The search for the man in the medal

Some of our most exciting discoveries here at the National VA History Center come when we make a connection between the people and places who cared for Veterans in the past and those same places today. Luckily, our facility is headquartered on the grounds of the VA Medical Center in Dayton, Ohio, a campus where Veterans have received care for more than 150 years. Even with this heritage, it isn’t every day that you can just go outside and have big historic questions answered! Or is it?

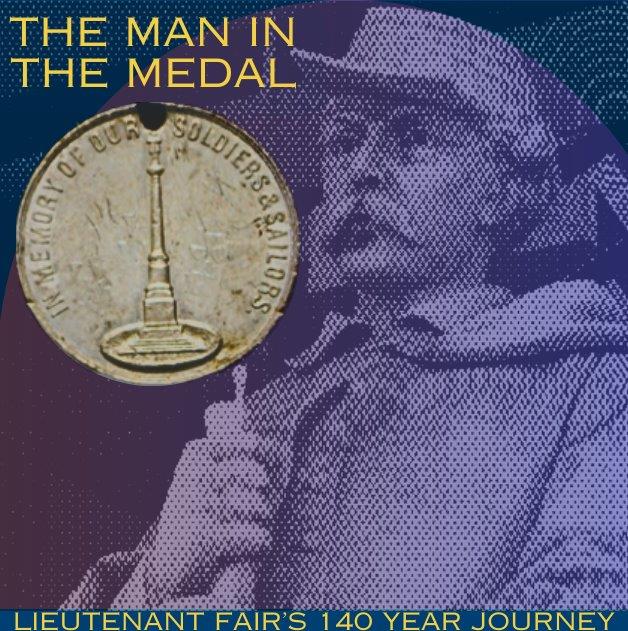

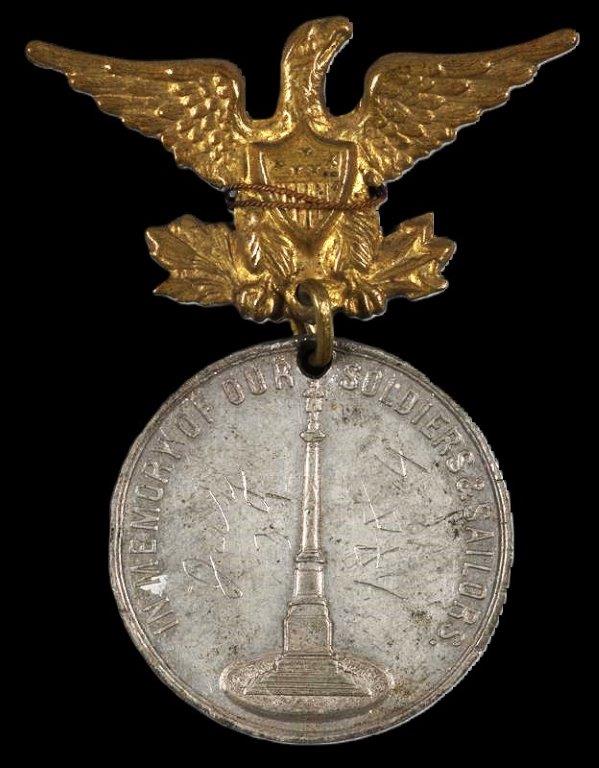

As the Collections Curator, I research historic objects to understand how they fit into the larger history of VA. One day, I was examining a small medal, only about 3 inches tall and an inch across (about the size of a half-dollar coin) with a small brassy eagle clipped to the top. The medal itself is engraved with the image of a tall column, topped with a soldier standing at rest. The text around it reads “In Memory of our Soldiers and Sailors.” On the back, more text reads “Unveiled at Dayton, Ohio, July 31, 1884.”

I originally thought this was an engraving of the soldier’s monument located in Dayton National Cemetery, which also features a soldier standing atop a tall column. But a quick walk from the History Center to the Cemetery revealed a critical difference between the monument on the medal and the one at the Cemetery.

