“The following pages are devoted to the memory of those heroes who have given up their lives upon the altar of their country, in defense of the American Union.”

So opened the preface to the first volume of the Roll of Honor, a compendium of over 300,000 Federal soldiers who died during the Civil War and were interred in national and other cemeteries. The genesis of this 27-volume collection published between 1865 and 1871 can be traced to Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs and the department he oversaw for a remarkable 21 years from 1861 to 1882.

The need for such an inventory was pressing even before the guns fell silent. During the Civil War, interment of the fallen was left to officers whose primary concern was defeating the enemy and preparing for the next march or battle. In many instances, conditions on the field did not lend themselves to careful burial. As soon as the conflict ended, Meigs and the Quartermaster Department turned their attention to giving a full accounting of the dead.

To assist with this process, every Union regiment was required to submit a final roll that included the names of all unit members who were killed, mortally wounded, or died of disease. Shortly afterwards, in July 1865, Meigs ordered that “officers of the Quartermaster’s Department who have made interments on battlefields during the war, will report the number of the same, giving the localities, dates of battles, and dates of interment.” These reports became the basis for the Roll of Honor.

Concurrent with the effort to catalog the wartime dead was a vast reburial movement. The 101,736 registered burials listed in wartime records represented less than a third of the estimated number of Union dead. As historian Drew Faust noted, “It was clear that hundreds of thousands of northern soldiers lay in undocumented locations . . . their deaths unknown to their families as well as to military record keeping.”

The man initially tasked with tabulating the lists was Capt. James M. Moore, the Army’s Assistant Quartermaster General. The Government Printing Office produced the first volume of Roll of Honor in 1865. The cover featured several lines from the celebrated 1847 poem “Bivouac of the Dead,” which had been written to memorialize the dead from the Mexican War of 1846-48. Meigs contributed the introduction, explaining that this list of “victims of the rebellion” was being published “for the information of their comrades and friends.”

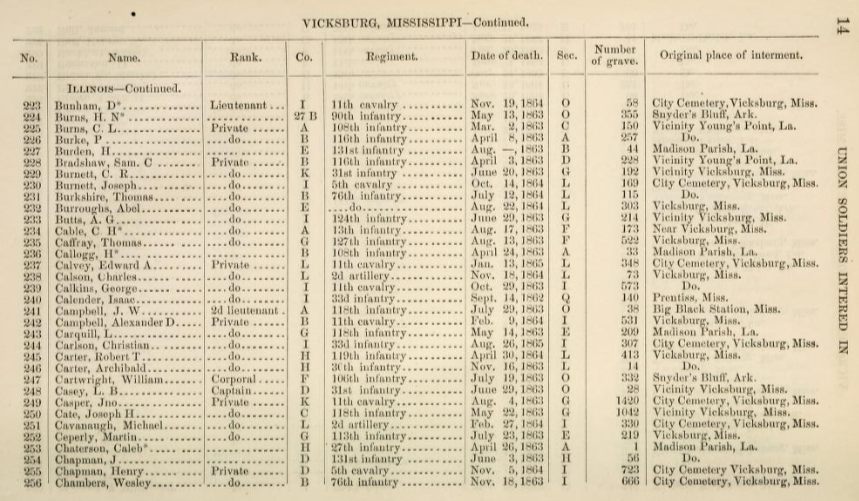

The volume detailed the gravesites of soldiers interred in Washington, D.C., Arlington, Virginia, and those killed in the opening battles of the 1864 Virginia Overland Campaign. The names of the fallen were listed in alphabetical order within each cemetery along with their grave number, rank, regiment and company, and date of death. The rest of the series followed the same format, although later volumes included a column specifying each soldier’s original place of interment.

