Unlike previous wars, the federal government in the Civil War arranged to care for returning soldiers too weakened by their wounds, the lingering effects of disease, or the hardships of military life to care for themselves. In the decades after the war, the government established a network of eleven residential facilities known collectively as the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. First reserved for Union Veterans, the National Homes eventually admitted former soldiers and sailors of any conflict save for those who fought for the Confederacy.

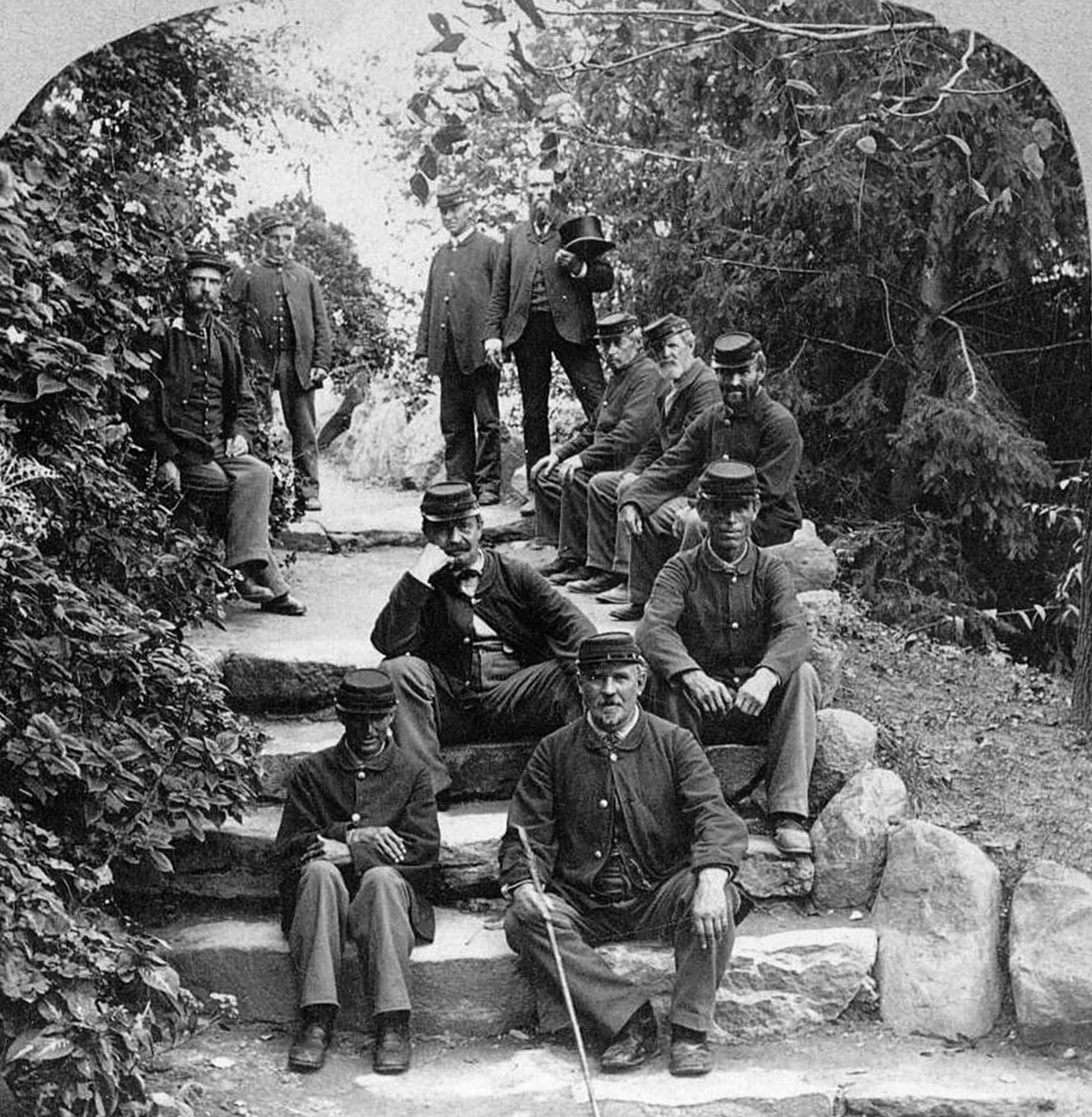

National Home branches were organized along military lines. Residents lived in barracks, ate in mess halls, wore uniforms, and followed