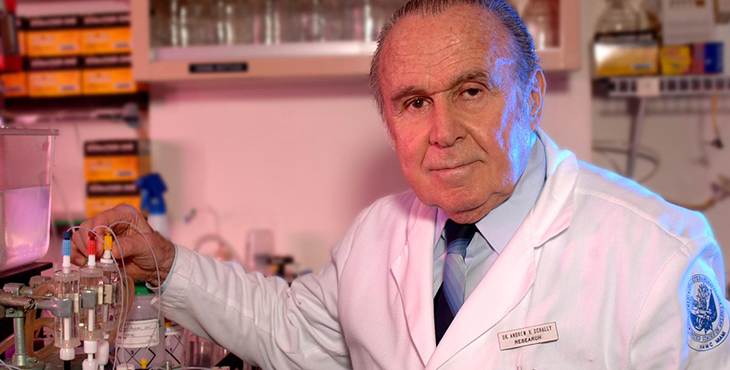

At a young age, Andrew Schally began exploring the possibility of a career in medical research. Born in Poland on November 30, 1926, Schally came from humble beginnings. Throughout the Second World War, Schally and his family lived within a Jewish-Polish community in Romania, enduring Nazi occupation in the region.1 Following the war, he began his lifelong journey into medical research by first studying in Scotland and England, before being admitted as a member of the National Institute of Medical Research Mill Hill of London in 1950 where he studied chemistry.”2

While working at Baylor University in the late 1950s, Schally began collaborating with the local Houston VA Hospital where he gained renown for his work with neuroendocrinology and gastroenterology. Seeing his research potential, the Veterans Administration decided to transfer him to the New Orleans VA Hospital where he became the chief researcher of the hypothalamus in 1962.3 This was also the year that Dr. Schally officially became a United States Citizen. At the same time, Schally was also a Professor of Medicine at Tulane University, highlighting the relationships the Veterans Administration formed with local medical schools to aid in research and discovery in the medical field.4 Fond of military history, Dr. Schally felt a great sense of honor in his new position as he worked to help Veterans.

Dr. Schally’s research primarily focused on the body’s production and effect of hormones. Specifically, Schally studied hormones released in the hypothalamus of the brain including thyrotropin-releasing hormones, lutenizing hormone-releasing hormones, and follicle-stimulating hormones.5

Ultimately, Dr. Schally concluded that the pituitary gland of the brain was under the control of the hypothalamus which regulates and releases particular hormones. Due to the relatively small quantities of these hormones within the pituitary, Dr. Schally and his combined VA-Tulane staff worked with a “large quantity of pig brains and lamb brains to uncover the structure of these hormones.6

In 1969, the team succeeded in isolating the pituitary hormone in question.7 As a result, they were able to reproduce this hormone chemically. This research had significant implications, marking a breakthrough in research surrounding contraception, diabetes, abnormal growth, mental retardation, as well as depression and other mental disorders.8

His research on the synthesis of hypothalamic hormones garnered Dr. Schally various honors and awards.9 In 1977, Dr. Schally along with collaborator Roger Guillemin received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for “their discoveries concerning the peptide hormone production of the brain.”10 This was the same year that fellow VA researcher, Dr. Rosalyn Yalow won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her work with radioimmunoassay.

Since his arrival in 1962, Dr. Schally has continued to serve our Nation’s Veterans through his dedication to medical research which still continues today. When asked to reflect on his career, he wrote, “I am deeply grateful to the Department of Veterans Affairs for allowing me to serve U.S. Veterans — and in fact, indirectly the whole nation.”11

Through research into “therapies for diseases, such as cancer” and other health issues, Dr. Schally’s work has had significant implications within the VA community and across the civilian population as a whole.

Footnotes

- “Andrew V. Schally – Biographical,” Nobel Prize, The Nobel Prize. ↩︎

- “Andrew Schally,” Jewish Virtual Library, Jewish Virtual Library. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “Tulane University’s Contributions to Health Sciences research and education: A Guide: Dr. Andrew V. Schally,” Subject Guides, Tulane University Libraries. ↩︎

- “Andrew V. Schally – Facts,” Nobel Prize, Nobel Prize Organization. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “Tulane University’s Contributions to Health Sciences research and education: A Guide: Dr. Andrew V. Schally,” Subject Guides, Tulane University Libraries. ↩︎

- “Dr. Schally Receives International Awards,” The Virginia Gazette (December 3, 1974). ↩︎

- “The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1977,” The Nobel Prize, Nobel Prize Organization. ↩︎

- Mitch Mirkin, “Reflections of a Nobel laureate in medicine on his career with VA,” VAntage Point, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. ↩︎