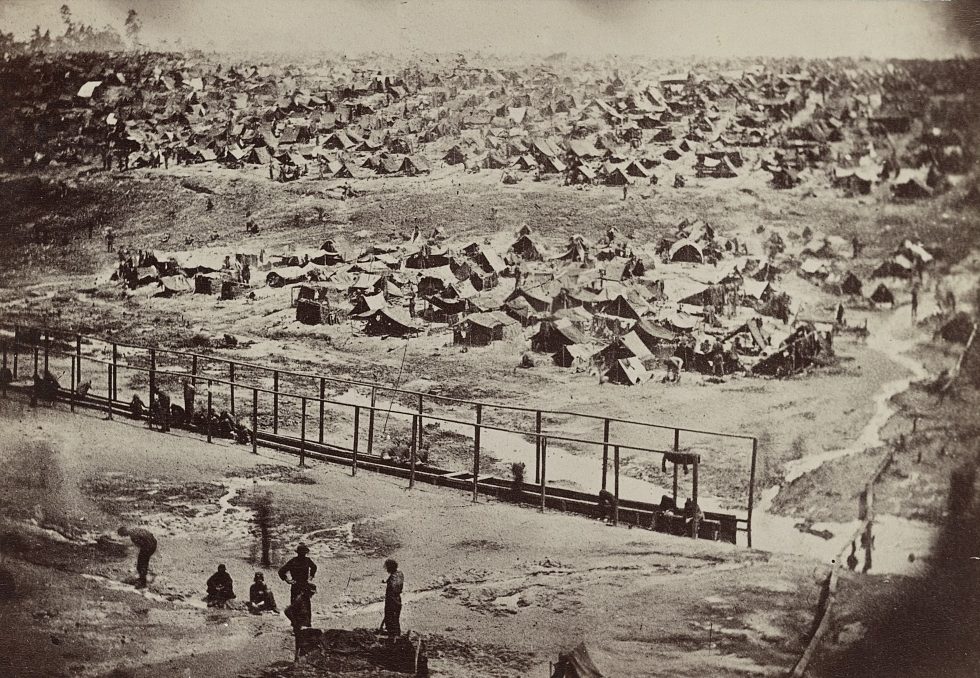

Every volume was a painful reminder of the human costs of the war, but the third volume released in 1866 carried extra emotional weight. It was published under the title The Martyrs Who, For Our Country, Gave Up Their Lives in the Prison Pens in Andersonville, Ga.

The report contained the names and personal information of the more than 12,000 Union soldiers who perished at the notorious Confederate prisoner of war camp. The dead had originally been buried in shallow trenches. In July 1865, Captain Moore led two companies of soldiers to Andersonville. Over the next three weeks, through meticulous detective work using prison hospital records, they succeeded in identifying all but 451 of the bodies. His team reinterred the remains in the national cemetery they established at the site.

The Quartermaster Department eventually determined that 316,233 Union soldiers had been buried during the conflict and it identified about 55 percent of them. In 1868, Col. Charles W. Folsom was appointed Inspector of National Cemeteries. Soon after, he wrote to a prominent newspaper of his team’s efforts to establish the identity of the Union war dead:

Every pains [sic] was taken to preserve all memorials of identity, from the scrap of a letter hastily pinned on the breast or buried in a can or bottle with the remains, up to the rudely-ornamented headboard which comrades provided were more time was allowed.

Yet, while Moore, Folsom, and the others in the Quartermaster’s Office did their best to ensure the veracity of the information published in the Roll of Honor, errors and omissions were unavoidable. Colonel Folsom acknowledged the inaccuracies in the volumes and he thought a consolidated report listing the dead alphabetically by state would help resolve the mistakes.

The War Department never produced such a report. More than a century later, however, in 1995, a private publishing company printed an Index to The Roll of Honor. This book compiled all of the names of the deceased from the Roll of Honor into a single alphabetical list, complete with the page number and volume where each name could be found. Although the publisher made no attempt to correct the mistakes and duplications from the original, the index still serves as a valuable guide to the contents of the 27 volumes.

Even with its flaws, the Roll of Honor remains after 160 years one of the principal sources consulted by historians and genealogists conducting research on Union soldiers interred in our national cemeteries. The series also attests to the nation’s commitment after the Civil War to honoring the Union dead and documenting their final resting place for the benefit of the families, friends, and comrades they left behind.

By Jimmy Price

Historian, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.