Army regulations. At the same time, the Board of Managers for the National Home sought to invest the sites with many of the trappings of home and community, adding such amenities as chapels, libraries, theaters, and playing fields.

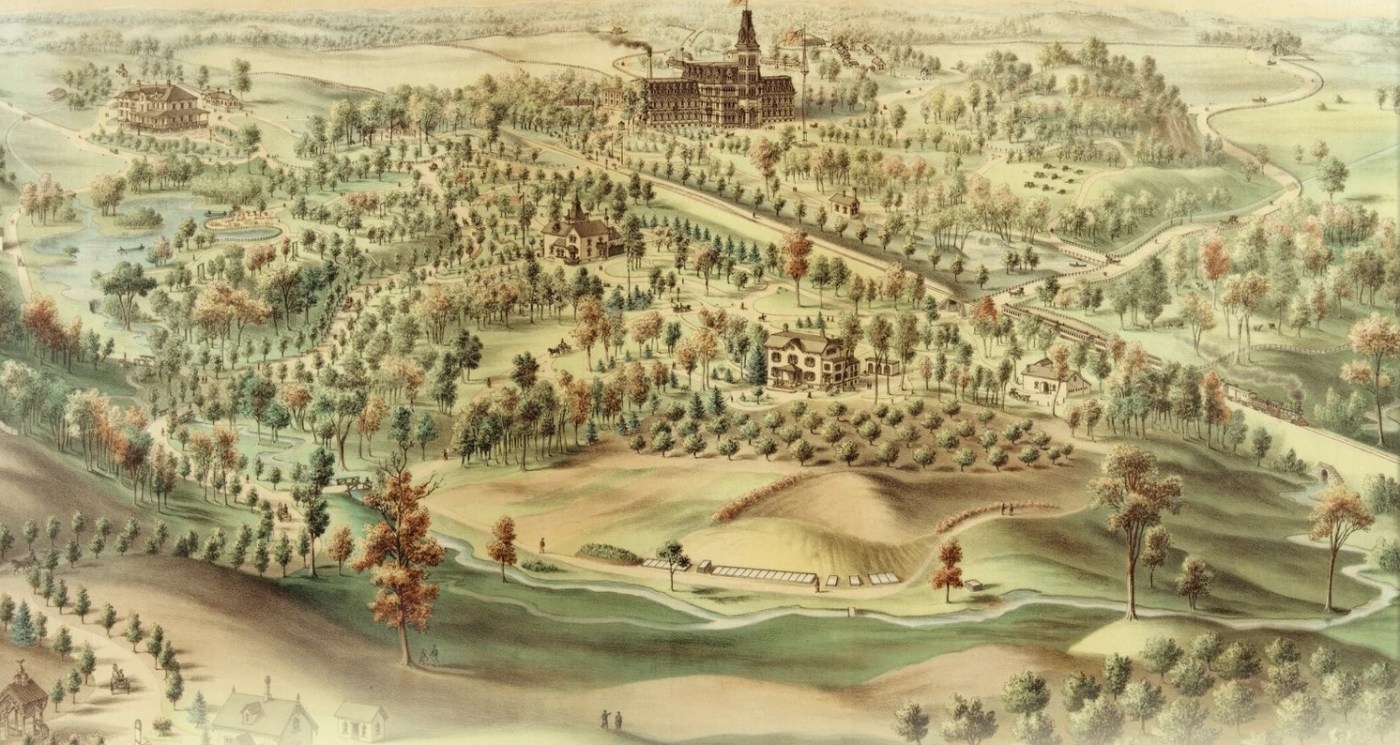

Great care also went into the shaping of the physical environment. The board employed landscape architects to design the grounds of each branch to create an attractive, idyllic setting for residents and visitors alike. Influenced by the picturesque landscape movement, they adorned the National Home campuses with man-made ponds and lakes, ornate flower gardens, elaborate plantings of shrubs and trees, winding trails, and other features to beautify the properties.

