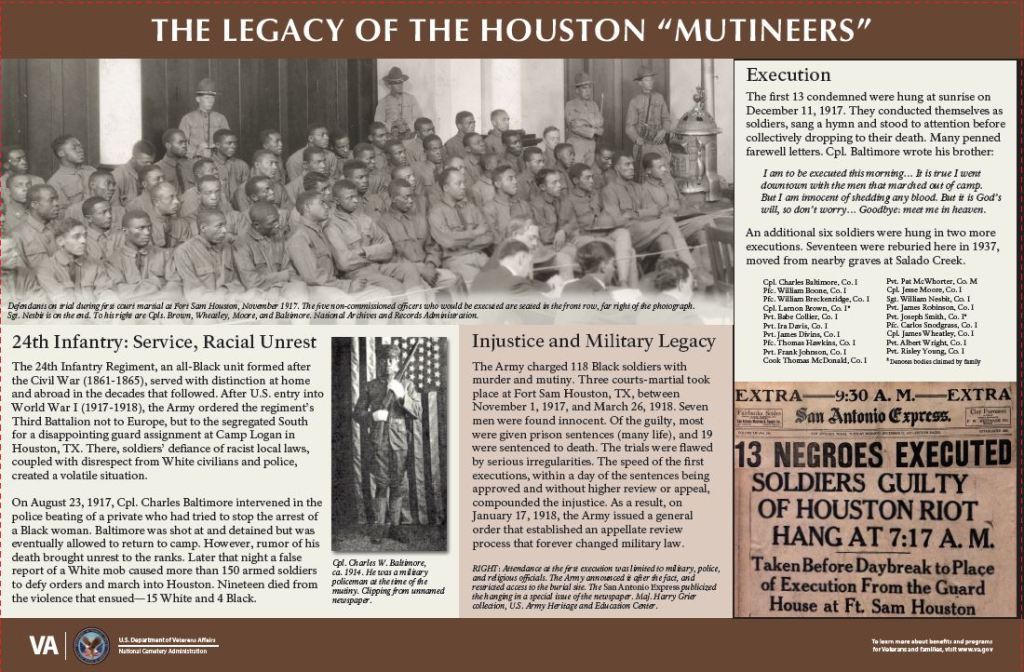

On February 22, 2022, the National Cemetery Administration (NCA) installed a wayside (or interpretive sign) at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery in San Antonio, Texas, near seventeen graves containing the remains of Black soldiers of the 3rd Battalion, 24th Infantry Regiment (3-24th) who died as a result of the largest mass execution of American soldiers by the U.S. Army.

On January 17, 1918 – as a result of flawed court martials and public response to immediate, secretive executions of these mutineers – the Army revised its appellate review process to require higher military review, forever changing military law. A group of NCA and Army officials, and descendants of one of the men executed, participated in the sign unveiling. The wayside installation is part of Black History Month recognition.

“I’m very pleased that NCA took this meaningful step toward recognizing an infamous and tragic event in American history,” said Deputy Secretary for Veterans Affairs Donald Remy. ”Future cemetery visitors will be enlightened by this display and come to understand the burdens under which Black soldiers served their nation. The treatment these Black soldiers received may have been legal by the standards of the day, but it wasn’t justice.”

On the night of August 23, 1917, following months of racist provocations, Black troops from the 3-24th stationed at Camp Logan in Houston took up arms and marched on the town. The ensuing violence left 19 persons dead: 15 White and 4 Black, some killings were intentional and others unintended in the chaos. Although Army officials concluded that consistent racist hostility by Houston citizenry and police contributed to the violence, the soldiers ultimately left camp against direct orders and were guilty of mutiny per the Articles of War.

The breaking point for Black soldiers happened when a respected non-commissioned officer who was serving as a 3-24th provost, Cpl. Charles Baltimore, intervened when he found Houston police beating a private who had interfered with the arrest of a Black woman. Police assaulted, shot at, and detained Baltimore. He soon returned to camp, but reports of his death brought unrest to the ranks. Rumors that night of a White mob caused at least one hundred soldiers to defy orders, take up arms, and march into Houston.