The monument in the medal is missing the stylized Greek-inspired acanthus leaves that surround the top (or capital, to be technical) of the column that the Cemetery has. Furthermore, the monument on the medal was unveiled in 1884, a whole seven years after the one at the Cemetery was dedicated. So, this meant that the medal must be associated with another soldier’s monument somewhere in Dayton.

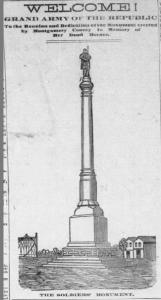

Since moving to Dayton last year, I have been walking all over the city. From my home in the Oregon District down to Riverscape Metropark, even all the way to the Dayton Art Institute. The more I looked at the medal, it was clear that I had seen the monument before. It was the Montgomery County Soldier’s Monument on the intersection of Monument Avenue and Main Street. At first, I thought it meant that this artifact didn’t have any link to Dayton’s historic Central Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers campus or the modern VA Medical Center at all. Once again, a short walk around the VA campus proved me wrong.

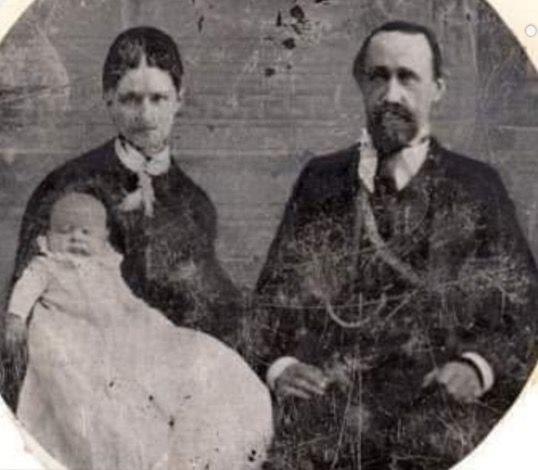

Standing in front of the medical center hospital is a tall, marble statue of a soldier. I had always assumed it was a scale version (or perhaps the original version) of the soldier at rest atop the monument at Dayton National Cemetery, but close observation showed me how wrong I was. A plaque in front of the marble soldier identifies him as George Washington Fair, a Veteran of the Civil War.

