The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers officially opened in December 1870 in Hampton, Virginia. Situated on a peninsula formed by the Hampton River and Chesapeake Bay, the branch was the fourth in the National Home system and the first to be located in a former Confederate state. Yet, even as the Hampton site admitted its first residents over the winter of 1870-71, the circumstances surrounding its purchase became the focus of a Congressional investigation. The inquiry centered on the conduct of the president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler, who was suspected of using his public position for personal gain.

Butler was no stranger to controversy. A lawyer and a prominent Massachusetts politician, he secured an appointment as one of President Abraham Lincoln’s “political generals” during the Civil War despite his lack of military qualifications. His record as a military commander was mixed at best. He was vilified by Southerners for his heavy-handed treatment of civilians during the occupation of New Orleans. Butler also acquired a reputation for rapaciousness and was accused of promoting and profiting from the trade of contraband goods across enemy lines. His poor performance during the 1864 campaigns in Virginia and North Carolina prompted Gen. Ulysses S. Grant to remove him from command. Although he retained his commission until November 1865, he did not lead troops in the field again.

Butler returned to politics after the war and was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1866. That same year, he also became the first president and treasurer of the newly established National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. The National Home system provided food, housing, medical care, and community for Union Veterans who could not live independently. In its first two years, the National Home’s Board of Managers under Butler’s direction established branches in Togus, Maine; Dayton, Ohio; and Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

In early 1870, Butler proposed opening a fourth location in Hampton, Virginia. The Southern Branch was intended to benefit African Americans who had served in U.S. Colored Troops regiments during the war, as well as other Veterans whose medical conditions required a more temperate climate. The Board agreed to Butler’s proposal and purchased the Chesapeake Bay lot in July 1870. Formerly home to the Chesapeake Female College, the land included several buildings that could be converted for the National Home’s use.

It was not until after the purchase, however, that the Board learned that Butler was actually the owner of the property. He had initially spent around $12,000 in 1864 to purchase interest in the land, before buying out the remainder of the property in the late 1860s. In total, he spent an estimated $40,000 acquiring the lot. In May 1870, Butler transferred the deed of ownership to his brother-in-law, Fisher A. Hildreth, as collateral for a loan of several thousand dollars. The National Home’s board then purchased the property from Hildreth for $50,000, a notably larger sum than what Butler had paid.

This apparent conflict of interest is what sparked the investigation of Butler by the House Committee on Military Affairs. The committee also questioned Butler over his alleged misuse of National Home funds, much of which were deposited into his personal banking account. The majority of the 1870 Annual Report on the National Home was devoted to the investigation, complete with transcripts of both Butler’s and Hildreth’s questioning by the House committee.

Butler was unrepentant throughout the proceedings. When asked if he ended up pocketing the bulk of the money from the sale of the property, he replied: “O, I did; there is no doubt about that. If this examination was all to get at that fact, I stated it with frankness before.” He refused to admit any impropriety in the acquisition of the Hampton lot or his handling of National Home funds. The committee saw things in a similar light and exonerated Butler of any wrongdoing in the spring of 1871. He retained his position as head of the Board of Managers until 1879.

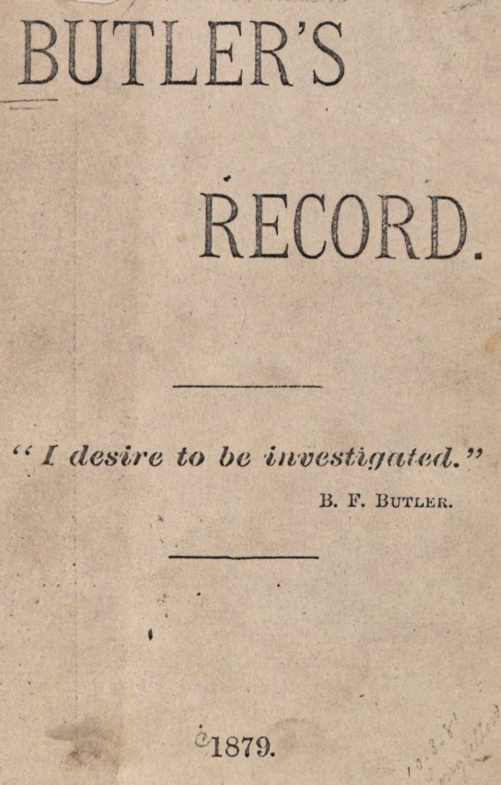

While Butler was cleared by Congress, his political enemies refused to let the issue die. The same year he stepped down from the board, an anonymous author penned a pamphlet titled “Butler’s Record,” that delivered a scathing critique of his actions in public service, including his role in arranging the sale of the property in Hampton. “How,” asked the author, “[could any] credulous soldier or sailor believe in or trust him after this?” A second anonymous pamphleteer sprang to his defense, dismissing the first pamphlet as a “dastardly” attack that omitted key details of the investigation, not the least of which was that Congress found no evidence of misconduct on Butler’s part. The writer also pointed out that the board continued supporting Butler as their president for nearly a decade after the investigation. “Their [e]ndorsement,” he wrote, “is sufficient.”

During his tenure on the board, Butler tried four times to be elected governor of Massachusetts but failed on each occasion. In 1882, his fortunes finally turned and he captured the governor’s office in a narrow vote. However, he lost his bid for a second term, after which he pursued an equally ill-fated presidential campaign. He died in 1893.

The Southern Branch of the National Home welcomed over 300 residents in its first year of operation. Contrary to the Board of Manager’s intent, the Hampton site attracted few African American Veterans. Nonetheless, the board in its 1871 report declared the “experiment” of establishing a branch at Hampton where “colored and white soldiers” could live together “on friendly terms, without compulsion, or without thought of each other except as soldiers disabled in the cause of a common country” to be a complete success. The branch’s population peaked in the late 1890s and early 1900s at around 3,000 Veterans per year. In 1930, the Southern Branch was transferred to the newly established Veterans Administration, and today the grounds are home to the Hampton VA Medical Center.

By Jordan McIntire

Historian, Department of Veterans Affairs

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 93: Occupational Therapy Floor Loom

During World War I and afterwards, the United States committed to rehabilitating sick and wounded soldiers so they could resume productive lives in the civilian workforce. The emerging field of occupational therapy played a crucial role in the rehabilitative process.