Buried in Santa Fe National Cemetery is an aviation pioneer, flight instructor, skilled mechanic, Postal Service airmail pilot, World War I Red Cross worker, and accomplished architect. While a national celebrity and household name in the 1910s and 1920s, this trailblazer’s only legacy is inscribed on the back of husband Lieutenant Colonel Miguel Antonio Otero Jr.’s headstone, simply – “his wife.”

William Pickens, “The World’s Most Intrepid Airman is a Woman: Remembering Katherine Stinson” November 26, 19271

Katherine Stinson was born February 14, 1891, in Alabama, the first of four children. When her parents amicably separated, the children were raised by their entrepreneurial and progressive single mother. Katherine excelled in music during high school in Mississippi and desired to train as a concert pianist in Europe. The burgeoning world of aviation opened by the Wright brothers’ historic 1903 flight presented a means to achieve this goal. She went to Chicago in late 1912 and became popular aviator Max Lillie’s first female student. Within two months she earned the nation’s 148th pilot’s license, the fourth female to do so.2

Stinson quickly monetized her new skill. She and her mother incorporated the Stinson Aviation Company to make and sell aircraft. She joined the premier “Flying Circus” and performed across North America as a stunt pilot. “The Flying Schoolgirl” became the feature attraction, and she was the first woman to loop-the-loop and skywrite at night.

Other entertainment feats included racing the Indianapolis 500 winner in her plane and dropping suffragist literature on crowds in simulated bombing runs. She also achieved major aviation accomplishments in distance and endurance flying, making non-stop trips from San Diego to San Francisco and then from Chicago to New York. Throughout 1917, she toured as a distinguished guest in Japan and China, the first woman to fly in those countries. By the start of World War I, her reputation had grown to the point that she earned thousands of dollars for one afternoon of flying.3

A meteoric rise did not diminish Stinson’s pragmatism and modesty. She viewed herself as an “ordinary girl, no more courageous, clever or self-reliant than the average American woman.”4 Flying was a field open to women and a means to make money—it was work. Furthermore, she felt this work was more suited to women because of their “patience, attention to detail and caution, and intuition.”5

She designed and built her own planes and motors, maintained them, and did not leave things up to luck.6 As a result, she suffered none of the serious accidents that killed many of her counterparts. She was economically independent and made aviation a family business, training her siblings to become accomplished pilots. By 1915, Katherine’s earnings financed the Stinson Flying School and Stinson Airport in San Antonio, Texas.

Patriotism outweighed her desire to perform, however. When the U.S. Army launched the Punitive Expedition against Pancho Villa in 1916, Stinson volunteered as a pilot. She “was turned down, but had the satisfaction of knowing that most of the pilots who did go were men she had taught to fly at her school” near the border.7

When America entered World War I she again, unsuccessfully, attempted to fly for her country. She used her celebrity to contribute to the war effort at home and circumvent a wartime restriction on civilian flying. She briefly flew as the only female for the U.S. Air Mail Service and made publicity flights to raise money for the American Red Cross. The most notable was a trip from Buffalo, NY, to Washington, DC, with stops in between, where she delivered a $2 million check to Treasury Secretary William McAdoo.8

Stinson viewed World War I as the moment that would “usher in the era of the airplane.”9 Turned down for military service, she unsuccessfully offered her piloting skills to the Red Cross overseas, to “establish an aerial ambulance corps” to transport wounded troops from the front line to hospitals without the need for jostling ambulances.10 This prescient vision would not be achieved until late World War II. Stinson, instead, was accepted into the Red Cross Ambulance service and traveled overseas in October 1918. The war ended less than a month later.11

On December 20, 1918, she flew a publicity flight over London and then across the English Channel to Paris to begin in the “employ of the Red Cross.”12 Stinson still sought to fly in post-war Europe to support the troops. She tried to apply her airmail experience to deliver mail to occupation forces in Germany, and she had plans to fly over Germany in search of unreported prisoner-of-war camps.13 At least one family in Canada went through the U.S. Consulate to see if Stinson could attempt to fly into Germany and locate their missing son.14

She also began formulating a plan to set another aviation record when it was her time to return home by flying solo across the Atlantic.15

A bout of influenza was at least partially responsible for the disruption of her plans. Stinson remained largely grounded in France and worked as a chauffeur in a “docile Ford.”16 Her all-female motor corps unit was disbanded in February 1919, and she was transferred to a service totally alien and intimidating to her—canteen work. Her final month abroad was spent at rest camps, serving refreshments to doughboys and playing a piano.