The 24th Infantry Regiment was one of four all-Black units formed after the Civil War (1861-1865) and in the decades that followed, the men served with distinction at home and abroad. After U.S. entry into World War I (1917-1918), the regiment’s Third Battalion (3-24th) was sent to the “Jim Crow” South to guard the construction of Camp Logan in July 1917.

Eleven years prior to the Houston event, an officer commanding Black troops of the 25th Infantry at Brownsville, Texas, wrote, “the sentiment in Texas is so hostile against colored troops that there is always the danger of serious trouble between the citizens and soldiers whenever they are brought into contact.” Soldiers’ defiance to local segregation laws, coupled with disrespect from White civilians and police, continued to maintain this volatile atmosphere.

The Army immediately determined all accused would face courts-martial under military jurisdiction, not civilian law as Houstonians desired. The 3-24th was immediately moved with the rest of its regiment by train to San Antonio.1 One hundred and eighteen Black soldiers were charged with disobedience of lawful orders, mutiny, assault with intent to commit murder, and murder. Three courts-martial took place at Fort Sam Houston’s Gift Chapel between November 1, 1917, and March 26, 1918. Ultimately, eight men were found innocent. Of the guilty, nineteen were executed and many more were sentenced to life in prison.

The trials were flawed by serious irregularities. The first thirteen condemned were hung at sunrise on December 11, 1917; in secrecy and within a day of sentencing, and without notifying higher authorities within the War Department. This first execution was decried by many as the equivalent of a federal lynching, and public outcries to President Woodrow Wilson led to the Army to implement an immediate regulatory change (War Department, General Orders No. 7) to the Articles of War.2

The change prohibited future executions without War Department review, and all military death sentences in the continental United States would require review by the president. The soldiers tried in the second and third courts-martial were able to seek review after their convictions. Of the sixteen soldiers sentenced to death in the second and third courts marital, President Wilson approved the execution of six and commuted the sentences of ten.

The remains of seventeen executed soldiers were reburied at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery in 1937, having been moved from their original graves at Salado Creek. The remains of two soldiers (denoted below) were returned to family by request. Graves of the executed are marked with standard government-issued General type, but are inscribed only with names and dates of death (Section PA, Graves 20-36):

- Cpl. Charles Baltimore, Co. I

- Pfc. William Boone, Co. I

- Pfc. William Breckenridge, Co. I

- Cpl. Larnon Brown, Co. I (body claimed by family)

- Pvt. Babe Collier, Co. I

- Pvt. Ira Davis, Co. I

- Pvt. James Divins, Co. I

- Pfc. Thomas Hawkins, Co. I

- Pvt. Frank Johnson, Co. I

- Cook Thomas McDonald, Co. I

- Pvt. Pat McWhorter, Co. M

- Cpl. Jesse Moore, Co. I

- Sgt. William Nesbit, Co. I

- Pvt. James Robinson, Co. I

- Pvt. Joseph Smith, Co. I (body claimed by family)

- Pfc. Carlos Snodgrass, Co. I

- Cpl. James Wheatley, Co. I

- Pvt. Albert Wright, Co. I

- Pvt. Risley Young, Co. I

The wayside panel, one of several NCA plans to install at its national cemeteries to interpret significant historic themes, presents visitors with the difficult story of Black World War I soldiers victimized by racial hostility, and how events in Houston altered military justice. Read more on the NCA History Program website (PDF, 11 pages).

Footnotes

- Brenner-Beck, Dru and John A. Haymond, “Clemency Petition – Returning the 24th Infantry Soldiers to the Colors” (November 15, 2020). ↩︎

- Haymond, John A., “Tempest in Texas: The Controversial Courts-Martial of an All-Black Regiment,” The Quarterly Journal of Military History (Spring 2021). ↩︎

Sources

- Haynes, Robert V., “The Houston Mutiny and Riot of 1917,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 76, No. 4 (Texas State Historical Association, 1973), 418-439.

