In 1776, the fledging American government passed the first national law compensating soldiers and sailors disabled in the Revolution, but it was slower to make any provisions for widows. Not until 1780 did the Continental Congress approve a resolution awarding widows’ pensions to women who lost a spouse in the war and this act only applied to the wives of officers.

Under the terms of the law, the widow was to receive half her husband ’s pay for seven years from the time of his death, which is the same pension the officer would have been granted after the war if he had lived and served for its entirety. In the 1790s and early 1800s, Congress periodically passed new laws providing half-pay pensions for widows of officers who died while serving but reduced the duration to five years. However, the expiration date was not absolute. Legislators as a rule renewed such pensions after the five-year period expired and finally made them a lifetime benefit before the Civil War.

Prior to the War of 1812, the federal government paid little heed to the plight of women whose deceased husbands were not commissioned officers. In the immediate aftermath of the war, Congress finally began offering pensions to the wives of all service members who died in action. This policy continued in subsequent wars. Military rank still mattered, though, as it determined the cash value of the award. Up through the Civil War, payment ranged from as little as $4 to $8 a month for the wife of a private to $30 a month for a woman married to a lieutenant colonel or higher-ranking officer.

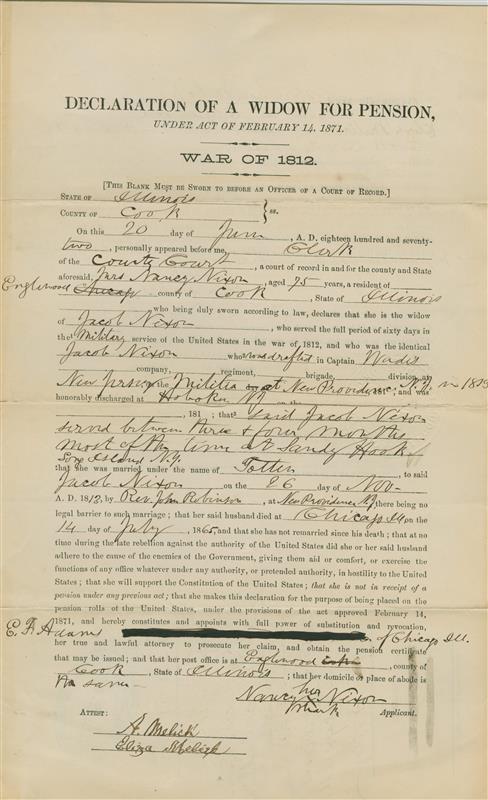

To apply for a widow’s pension, a woman had to submit a sworn declaration stating the facts of her case. She also had to furnish evidence of her legal marriage to the deceased and other documentation corroborating the details of her story. A marriage certificate was the best proof. But a claimant could present other forms of evidence such as affidavits from neighbors who knew the couple or a family keepsake inscribed with the date of the wedding. These applications could generate a lengthy paper trail, especially if the pension official handling a claim had any questions about its legitimacy.

Through the 1820s, widows’ pensions were reserved for women whose husbands died as the direct result of their military service. In 1832, however, Congress decided to grant full pay for life to all surviving Revolutionary War Veterans who had served for two or more years and a lesser amount if they had served for at least six months. In 1836, a full fifty-three years after the war ended, the government extended the same benefit to their widows.

Initially, women qualified for the pension only if they were married at the time of the war, but later amendments to the law first relaxed and then dispensed with this requirement altogether. Widows of men who fought in the War of 1812, the Mexican War, and on the Union side in the Civil War also became eligible for pensions after lengthy interludes of time, although the wives of Union Veterans got off relatively easy compared to their Revolutionary War and War of 1812 counterparts. While the latter had to wait more than 50 years before they could seek a widow’s pension, Congress began accepting claims from the former in 1890, a mere twenty-five years after the conflict ended.

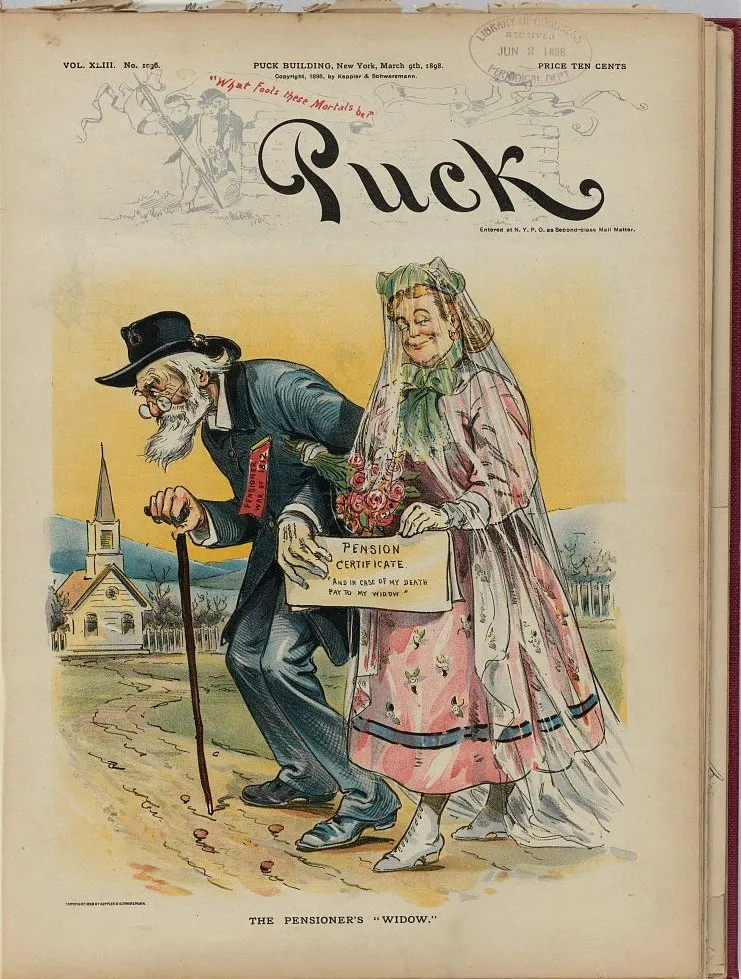

A woman forfeited her widow’s pension when she remarried, although she could seek its reinstatement if her new husband died. An unintended consequence of this rule was that some widows who found a new partner opted for cohabitation rather than marriage in order to continue collecting a pension from the government. Congress closed this loophole in 1882 by making “adulterous cohabitation” grounds for terminating a pension. Then there was the reverse situation. The dispensing of the requirement to be married at the time of military service also led to many May to December romances between elderly Veterans and women decades younger. Such marriages generated some public amusement, but they benefitted both parties. The aging Veteran gained companionship and care in his final years, while his youthful bride stood to receive a widow’s pension after his passing.

By Jeffrey Seiken, Ph.D.

Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.