When Vernice Ferguson became the first African American to lead the Veterans Administration (VA) Nursing Service in 1980, she inherited the largest nursing service in the nation, overseeing 60,000 professionals. By comparison, only sixty years earlier, the first African American nurses were hired to care for Black Veteran patients at the Veterans Hospital in Tuskegee. Her long and influential career as a teacher, innovator, leader, and advocate for racial parity at VA is a remarkable legacy.

With the end of World War I and a growing number of African American Veterans, in 1923 Veterans Bureau Director General Frank T. Hines instituted the first African American hospital in Tuskegee, Alabama, staffed by the first African American hospital director and all-Black staff. Under the leadership of Chief Nurse Esther Bullock, and after completing training in Greenville, South Carolina, Amelia Gears, Tresa Charles, Inithia Williamson, and Ruth Garrett became the first “complete corps” of African American nurses at a VA hospital. Their appointment was not without controversy though, as the Ku Klux Klan threatened medical staff and staged multiple demonstrations outside the hospital. After an incident in July 1923, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) requested that President Warren G. Harding send federal troops to address the situation, which was ultimately denied. Despite these challenging conditions, the nursing staff continued to care for African American Veterans at Tuskegee and the program grew in size and scope.

By 1945, a total of 109 Black nurses were caring for Black Veterans around the system of VA hospitals including at Fort Bayard, New Mexico; Kechogran, Virginia; Oteen, North Carolina; in addition to Tuskegee. That year also saw major developments for African American nurses with their professional designation status within VA, resulting in higher pay and equal status with counterparts in the Armed Services. In 1946, the American Nursing Association (ANA) accepted for membership VA African American nurses who had been barred by state organizations.

South Carolina-born Vernice Ferguson began her career in 1953, the same year that desegregation began throughout all VA hospitals. Ferguson had graduated in 1950 from New York University’s Bellevue Medical Center with a nursing degree. Despite having received an award for high scholastic standing, the school’s director of nursing refused to shake her hand.

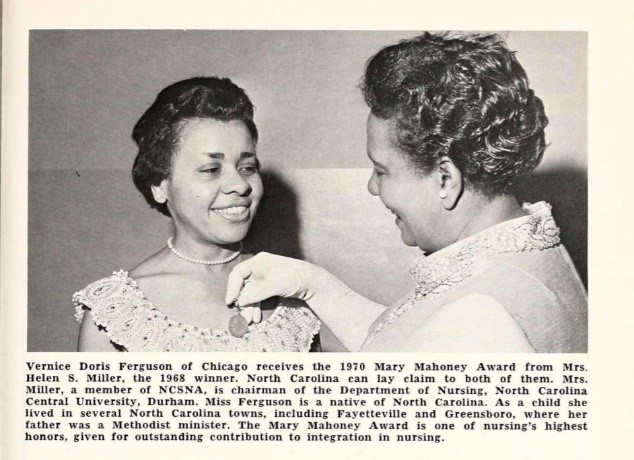

Training as one of only thirteen Black nurses at the Hines VA Hospital in Illinois, Ferguson quickly discovered that despite the strides and advancements made by African American nurses, their progress did not equate equality with White counterparts. Reflecting on her earliest days at VA, she recalled, “There were thirteen nurses of color at Hines, and they lived in containment huts on the other side of campus, while the White nurses lived in beautiful two-story Georgian buildings.” After completion of her training, Ferguson engaged in the battle to furnish Hines nurses with equal housing. It was one of many campaigns she undertook to challenge racism, for which she received the Mary Mahoney Award at the 1970 ANA Convention for “outstanding contribution to integration in nursing.”

After an eight-year stint as chief of the nursing department at the Clinical Center at the National Institutes of Health, Ferguson returned to VA in 1980 as executive for Nursing Programs. Ferguson viewed herself as a “change agent” and aimed to bring innovation and excitement to the nursing profession. Her focus on education, communication, and collaboration transformed VA Nursing from a siloed, hierarchical organization to one defined by interdisciplinary cooperation that sought to improve practices and standards while championing nurses’ voices.