On Christmas Eve 1918, her music entertained those soldiers convalescing at the Gare du Nord rest station in Paris.17 Stinson also visited the American battlefields at Chateau-Thierry and Belleau Wood. The devastation seen there and her experience with combat Veterans helped put personal wartime disappointments in perspective. She sailed home on board S.S. Harrisburg in March 1919, feeling that “any service no matter how menial was worthy.”18

Her post-war influenza, the disease that had killed millions around the globe in 1918-1919, permanently impacted her adventurous lifestyle. She entered the Sunmount Sanitarium in Santa Fe to recuperate from tuberculosis and spent years there.19 While convalescing, she came to terms with a new life, each day looking out her window at a mountain peak and realizing that her insatiable desire to climb it was now impractical and diminished, as was the thought of continuing her demanding flying career.

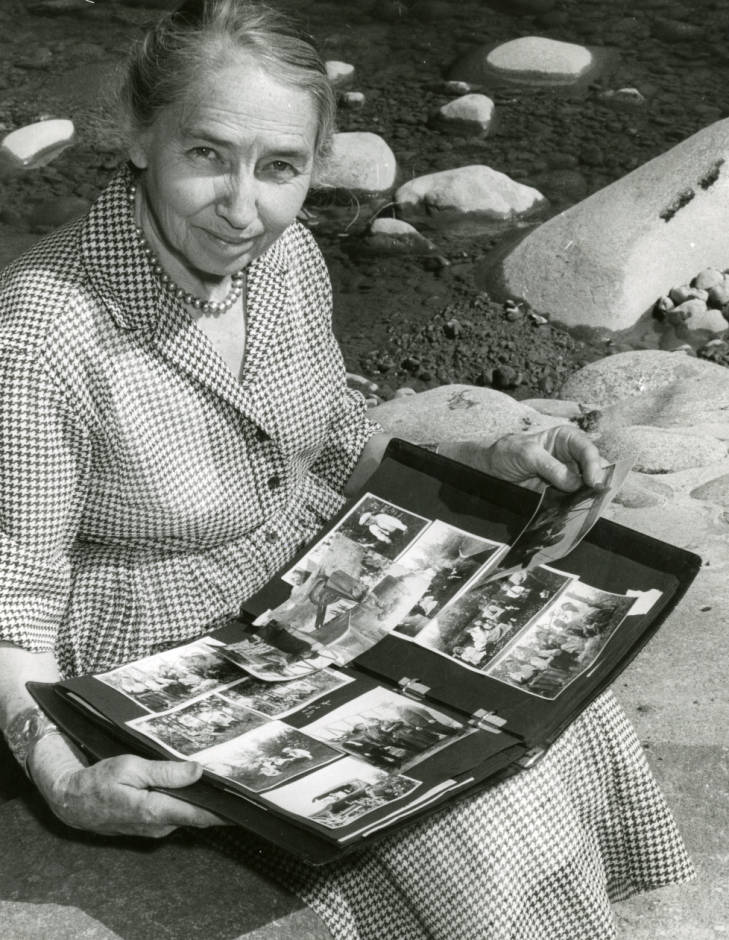

In November 1927, she married Miguel Antonio Otero Jr., the New Mexico state auditor and son of the former territorial governor, whom she met overseas when he was a young lieutenant with the American Flying Corps. She never flew again. Her national celebrity was eclipsed by the likes of Amelia Earhart, but she graciously supported all female pilots who followed in her path. For her next chapter, she was a loving spouse who applied attention to detail into a new career as an untrained architect and gained renown for Pueblo Revival Style residences she designed in Santa Fe.

Katherine developed a serious illness in 1961 that left her disabled and unable to recognize family. She suffered a stroke the following year and remained in a coma for 15 years until her death on July 8, 1977. During her burial at Santa Fe National Cemetery, a 1928 airplane made by her family business flew low over the cemetery.20 Stinson’s husband died two months later; they were married for 50 years and both are interred in Section 3, Site 1862.

While not technically a military Veteran, Stinson’s patriotic service during wartime was important. She is an example to the obstacles that women have faced in their desire to serve their country and she should be remembered for the trailblazer that she was.

Footnotes

- William Pickens, “Accelerating Sentiment,” Saturday Evening Post, November 26, 1927, 134. ↩︎

- “Birdgirl Will Navigate The Sky Over the State Fair,” The Butte Miner, September 13, 1913. ↩︎

- William Pickens, “Accelerating Sentiment,” Saturday Evening Post, November 26, 1927, 134. ↩︎

- Katherine Stinson, “Why Women Make the Best Fliers,” Sacramento Star, January 5, 1918. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- William Pickens, “Accelerating Sentiment,” Saturday Evening Post, November 26, 1927, 134. ↩︎

- “Katherine Stinson, Best of Women Pilots, Will Never Fly Again,” Victoria Daily Times, August 4, 1928. ↩︎

- William Pickens, “Accelerating Sentiment,” Saturday Evening Post, November 26, 1927, 134. ↩︎

- Katherine Stinson, “Woman’s Future in the Sky Age,” Sacramento Star, January 8, 1918. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “Miss Stinson in Ambulance Corps is Sailing Soon,” Jackson Daily News, October 18, 1918. ↩︎