By Parker Beverly

VA History Office intern and Wake Forest undergraduate student

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

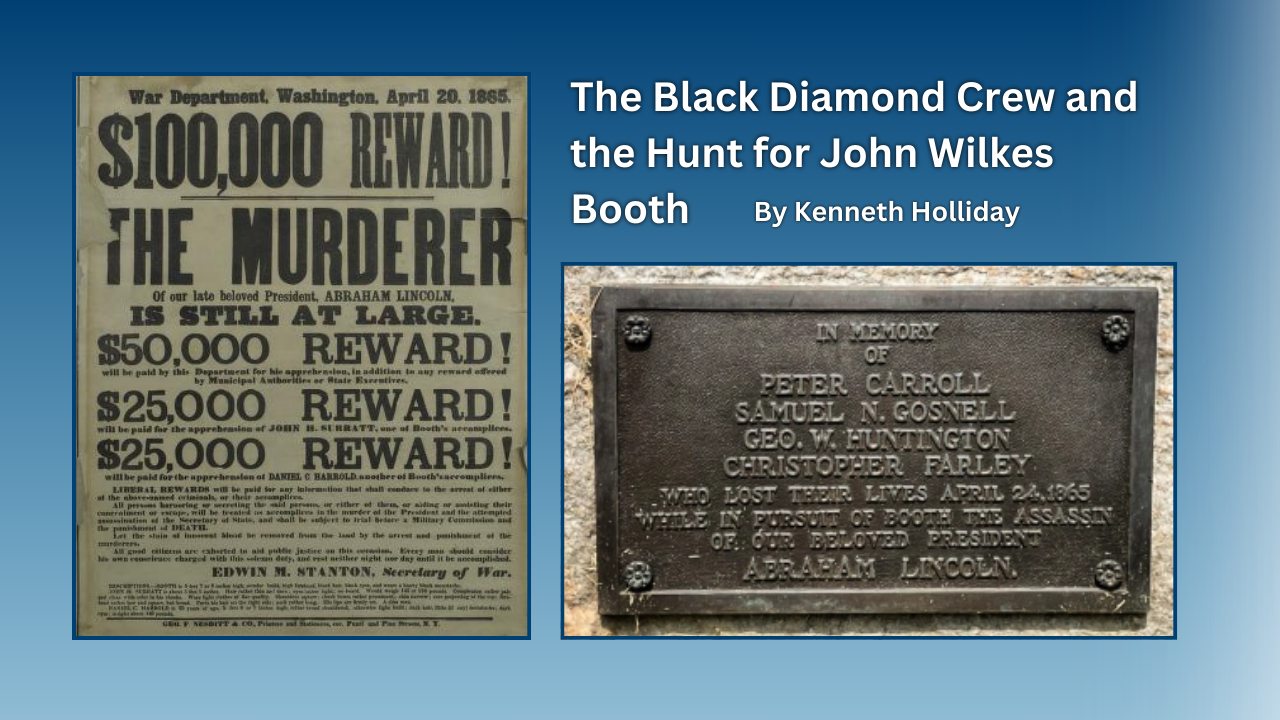

During the late evening, early hours of April 23-24, 1865, the Black Diamond, a ship on the Potomac River searching for President Abraham Lincoln's assassin John Wilkes Booth collided with another ship, the USS Massachusetts. The incident was a terrible accident during the frantic mission to locate the fleeing Booth before he escaped into Virginia. Unfortunately many lives were lost, including four civilians who had been summoned from a local fire department by the Army. For their assistance during this military operation, all four were buried in the Alexandria National Cemetery, some of the few civilians to receive that honor.

Featured Stories

In the mid-twentieth century, the lives of Dr. Ivy Brooks and Mildred Dixon, two trailblazing Black women physicians, converged at the Tuskegee, Alabama, VA Medical Center. Doctor's Ivy Roach Brooks and Mildred Kelly Dixon shared much in common. Both women were born in 1916 in the northeastern United States and received training in East Orange, New Jersey. They both launched careers in alternate medical professions before entering the fields of radiology and podiatry, respectively. Pioneering many “firsts” throughout their professional lives, both women faced and overcame the rampant racism and sexism of the era.

Featured Stories

After the United States entered World War I in 1917, American Expeditionary Force commander General John J. Pershing requested the recruitment of women telephone operators that were bi-lingual in English and French. Eventually 233 were selected out of over 10,000 applicants, and they served honorably through the war, earning the nickname of 'Hello Girls.'

However, their employment was not officially recognized as military service and therefore were neither honorably discharged, or eligible for the benefits other returning Veterans would receive. This kicked off a 60-year fight for 'Hello Girls' to receive legal Veteran status.