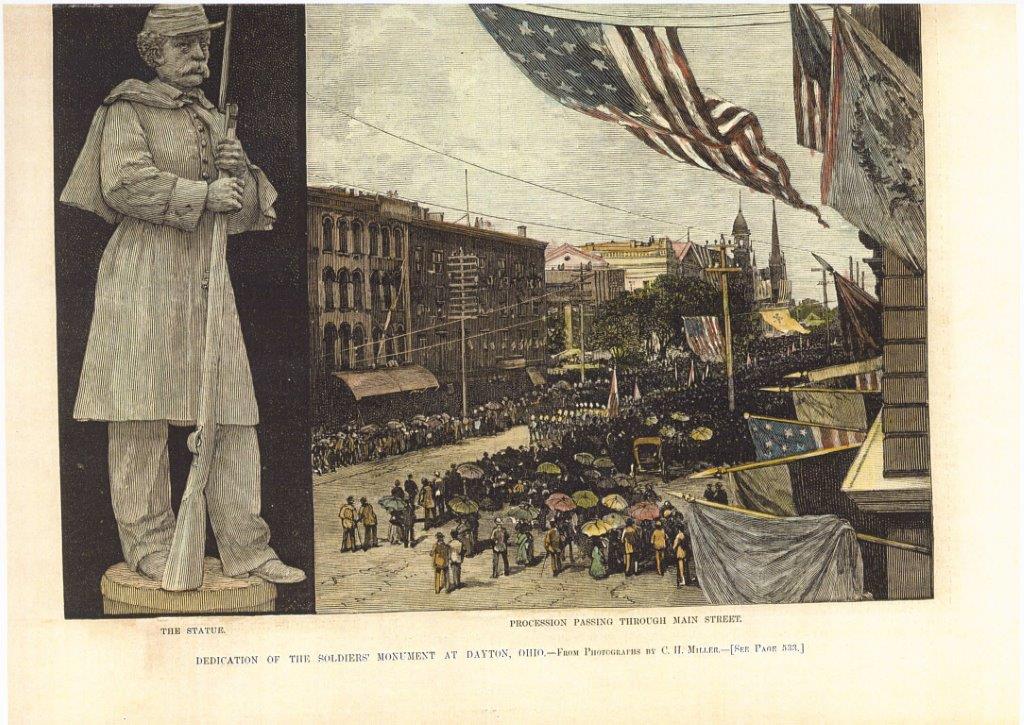

He joined the war as a Private in Illinois, then Ohio before being commissioned as 2nd Lt. during his time with Company D of the 10th Tennessee Infantry. After the war, Fair lived on West 5th Street in Dayton and worked as a bricklayer. It was there in 1883 where he was approached by two men from the County Commissioner’s Office. As the story goes, Montgomery County was the first county in the state of Ohio to use an 1881 law to levy taxes for the construction of monuments dedicated to the memory of Union soldiers. Initially, the Commissioner’s Office considered a statue of the Goddess of Liberty, which at the time was a common way to represent and personify the ideals of our nation. Many people disagreed with this plan, so the Commissioners set out to find a “broad shouldered, military-looking private soldier who met the ideals of the heroic sentinel” that they thought would serve as a better model for this memorial. That is how they ended up at George Fair’s door, and after some coaxing from his wife, he agreed to model for the sculpture.

Now the Commissioner’s Office had their model, and they needed to send photos of him to the sculptor in Italy as soon as possible. But if they wanted to display the “ideal private soldier,” they were going to need a uniform. Remember, the Civil War had been over for 18 years at this point, so how could the Commissioner’s office quickly acquire the full regalia of a Union soldier in Dayton Ohio? Lucky for them, the local branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers was just a short distance away.

The newspapers tell us that two men from the Commissioner’s office went to the Soldier’s Home and requested the Governor of the Home to supply them with a new uniform. It makes sense that they would have assumed they could get a uniform there, as all members of the National Homes were issued Union Army-styled uniforms. In fact, the Central Branch in Dayton was the central depot for uniforms for all the other homes around the country. We have several buttons that were originally part of these uniforms in the permanent collection of the National VA History Center, just like the ones that Lieutenant Fair would have had on his uniform when he posed for the photos. When George Fair met the men at a photography studio on Main Street, he donned the uniform (a No. 4, apparently the largest size available), belt, scabbard, cartridge box, held the musket, and pictures were taken that would be used for the sculpture.

This means that the man who has stood watch over Dayton for more than a century was not just wearing a Union soldiers’ uniform but was wearing the exact uniform worn by thousands of his disabled brothers-in-arms who lived in the National Homes. How fitting for a memorial to the soldiers of Montgomery County to have such a strong and unique connection to the Central Branch, one of the first institutions in our Nation’s history dedicated to the care of Veterans after their service.

