ concerns, Bradley took the issue to Congress. His desire to find a better solution for Veterans led to the establishment of the Veterans Canteen Service.

History of VA in 100 Objects

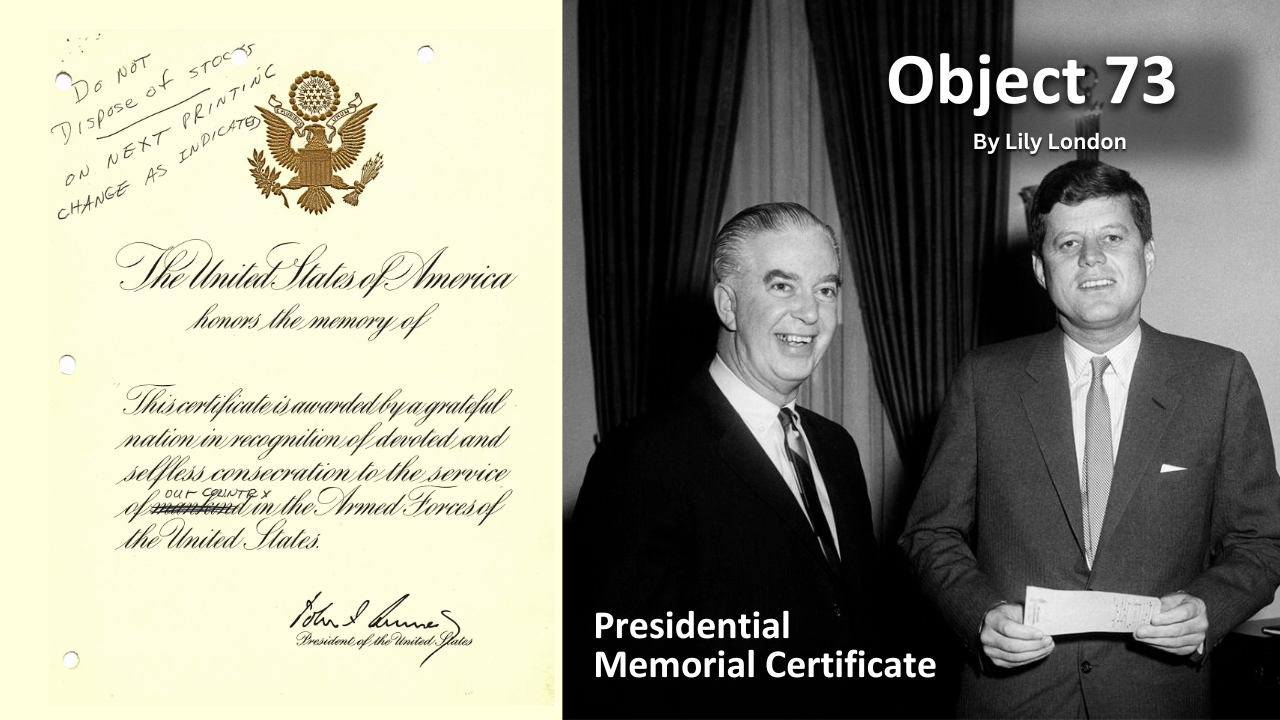

Object 73: Presidential Memorial Certificate

Just after New Year’s Day in 1962, World War II Army Veteran Benjamin B. Belfer sent a letter to his U.S. Senator, Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota, suggesting a simple yet powerful way for the government to honor deceased service members. The tradition was for family members to receive the folded American flag that had been draped over the Veteran’s casket during the funeral service. Belfer proposed presenting the next of kin with a memorial certificate signed by the president of the United States in addition to the burial flag. The certificate, he wrote, would be “a keepsake that will never be forgotten by the family and relatives and friends of the departed Veteran.”

After receiving Belfer’s letter Humphrey wasted no time in sharing his idea with the head of the Veterans Administration, John S. Gleason, Jr. Gleason also saw the value in the proposal and in mid-February his staff worked on creating a design for the certificate and wording. On March 6, the certificate was shown to President John F. Kennedy, Jr.. The following day, Kennedy sent Gleason a short note expressing his wholehearted approval. “I think it is an excellent idea, and I believe that the certificate is tastefully and appropriately done,” he wrote, adding that the issuing of certificates should begin “as quickly as possible.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 72: Central Blind Rehabilitation Center’s First Chief Welcomes First Trainee

On July 4, 1948, the Central Blind Rehabilitation Center at the Edward Hines, Jr., VA Hospital in Illinois admitted its first trainee. The Hines Center ushered in a new era of care for blinded Veterans. Yet, its opening was nearly three decades in the making.

Formalized federal care for blinded Veterans dates back to 1917, with the opening of Army General Hospital #7. Later the need to provide rehabilitative services to vision-impaired Veterans returned after World War II.

In 1948, VA opened the Central Blind Rehabilitation Center at the Hines VA Hospital outside of Chicago, Illinois. It's location was chosen because of the large Medical Rehabilitation department already in place was well-suited to provide oversight.