- #137 – General orders / War Department, Adjutant General’s … 1918. – Full View | HathiTrust Digital Library

By Sara Amy Leach

Senior Historian, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

A Brief History of the Board of Veterans’ Appeals

On July 28, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6230 creating the Board of Veterans’ Appeals (BVA). The BVA was created as part of the Veterans Administration (VA), which had been established only three years earlier.

Featured Stories

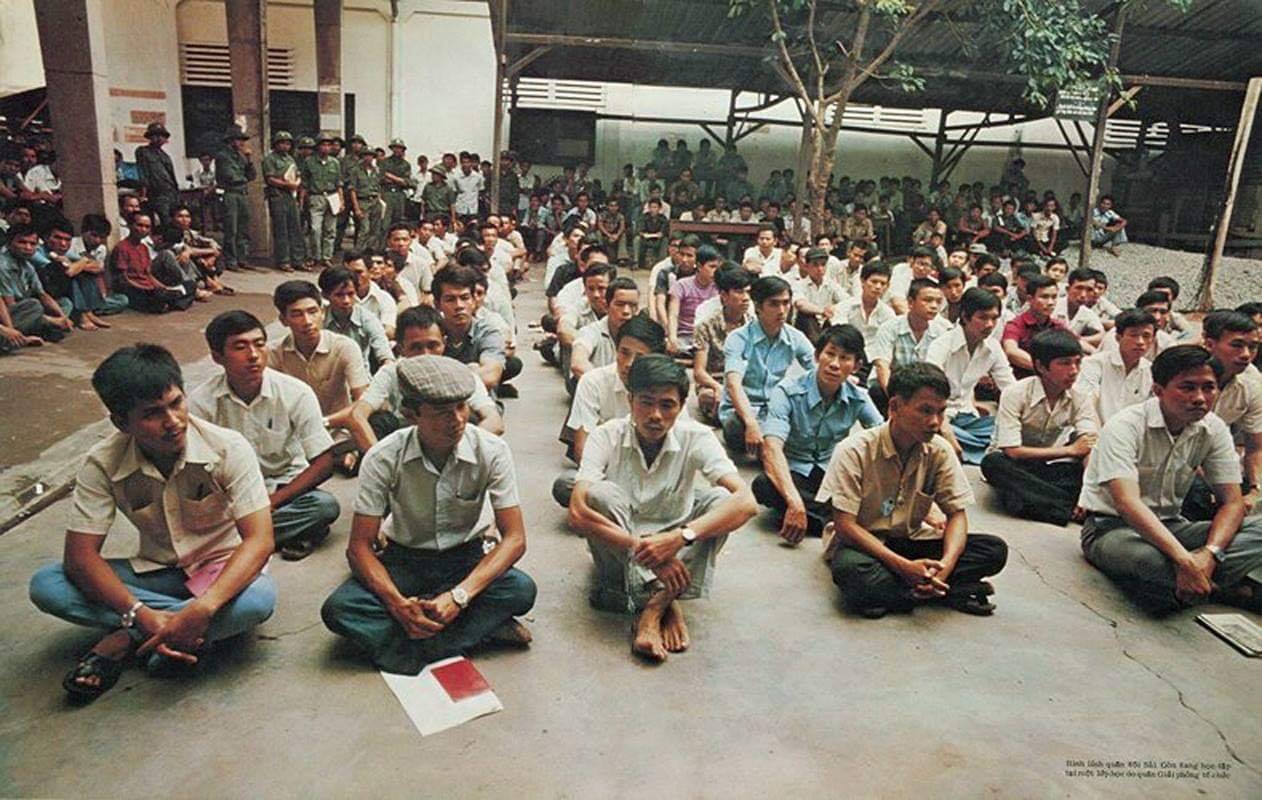

The Fall of Saigon 1975: A South Vietnamese Military Physician Remembers

"There was chaos in the streets when I made my way to the hospital on the morning of April 30, 1975. In a place of order, there was now great confusion. The director and vice director of the hospital were gone, making me, the chief of medicine, the highest-ranking medical officer."