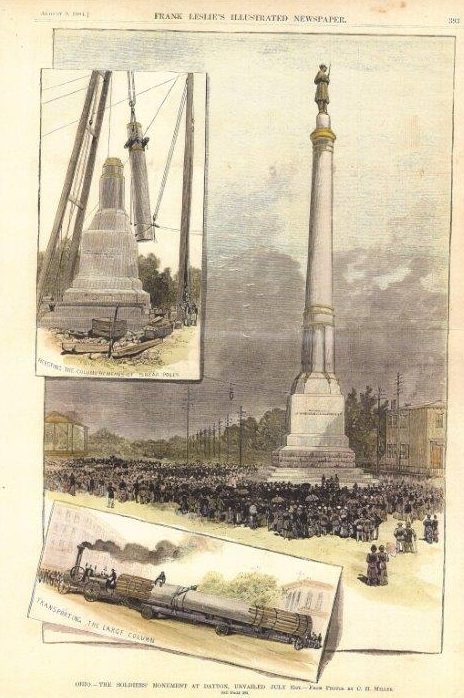

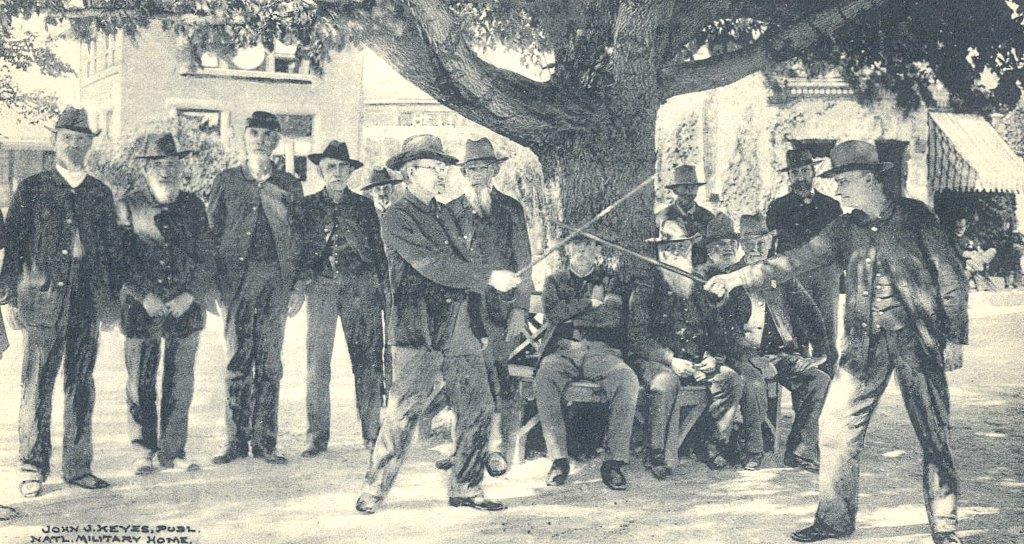

The Montgomery County Soldier’s Monument was unveiled to the public on July 31st, 1884, exactly 140 years ago this month. The grand reveal was the culmination of a three-day celebration of Union Veterans who had gathered in Dayton for a reunion. In total, the city may have seen more than 100,000 visitors for the event, including former president Rutherford B. Hayes, who gave a speech in front of the monument before its unveiling.

On that day, prior to the monument being dedicated, a change in weather dampened the cloth that covered the it. As a result, during the reveal to the people of Dayton, the rope was pulled, but nothing happened. Luckily, a well-known steeplejack (a craftsman who scales church steeples for maintenance and repair) was able to scale the column and unveil 2nd Lt. Fair to the world. As the story goes, he scaled the sculpture of the Veteran and sat on its shoulders, waving his hat to the people of Dayton below. The citizens were so thrilled with this hero of the day that once he returned to the street, they put him on their shoulders and paraded him around the square.

