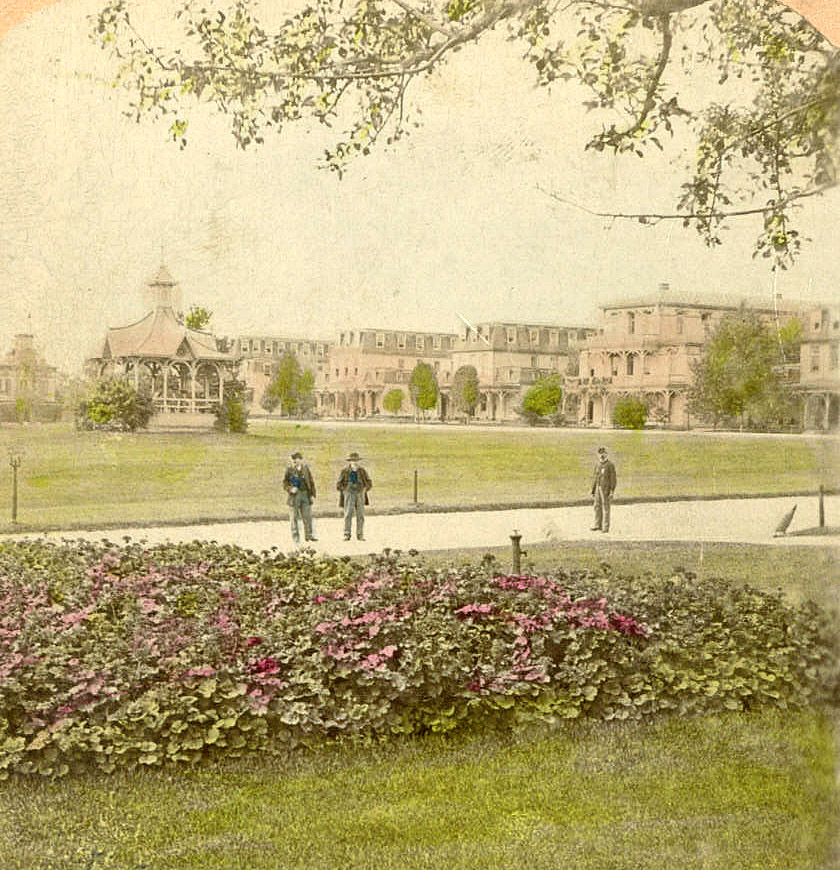

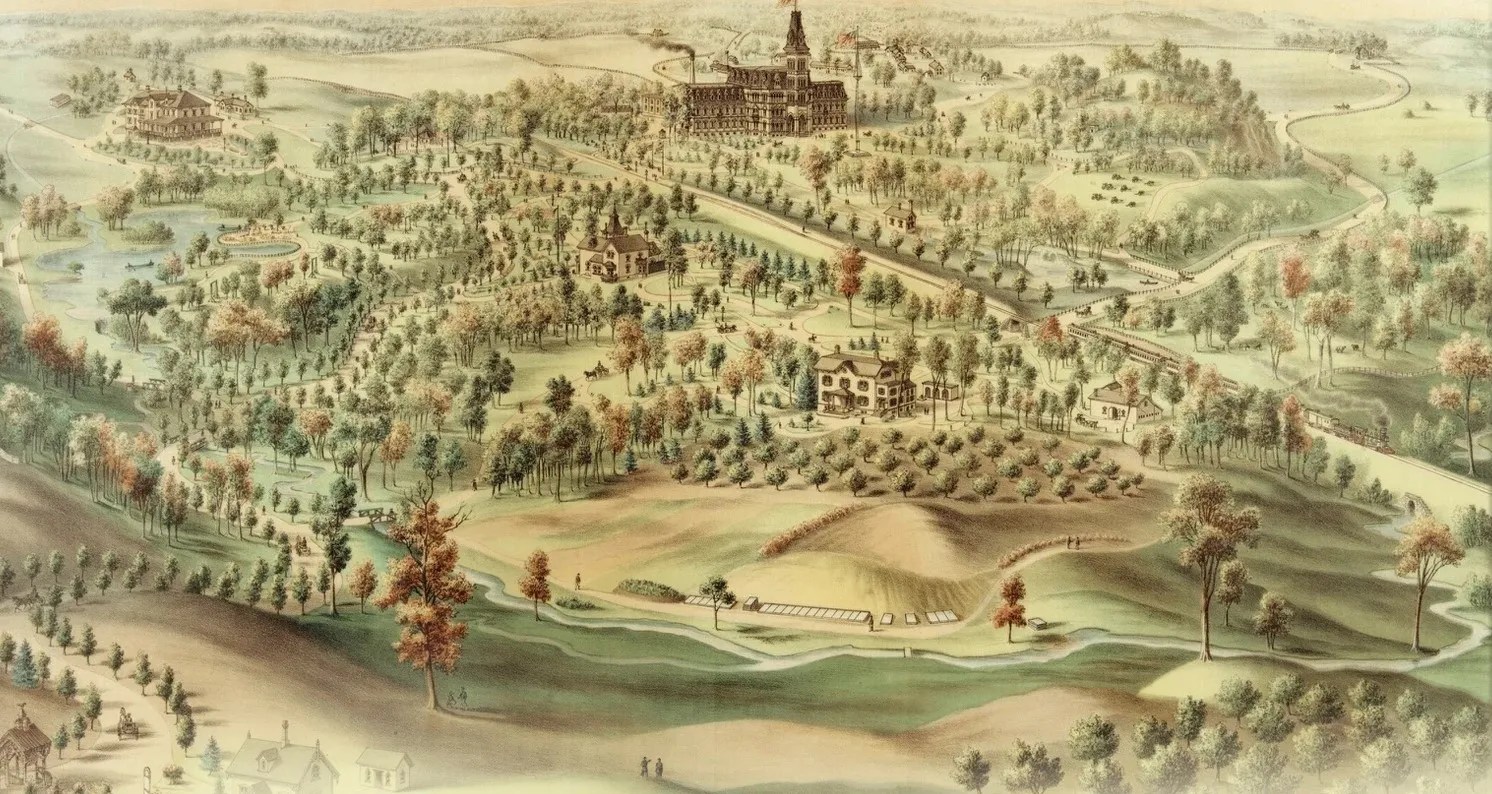

One hundred and forty-five years ago, on July 4, 1875, Civil War Veterans living at the Department of Veterans Affairs oldest facilities, the National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, were abuzz with anticipation as the day-long celebration of the nation’s Independence Day had finally arrived. It was a highlight of their year.

In 1875, only four National Homes had been established.1 These were located in Togus, Maine; Dayton, Ohio; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; and Hampton, Virginia. The U.S. flag contained 37 stars and Independence Day, or “the National Anniversary” as it was often referred, was the sole holiday that called for fun and frivolity, rather than somber contemplation. It provided the men a welcome break from their daily routines.

The following excerpt details the Fourth of July celebration held in 1875 at the Central Branch National Home (now Dayton VA Medical Center).2

Independence Day at the National Home began at sunrise with a national salute that “awakened the slumbering community of the glorious day they were to celebrate, and the universally interesting programme prepared by veterans for the enjoyment of all.” Buildings and grounds of the institution were dressed in bunting as flags floated from the tops of various buildings.

Railroad excursion trains to the National Home began at 6:00 a.m. and were filled to capacity for hours while roads were thronged in all directions with horses and carriages representing “one mass of humanity” coming to the Home for the day. The day’s events