- “Girl Plans Cross Sea Air Flight,” Los Angeles Record, December 21, 1918. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “Woman Aviator Seeks Mail Job,” The Blackwell Weekly (originally in Stars and Stripes), February 6, 1919, and “Miss Stinson Asked to Look for Sayre” Calgary Herald, January 3, 1919. ↩︎

- “Girl Plans Cross Sea Air Flight,” Los Angeles Record, December 21, 1918. ↩︎

- “Woman Aviator Seeks Mail Job,” The Blackwell Weekly (originally in Stars and Stripes), February 6, 1919. ↩︎

- “American Aviatrix Found a New Thrill in Feeding Doughboys Cholate Cake,” The Tulsa Democrat, June 29, 1919. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “Katherine Stinson, Best of Women Pilots, Will Never Fly Again,” Victoria Daily Times, August 4, 1928. ↩︎

- “Pueblo Revival Style was Near to Aviatrix’s Heart,” The New Mexican, March 4, 2002. ↩︎

By Richard Hulver, Ph.D.

Historian, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

A Brief History of the Board of Veterans’ Appeals

On July 28, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6230 creating the Board of Veterans’ Appeals (BVA). The BVA was created as part of the Veterans Administration (VA), which had been established only three years earlier.

Featured Stories

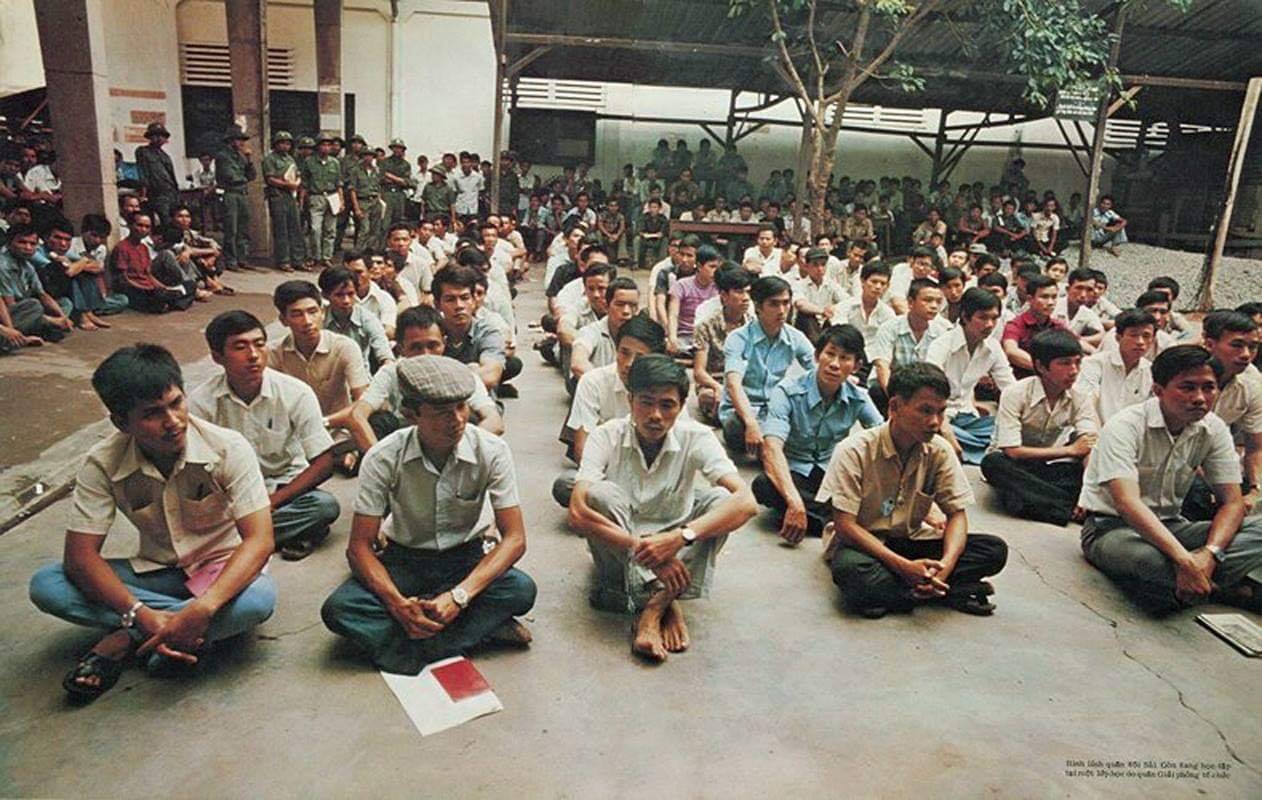

The Fall of Saigon 1975: A South Vietnamese Military Physician Remembers

"There was chaos in the streets when I made my way to the hospital on the morning of April 30, 1975. In a place of order, there was now great confusion. The director and vice director of the hospital were gone, making me, the chief of medicine, the highest-ranking medical officer."