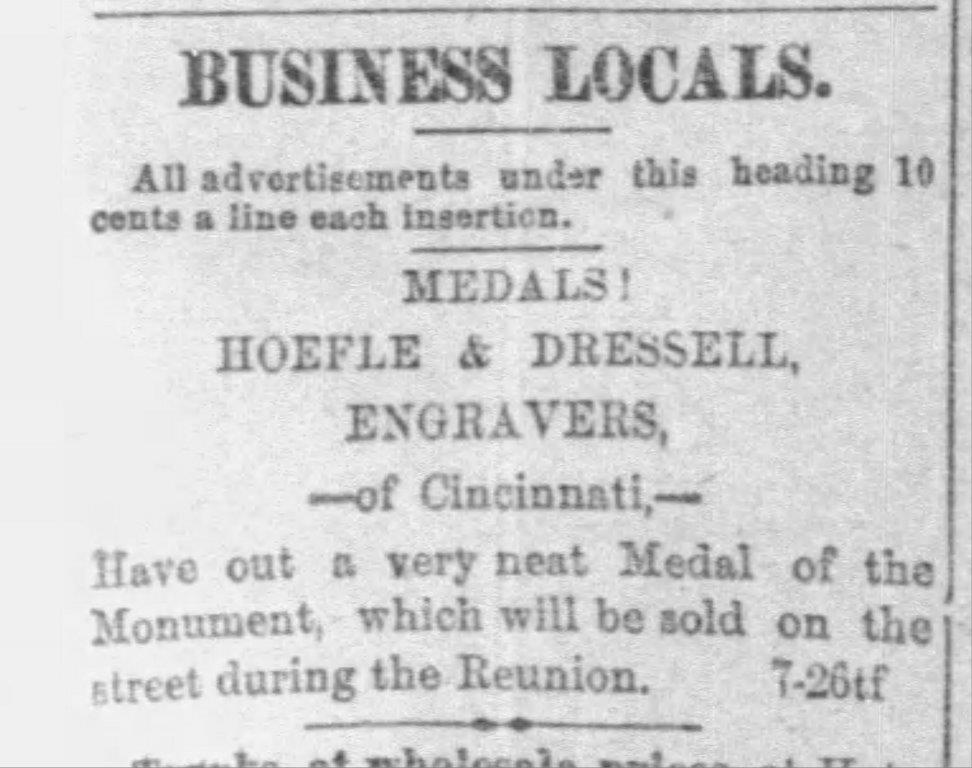

The newspapers captured the excitement out on the street leading up to and during the event, and even featured advertisements from local businesses who were preparing for the crowds that filled the streets.

This advertisement from The Dayton Herald tells us that “very neat” medals such as the one that ended up on my desk were sold by Hoefle & Dressell, engravers from nearby Cincinnati. We may never know who originally purchased this medal, or how it ended up at the Dayton VA over a century later, but it shows that even the most unlikely of artifacts carry big stories within them.

Even after the monument was unveiled and the festivities had ended, Fair’s journey was far from over. After spending 64 years at the intersection of Main Street and Monument Avenue, the monument was relocated in 1948 to Sunrise Park, near the end of the Veterans Memorial Bridge. He only stayed there for a short while, moving back to its original location downtown in 1991. After this move, the original marble statue was removed and used to cast a new statue out of bronze. Since then, the bronze version of Fair keeps watch at his original post in bustling Downtown Dayton, while his marble counterpart was given a new home.

In 1993, the original marble statue of Fair was rededicated on the grounds of the Dayton VA Medical Center. There it sits to this day, greeting the Veterans who come to the hospital for their medical care. The image of Fair has even been incorporated into the official logo of the Dayton VA, along with their motto “A Heritage of Healing.” Thanks to the research done at the National VA History Center, we can honor Fair’s 140-year journey to the Soldiers Home and back again as an essential part of that heritage.

Curator’s Note: We at the National VA History Center are aware that the individual named George Washington Fair was referred to as “Private Fair” for most of the time since the monument was unveiled 140 years ago. Through our research, we discovered that George Fair was commissioned as an officer and 2nd Lieutenant during his time in Tennessee, and his obituary, headstone and discharge papers which confirm this information.