began at 8:00 a.m. with an entertaining show followed by a grand review (parade) of the veterans and dignitaries. When the review concluded, the Home Band led a huge procession to the cemetery where they played “’America’ in its sweetest strains,” followed by prayer and a speaker.

Afternoon festivities included outdoor sports and competitions of all varieties. A mule-race with a top prize of $5 kicked off the afternoon events which included “races for men on crutches and men in sacks, and men blindfolded with wheelbarrows to trundle… .” There were one-armed veterans who, having two good legs, made off with prize money by winning races. “The wheelbarrow race was one of the most amusing…veterans who propelled these implements were blindfolded. The barrows were to be wheeled against the flagstaff at the opposite limit from which the start was made… Of those who got the right direction, William Gleason, a blind man, struck his wheel against the staff and won the prize, $4.”

As the day marched on, clouds rolled in and threatened to ruin the evening fireworks display, but the Home’s Governor, Colonel Brown, was undeterred. He said, “The fireworks have been procured for the celebration of the Fourth, and that in spite of all the unfavorable influence outside they should accomplish just what was intended by their purchase. These old soldiers do not take stock in discouraging circumstances. They will not succumb to what other people consider impossibilities.” So, he had the fireworks hauled to the lake vicinity and up they went at the appointed hour. An eyewitness reported that “nothing so brilliant has ever been witnessed here.”

