The first permanent informational plaques placed in national cemeteries after the Civil War were affixed to upright cannons to brand these sites as a shrine to Union dead. Major and Brevet Colonel Oscar A. Mack, the inspector of national cemeteries, recommended the plaques in his April 1872 report. By then, the U.S. Army oversaw 72 national cemeteries and an estimated 250,000 Union graves, most marked by wooden headboards.

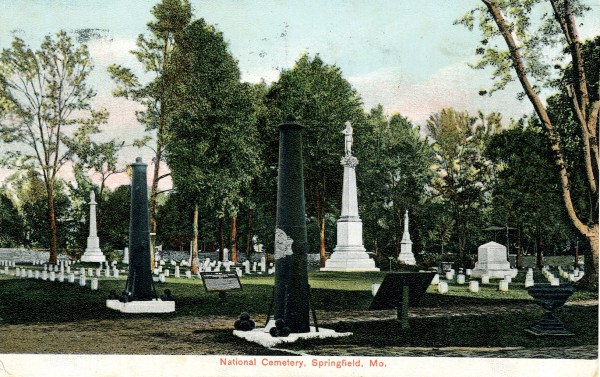

Many cemeteries already contained “large iron guns…planted vertically on their bases as monuments.” Mack observed that “a bronze shield, bearing in raised (cast) letters…might be attached to one of these guns…in such a way to improve its appearance and increase its usefulness as a monument.” Mack’s superior, Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs, agreed that “no cemetery can be considered properly furnished till some considerable monumental brass bears an inscription recording its establishment, and the number of dead soldiers it contains.”

On October 5, 1872, Secretary of War William Belknap authorized the acquisition of bronze shield plaques as far as the annual appropriation for the national cemeteries, which paid for lodge construction, headboards, superintendent’s salaries, and other expenses, would allow. The Quartermaster General’s office immediately wrote to a Philadelphia foundry, describing the shield and for each, “a drill and tap and bronze screws” to secure it to the gun.

The manufacturer of the shield is not known, but Mack’s 1874 inspection confirms it was designed to fit on the 24-pounder cannon common to most cemeteries. Springfield National Cemetery in Missouri contained six “gun-monuments.” Among these, Mack reported, were two flanking the main drive, and “one of these has the prescribed bronze shield on it.”

The plaque’s Federal-style eagle with outspread wings and shield cast with stars and stripes is representative of the Republic’s nineteenth-century seal. Beneath the eagle is the cemetery name, establishment year, and number of known and unknown interments. To either side are military symbols of the Civil War era: cannon for artillery, swords for cavalry, bugle for infantry, and flags to denote regiments.

By Sara Amy Leach

Senior Historian, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.