By Gage Huey

Museum Collections Manager, National VA History Center

Share this story

Related Stories

Curator Corner

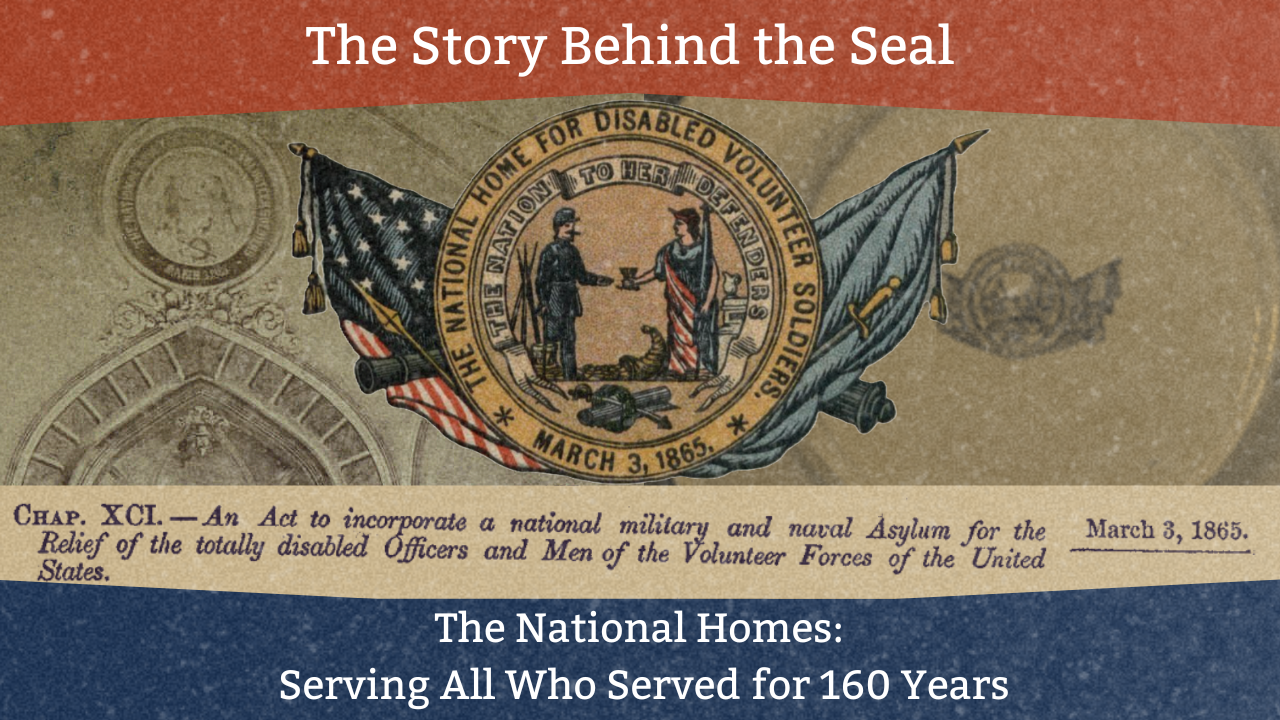

The Story Behind the National Homes’ Seal

The National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers turns 160 years old in 2025. The campuses are the oldest in the VA system, providing healthcare to Veterans to this day.

At the time of their establishment, they were the first of their type on this scale in the world. Within the NHDVS seal is the story that goes back 160 years ago.

Curator Corner

What’s in the Box? Fire Safety and Prevention at the National Homes

Fire safety may not be the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about Veteran care, but during the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers period (1865-1930), it was a critical concern. With campuses largely constructed of wooden-frame buildings, housing thousands of often elderly and disabled Veterans, the risk of fire was ever-present. Leaders of the National Homes were keenly aware of this danger, as reflected in their efforts to establish early fire safety protocols.

Throughout the late 19th century, the National Homes developed fire departments that were often staffed by Veteran residents, and the Central Branch in Dayton even had a steam fire engine. Maps from this era, produced by the Sanborn Map Company for fire insurance purposes, reveal detailed records of fire prevention equipment and strategies used at the Homes. These records provide us with a rare glimpse into evolving fire safety measures in the late 19th and early 20th Century, all part of a collective effort to ensure the well-being of the many Veterans living there.