From World War I through Vietnam, more than 1,000 Americans were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest decoration for valor. The wall display outside the offices of VA’s Under Secretary for Benefits in Washington, D.C., pays tribute to a select group of them: the 98 recipients who after serving their country chose to serve their fellow Veterans by going to work for VA. Their names are inscribed on metal plates affixed to the large plaque at the bottom of the display, organized by conflict and then alphabetically (with the exception of a few names at the end).

VA exhibit designer William Hester, Jr., researched and built the display sometime around 2010. The prolific Hester, who worked at VA for close to 40 years before retiring in 2015, created by his own estimate about 400 exhibits at VA facilities and other locations over the course of his career.

The service members who received the Medal of Honor for acts of bravery during World War II make up more than half of the names on the plaque. The VA tripled the size of its workforce after the war and General Omar N. Bradley, who became head of the agency in 1945, actively recruited Veterans to fill out its ranks. All-told, about one in eight Medal of Honor recipients from the World War II generation ended up finding employment at VA.

Hershel “Woody” Williams was one of these new hires. Serving as a demolition sergeant with the 3d Marine Division, Williams earned his decoration for almost singlehandedly destroying a Japanese pillbox nest during the Battle of Iwo Jima in 1945. The savage month-long campaign to secure the small island in the Pacific cost the Marines over 25,000 casualties and produced 27 Medal of Honor awardees, the most of any single operation in U.S. history.

Following his discharge from the military, Williams returned to his native state of West Virginia. He had just started working as a supply officer in an engineering firm when VA offered him a position as a contact representative in its West Virginia regional office. The starting salary was five times higher than his monthly pay in the Marine Corps, which made the decision to accept the offer an easy one. As he later recalled in an interview, however, the rewards of the job went well beyond the material.

“After I got involved and was able to, most days, do something to assist people that maybe would have never received that assistance, you’d always come home in the evening feeling good and anxious to get back to work the next morning because you knew that you were going to be able to do something that would help somebody,” he said. The satisfaction of aiding other Veterans on a near daily basis sustained him through thirty years of public service. He retired from VA in 1976.

Many of Williams’ fellow Medal of Honor recipients from the war followed him into the same line of work at VA. As contact representatives, they met with Veterans and their dependent and counseled them about the different benefit programs available to them. Most were based at VA regional offices, which served Veterans seeking benefits in designated geographic areas. During the Vietnam War, a few contact representatives had the opportunity to trade their civilian clothes for combat fatigues and spend three months in South Vietnam advising soldiers preparing to separate from the Army.

Marine Veteran Robert E. Bush, who received his Medal of Honor at the same White House ceremony as Hershel Williams, volunteered to join the first team of contact representatives participating in the program, which started in 1967. Bush earned his medal leading his squad on an assault in the face of withering enemy fire on Okinawa in 1945.

While being treated for his wounds after the attack, he threw himself on a grenade to protect the men around him, an act of self-sacrifice that cost him several fingers and the use of one eye. Bush was located at the Chicago regional office when he took the assignment to go to Vietnam. Hershel Williams, fittingly enough, led the second team of volunteers that arrived three months later.

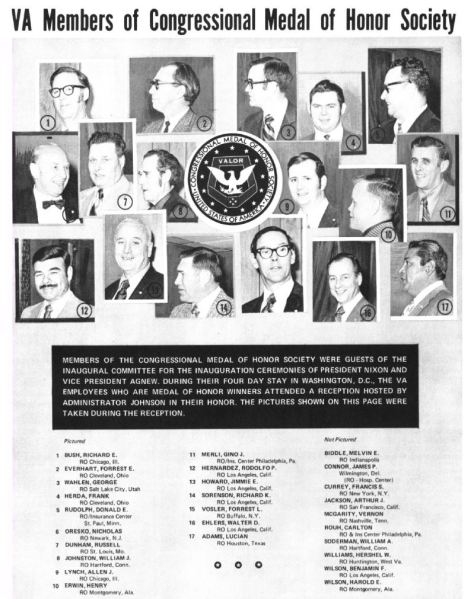

While the agency’s Medal of Honor awardees worked at VA facilities in many different parts of the country, they were able to assemble as a group on occasion. In May 1963, President John F. Kennedy invited all holders of the medal to his annual reception for the military at the White House. Seventeen VA employees made the trip to Washington along with their wives and they met with VA’s deputy administrator at the agency’s D.C. headquarters prior to the event.