After the fireworks, the rush to get home was not easy. Trains were filled for hours and carriages clogged the roadways. At midnight, many visitors were compelled to walk home.

At the close of the day, it was believed that net proceeds from sales of gate tickets, refreshments, and sundry other items to visitors were sufficient to complete work on a monument on the grounds of the Home. “So that the celebration of the Home was a complete success in every respect.”

The article is based on a 2015 “VA History Tidbit” by Darlene Richardson, then the Veterans Health Administration Historian. Ms. Richardson retired from VA in 2019.

Note: This story was first posted on the VA Insider agency internal platform in 2020.

Footnotes

By Barbara Matos

Acting Program Specialist VA History Office

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

A Brief History of the Board of Veterans’ Appeals

On July 28, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6230 creating the Board of Veterans’ Appeals (BVA). The BVA was created as part of the Veterans Administration (VA), which had been established only three years earlier.

Featured Stories

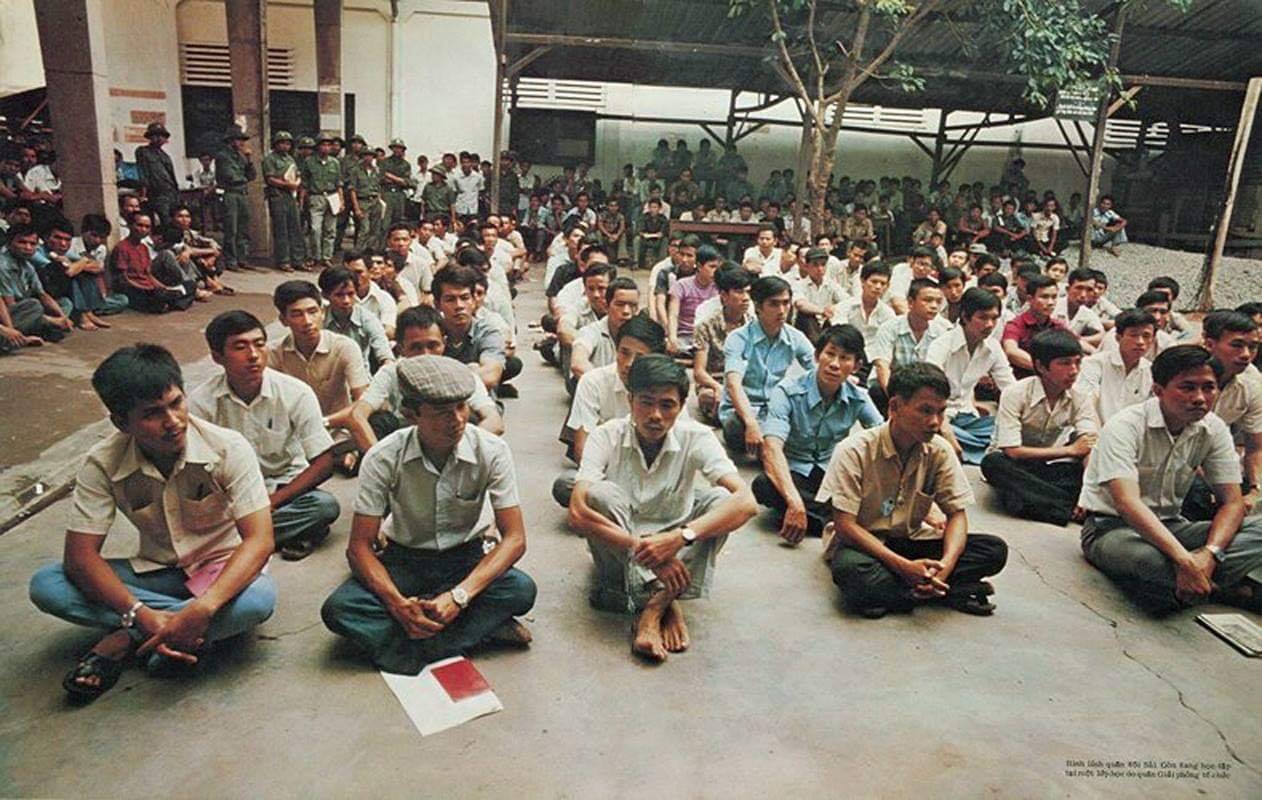

The Fall of Saigon 1975: A South Vietnamese Military Physician Remembers

"There was chaos in the streets when I made my way to the hospital on the morning of April 30, 1975. In a place of order, there was now great confusion. The director and vice director of the hospital were gone, making me, the chief of medicine, the highest-ranking medical officer."