Founded in 1866 as a fraternal organization for Union Veterans, the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) embraced a new mission in the 1880s: political activism. The GAR formed a pension committee in 1881 for the express purpose of lobbying Congress for more generous pension benefits. Legislation to that date limited Civil War pensions to Union Veterans with injuries or ailments that were a direct result of their military service. The GAR wanted to expand coverage to include all deserving Union Veterans who had served their country honorably.

The GAR’s aggressive advocacy on the pension issue revived the organization’s flagging popularity. Its membership skyrocketed from 26,000 in 1876 to over 400,000 by 1890. Its tremendous growth transformed the order into a powerful force in national politics and ensured that the GAR’s proposals received a careful hearing in Congress by members of both parties.

Republican politicians were quick to embrace the organization’s push for more expansive benefits. They often framed their support on moral grounds, maintaining that the nation had an obligation to provide for the men who had fought to preserve the Union. Democratic leaders were sympathetic to the Veterans’ cause and recognized their sacrifices. But Democrats also worried that any expansion of the pension system would jeopardize their ability to cut spending and lower taxes.

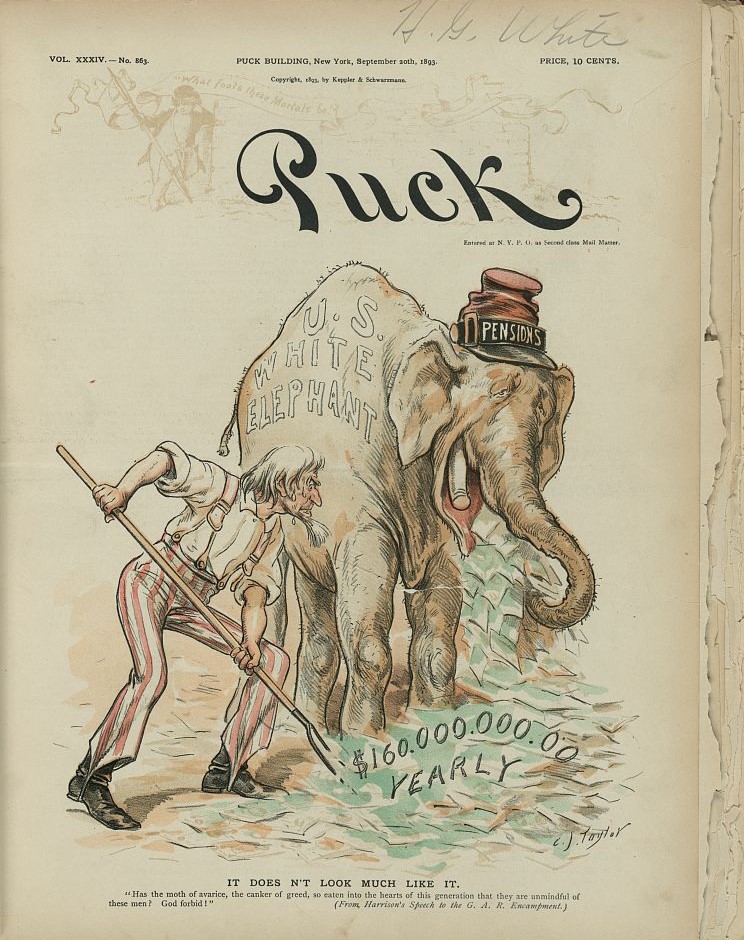

The GAR rewarded the Republicans’ pro-pension stance by helping the party capture both Congress and the presidency in 1888. Republican legislators repaid the favor in 1890 by passing a pension bill that awarded a monthly payment of $6 to $12 to all Union Veterans who served for at least 90 days, received an honorable discharge, and were deemed incapable of performing manual labor due to any kind of disability, regardless of cause. The GAR pension committee called it “the most liberal pension measure ever passed by any legislative body in the world.” About 400,000 Veterans claimed a pension under the law within three years. During this same stretch, government spending on the pension system jumped from $109 million to $161 million.

The Grand Army scored a second major legislative victory in 1907 with the passage of another liberal pension bill. Under this statute, eligibility for a pension and its cash value became age dependent. Veterans automatically qualified for a $12 pension at age 62, increasing to $15 at age 70 and $20 at 75.

After the 1907 pension act went into effect, GAR leaders appeared satisfied with their accomplishments. At the GAR’s 1908 national encampment, the pension committee declared: “may we not now consider the work of general pension legislation for at least a few years closed.” But not all Veterans agreed. From 1907 to 1911, GAR unity splintered over proposals to raise service pension rates to $30 a month or $1 a day. Many GAR members supported the increase. Others believed it was asking for too much.

Congress was also divided. In a sign that the political landscape was shifting, however, the battle over dollar-a-day pensions was not waged on strictly partisan grounds. In the House, Ohio Democrat Isaac R. Sherwood introduced one of the first dollar-a-day pension bills in late 1907. General Sherwood as he was called, in recognition of his Civil War rank, championed the legislation in multiple major speeches on the floor, urging its passage as “a measure of patriotic justice.”

An artifact from the political wrangling over pensions is now part of the permanent collection of the National VA History Center in Dayton, Ohio. The item is a small ribbon displaying the message: “I endorse the $1 per day pension as recommended by the Departments of Ohio and Indiana G.A.R.” The button attached to the ribbon features two American flags and the phrase “saved by the boys of ’61-65.” The back of the ribbon bears the signature of Horatio C. Claypool, a Democratic judge who ran for the seat in Ohio’s eleventh Congressional district in the 1910 mid-term elections.

On the campaign trail, Claypool presented himself as a friend of the Veteran and he backed the Sherwood bill. Sherwood, in turn, sought to bolster Claypool’s electoral prospects by blanketing the judge’s district with circulars accusing the Republican incumbent of opposing Veteran-friendly legislation. Sherwood’s supporters credited him with delivering the “old soldier vote” to Claypool.

Claypool won the seat as part of a broad Democratic victory that handed the party control of the House for the first time since 1895. In 1912, Congress ended the impasse over the dollar-a-day pensions by approving a new benefits bill on a bipartisan vote. The bill is often called the Sherwood Act, although it did not deliver on everything the Ohio lawmaker wanted. The compromise measure determined pension payments on a sliding scale based on age and length of service. The dollar-a-day rate was reserved for two classes of Civil War Veterans: men 75 years or older who had served for at least two years and individuals with service-connected disabilities that left them unfit for manual labor. The law also granted the same amount to any surviving Veteran of the 1846-48 Mexican War.

The Sherwood Act was the last major piece of Civil War pension legislation before World War I. The issue itself lost its political salience as the GAR declined in size and influence with the passing of the Civil War generation. After the United States entered the Great War in 1917, Republicans and Democrats were far more concerned with creating an equitable benefits system for the new cohort of Veterans.

By Gage Huey, Museum Collections Manager, National VA History Center, and Jeffrey Seiken, Ph.D., Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.