Ferguson viewed education as paramount but observed, “[F]or many of my generation, and as a minority nurse, significant role models and mentors were non-existent.” Instead, she gained much of her knowledge through reading and reflection. She shared her knowledge with other nurses through a prolific publishing record, including journal articles and columns, books, and workbooks addressing ethical and diversity issues. Throughout her VA tenure, Ferguson also taught at multiple institutions, including the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the University of Illinois, Georgetown University, and the University of Maryland. Ferguson also established a VA scholarship program to provide educational opportunities for nurses – something previously available only to doctors. The VA Health Professional Scholarship Program was a key factor in the successful recruitment and retention of qualified nurses. In fact, by Ferguson’s 1992 retirement, nurse salaries had risen and the number of VA registered nurses with bachelor’s degrees or higher had more than doubled.

In addition to supporting nurses’ professional and educational development, Ferguson was deeply passionate about ensuring the mental and emotional health of nurses responsible for caring for Veterans. In 1985, she took a sabbatical from VA to join the School of Nursing at The Catholic University of America to improve her knowledge of caring for older Veterans. She did it to set an example for other nurses and show, as a leader, that nurses could and should have access to the same learning opportunities as doctors. During the sabbatical, she wrote an article revealing feelings of “depression, fright, and hopelessness” in which she proposed mental health coping strategies for nurses. Ferguson also publicly discussed her personal logistical and emotional challenges with accessing care for an aging mother. She advocated for “taking care of caregivers” and improving the lines of communication between nurses and leadership to ensure that nurses’ emotional, as well as educational, needs were met.

After retiring from VA, Ferguson continued to publish and was bestowed with many honors, including the ANA’s “Living Legends” award. She was the first nurse to win the FREDDIE Lifetime Achievement award in 2008, an equivalent to the Academy Awards for the health and medical professions. Ferguson died on December 8, 2012, at age 84, leaving behind a personal and professional legacy of equal access to services and care for nurses, Veterans, and their caretakers and families.

Sources

- “Colored Nurses in the South,” Democrat Chronicle, January 30, 1897

- “Hines Plan for Tuskegee Accepted,” Battle Creek Inquirer, August 8, 1923

- “U.S. Troops asked after Klan March,” Philadelphia Inquirer July 6, 1923

- “Nurses at VA Hospitals to get Professional Status,” New York Age, July 7, 1945

- Tar Heel Nurse Vol. 32, No. 1, March 1970

- “IT’S OK,” Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 1989

- “Honoring the Past, Treasuring the Present, and Anticipating the Future of Nursing and Health Care for Black Americans,” ABNF Journal, 1999

- “Former Top VA Nurse Shares Career Lessons,” Vanguard, May 2001

- Best Practices in Nursing Education: Stories of Exemplary Teachers, 2006

- Conversations with Leaders: Frank Talk From Nurses (and Others) on the Frontlines of Leadership, 2007

- “For the First Time, Nurse Wins Lifetime Achievement Honor,” Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 2009

- “Vernice D. Ferguson, NYU Nursing Alum, Head of the Veterans Affairs and National Institutes of Health Nursing Departments, Dies at the Age of 84,” New York University, December 10, 2012

- “Vernice D. Ferguson, Leader and Advocate of Nurses, Dies at 84,” New York Times, December 22, 2012

By Janice Young, VA Central Office Library; Kirsten Cessna, MLIS Student Volunteer; and Katie Rories, Historian, Veterans Health Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

