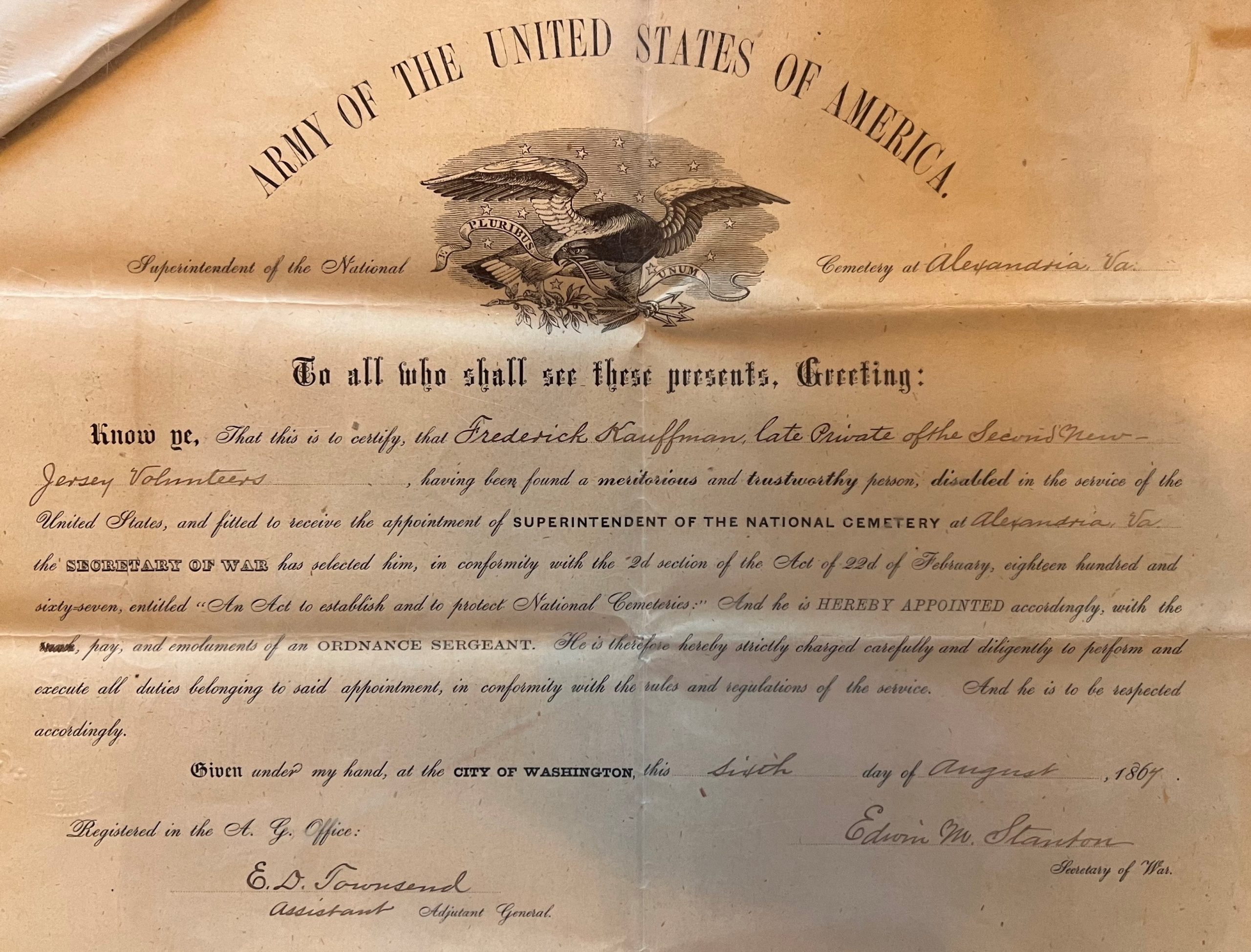

The 1867 “Act to establish and to protect National Cemeteries” directed the Secretary of War to appoint a superintendent for each cemetery who was to reside in a lodge at the main entrance of the property. The superintendent’s principal duties involved greeting visitors, answering their questions, and taking care of the grounds. The statute also contained a key condition for their employment—the superintendents’ positions were to be reserved for enlisted men with disabilities stemming from their service in the Union Army during the Civil War. Five years later, Congress broadened and refined the eligibility requirements to include “either commissioned officers or enlisted men of the volunteer or regular army, who have been honorably mustered out or discharged from the service of the United States, and who may have been disabled for active field service in the line of duty.” After the 1867 law went into effect, the Army provided superintendents with printed disability certificates affirming that the recipient had “been found a meritorious and trustworthy person, disabled in the service of the United States.” The ornate certificates were most likely intended for public display to assure visitors that the superintendent possessed the requisite qualifications for the job.