The Central Branch in Dayton, Ohio, exemplifies the landscape architecture at the National Homes. It opened in 1867, joining the Northwestern Branch in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and the Eastern Branch in Togus, Maine, as the first three sites in the National Home system. The Board of Managers located the branch on several hundred acres of farmland three miles west of Dayton’s downtown. Thomas B. Van Horne, an experienced landscape architect who served as a chaplain in the Union Army during the Civil War, created the layout for the grounds here as well as at the Milwaukee Home.

The Dayton campus had a military bearing, with barracks arranged in orderly rows adjoining the western side of the central parade ground. But Van Horne turned the eastern part of the property into a scenic park. Walking paths encircled the four artificial, spring-fed lakes that were formed by widening and deepening the pits left by the limestone quarried for building material. Groves of trees, decorative gardens, patterned flower beds, and a rock grotto with waterfall and drinking springs also graced this side of the campus.

One of the earliest residents, Frank Mundt, was a florist and gardener by trade and he scoured the surrounding countryside for wildflowers and vines, which he then transplanted to the grotto area to luxuriant effect. Residents also cultivated many species of exotics plants and flowers in the Home’s two conservatories for display on the property.

Over time, the Dayton Home supplemented the splendors of the natural world with creatures from the animal kingdom, establishing a zoological garden that included an aviary for birds, a deer park, and an alligator pond. At the height of the Home’s popularity around the turn of the century, over 500,000 people turned out annually to tour the grounds and view the wildlife menagerie and other sights.

While not quite as big of a draw as Dayton, the other branches of the National Home also attracted thousands of visitors from the surrounding areas. Their aesthetically pleasing grounds, gardens, and waterways offered visitors a welcome refuge from city life and a public space to experience and enjoy nature. Many sightseers arrived by rail, trolley, or streetcar lines that connected the National Home sites to the nearby urban centers. Some branches also built hotels to accommodate guests who wished to stay overnight.

The popularity of the National Homes as a tourist destination strengthened the ties between the Veterans and the local citizenry and integrated the branches into the social and economic life of the neighboring communities. Of course, the pleasures of wandering the carefully manicured campuses or picnicking by one of the man-made lakes were not reserved for visitors alone. The Veterans themselves enjoyed the therapeutic benefits of living in a wholesome environment with the attractions of nature close at hand. Many of the more able-bodied men also played a direct role in the upkeep of the grounds, tending the gardens and assisting with other beautification projects.

After World War I, the National Home branches were incorporated into the expanding hospital system for Veterans overseen by the Veterans Administration. Their populations dwindled over time as the focus of these facilities shifted to in-patient medical care rather than long-term residential services. The physical appearance of the campuses also changed as old construction was replaced with new and the ornamental landscaping features that once delighted visitors deteriorated or disappeared.

The VA Medical Center in Milwaukee that now occupies the site of the Northwestern branch, for instance, retains only one of its four original lakes while the VA medical facility at the old Danville, Illinois, Home drained its lake and replaced it with a golf course. The grotto and gardens at Dayton also suffered from neglect and became badly overgrown. In recent years, however, the grotto has been renovated and a dedicated corps of volunteers has restored the floral gardens to something of their former glory.

For more on this subject, visit our digital exhibit Landscaping and Architecture at the National Home.

Note: This story was originally posted under a different headline and lead image. This was updated on Dec. 12, 2023 to its current form.

By Maureen Thompson, Ph.D., Historian, Central Alabama VA Medical Center-Tuskegee and Jeffrey Seiken, Ph.D., Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.