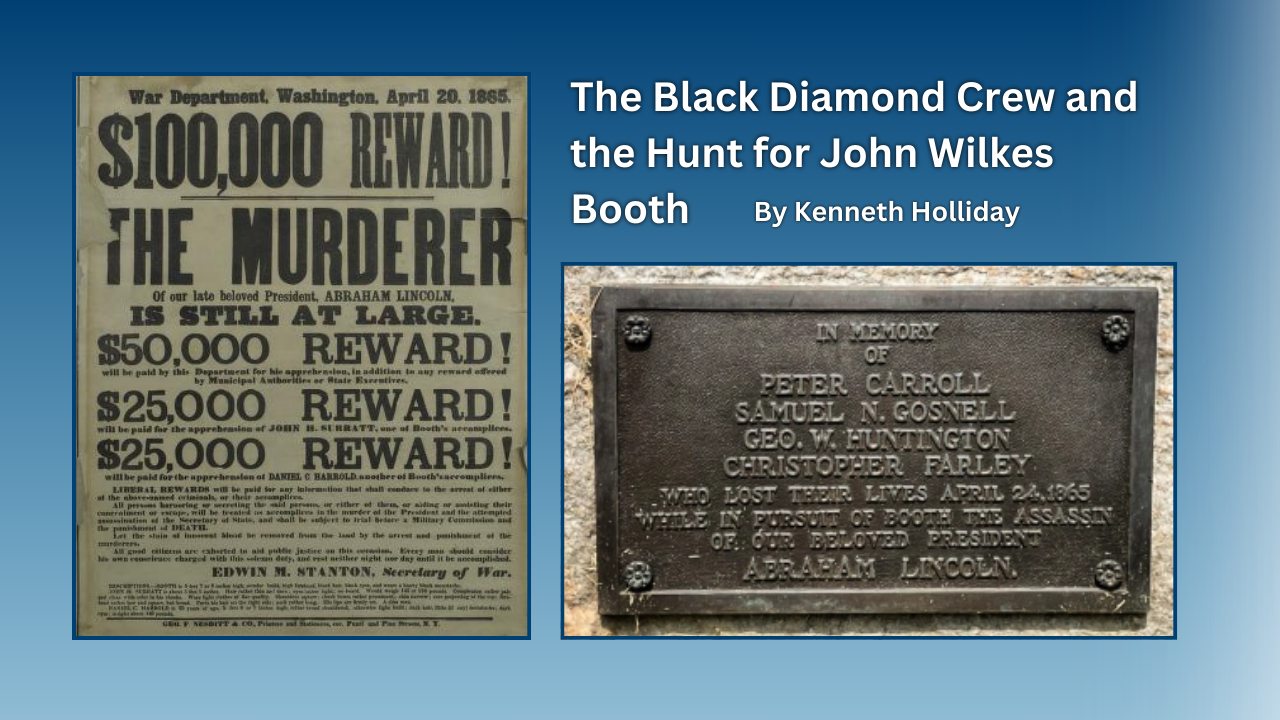

During the late evening, early hours of April 23-24, 1865, the Black Diamond, a ship on the Potomac River searching for President Abraham Lincoln's assassin John Wilkes Booth collided with another ship, the USS Massachusetts. The incident was a terrible accident during the frantic mission to locate the fleeing Booth before he escaped into Virginia. Unfortunately many lives were lost, including four civilians who had been summoned from a local fire department by the Army. For their assistance during this military operation, all four were buried in the Alexandria National Cemetery, some of the few civilians to receive that honor.

Featured Stories

In the mid-twentieth century, the lives of Dr. Ivy Brooks and Mildred Dixon, two trailblazing Black women physicians, converged at the Tuskegee, Alabama, VA Medical Center. Doctor's Ivy Roach Brooks and Mildred Kelly Dixon shared much in common. Both women were born in 1916 in the northeastern United States and received training in East Orange, New Jersey. They both launched careers in alternate medical professions before entering the fields of radiology and podiatry, respectively. Pioneering many “firsts” throughout their professional lives, both women faced and overcame the rampant racism and sexism of the era.

Featured Stories

After the United States entered World War I in 1917, American Expeditionary Force commander General John J. Pershing requested the recruitment of women telephone operators that were bi-lingual in English and French. Eventually 233 were selected out of over 10,000 applicants, and they served honorably through the war, earning the nickname of 'Hello Girls.'

However, their employment was not officially recognized as military service and therefore were neither honorably discharged, or eligible for the benefits other returning Veterans would receive. This kicked off a 60-year fight for 'Hello Girls' to receive legal Veteran status.