Melker M. Jefferys was one of the Union Veterans with service-related injuries who benefited from the law. A native of what became the state of West Virginia during the Civil War, he enlisted as a private in the 15th West Virginia Infantry. In sweltering heat on June 18, 1864, his regiment advanced against Confederate artillery during the battle of Lynchburg, Virginia. A shell struck Jefferys, taking his right hand and a portion of his forearm. Despite the severity of his wounds, he managed to make his way to a Union field hospital where a surgeon amputated what remained of his arm just below the elbow. His ordeal, however, was far from over. Confederate forces carried the day and drove the Union troops from the field. Jeffreys was captured and transported some 110 miles to a hospital in Richmond. He remained there convalescing until a prisoner exchange at the end of August led to his parole and transfer to a Union hospital in Grafton, West Virginia. He was formally discharged from the service in September 1865, five months after the Civil War ended.

Jefferys returned to civilian life in Preston County, West Virginia. He applied for and received a government pension of $8 a month for his wartime wounds. As this modest amount was insufficient to live off of, he attempted to return to his pre-war occupation of farming. He was outfitted with a prosthetic on his arm, but the hard manual labor proved to be too physically demanding. He left farming to become a schoolteacher and married Mary E. Baker in 1869. He continued working as a teacher for the next six years while he started a family with his new wife.

In 1875, Jefferys embarked on a new career, parlaying his military service and disability into an appointment as superintendent of Grafton National Cemetery in West Virginia. The government acquired the three-acre site under the 1867 law for the burial of Union soldiers who had died on the battlefield or in hospitals in the state of West Virginia. Over 1,200 men were interred there, half of them unknown. Jeffreys relocated his wife and children to Grafton and oversaw construction of the new stone lodge that would serve as his family’s place of residence.

Jefferys settled into his new responsibilities, overseeing funerals, keeping the cemetery records, engaging with visitors, and maintaining the landscape. He was also diligent about improving the cemetery and securing more money for its upkeep. In January 1878, he circumvented the normal chain-of-command to lobby the Army to upgrade Grafton’s “fourth-class” rating, the lowest category in a budget tier that determined the funds allocated for cemetery maintenance. Jeffreys’ actions annoyed his superiors and he had to wait another four years before the Army raised Grafton to third class and rewarded him for “faithful and meritorious” service with a pay raise.

Jefferys worked at Grafton for 20 years, save for a six-month temporary assignment to Alexandria, Virginia, in 1887. His wife, Mary, died during his time there and was buried in the cemetery. He went on to serve as the superintendent at four other national cemeteries: Cold Harbor and Fredericksburg in Virginia, and Philadelphia and Gettysburg in Pennsylvania. He earned plaudits from the Fredericksburg locals, who described him as “the most efficient superintendent of the cemetery here” and “a fine gentleman [who] has kept the cemetery in excellent condition.” Jeffreys remarried twice, losing his second wife in the process, and fathered a total of seven children.

For medical reasons, Jefferys retired from his final superintendency at Gettysburg National Cemetery on May 8, 1915, at age 69. He was afterward admitted to St. Elizabeths Hospital, a mental asylum in Washington, D.C. He stayed a patient at the hospital for his remaining years. On February 22, 1920, Jefferys succumbed to what doctors described as senile dementia. His body was returned to his home state and laid to rest in Grafton National Cemetery (Section F Site 1297) near his first wife and the many West Virginia soldiers whose graves he had tended decades earlier.

By Richard Hulver, Ph.D., Historian, National Cemetery Administration, and Jacob Klinger, Graduate Intern, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

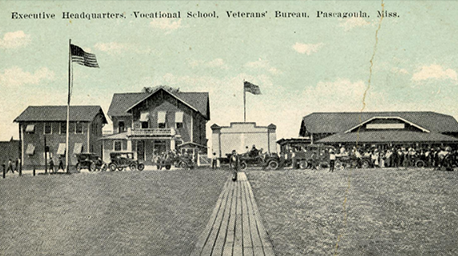

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.