Ten years later, an identical number of recipients attended a reception at the headquarters building hosted by VA’s chief administrator during the 1973 presidential inauguration ceremonies. Williams was absent, but the contingent included Bush and another medical corpsman who received his decoration for “conspicuous gallantry” during the grim fighting for Iwo Jima, George E. Wahlen. Notably, Medal of Honor recipients from more recent conflicts were also present. Two Korean War and three Vietnam War Veterans were on hand for the VA gathering that day.

The passage of time took its toll on the Medal of Honor recipients in VA’s ranks and, by the early 1990s, only eleven were still working at the agency. By 2002, the number had dwindled to seven. All had served in Vietnam. Among the last of these stalwarts was Robert L. Howard, who was one of the war’s most decorated soldiers.

He earned his Medal of Honor as a Special Forces sergeant on a mission in enemy-controlled territory to locate a missing soldier in 1968. When his platoon of Green Berets came under heavy attack, he rallied his troops and directed the defense of their perimeter despite being badly wounded himself. Howard joined VA relatively late in life after completing a 36-year career with the Army and retiring as a colonel in 1992. He died in 2009.

Note: Since publication of this entry, we have learned that the plaque does not include the name of Vietnam War Medal of Honor recipient Harold A. Fritz, who worked as a Volunteer Service Specialist in the VA Illiana Health Care System in Illinois.

By Jeffrey Seiken, Ph.D.

Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

American prisoners of war from World War II, Korea, and Vietnam faced starvation, torture, forced labor, and other abuses at the hands of their captors. For those that returned home, their experiences in captivity often had long-lasting impacts on their physical and mental health. Over the decades, the U.S. government sought to address their specific needs through legislation conferring special benefits on former prisoners of war.

In 1978, five years after the United States withdrew the last of its combat troops from South Vietnam, Congress mandated VA carry out a thorough study of the disability and medical needs of former prisoners of war. In consultation with the Secretary of Defense, VA completed the study in 14 months and published its findings in early 1980. Like previous investigations in the 1950s, the study confirmed that former prisoners of war had higher rates of service-connected disabilities.

History of VA in 100 Objects

In the waning days of World War I, French sailors from three visiting allied warships marched through New York in a Liberty Loan Parade. The timing was unfortunate as the second wave of the influenza pandemic was spreading in the U.S. By January, 25 of French sailors died from the virus.

These men were later buried at the Cypress Hills National Cemetery and later a 12-foot granite cross monument, the French Cross, was dedicated in 1920 on Armistice Day. This event later influenced changes to burial laws that opened up availability of allied service members and U.S. citizens who served in foreign armies in the war against Germany and Austrian empires.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Basketball is one of the most popular sports in the nation. However, for paraplegic Veterans after World War II it was impossible with the current equipment and wheelchairs at the time. While VA offered these Veterans a healthy dose of physical and occupational therapy as well as vocational training, patients craved something more. They wanted to return to the sports, like basketball, that they had grown up playing. Their wheelchairs, which were incredibly bulky and commonly weighed over 100 pounds limited play.

However, the revolutionary wheelchair design created in the late 1930s solved that problem. Their chairs featured lightweight aircraft tubing, rear wheels that were easy to propel, and front casters for pivoting. Weighing in at around 45 pounds, the sleek wheelchairs were ideal for sports, especially basketball with its smooth and flat playing surface. The mobility of paraplegic Veterans drastically increased as they mastered the use of the chair, and they soon began to roll themselves into VA hospital gyms to shoot baskets and play pickup games.