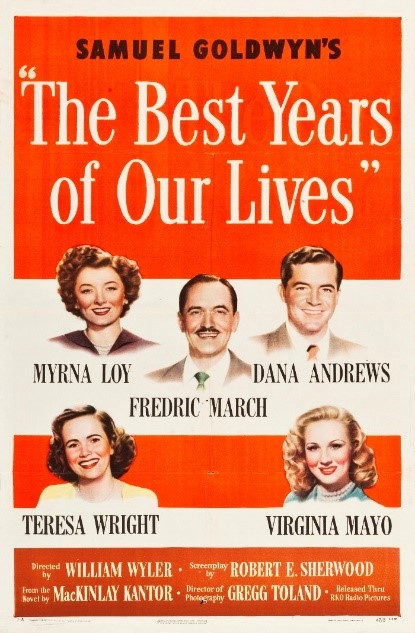

When The Best Years of Our Lives premiered in November 1946, the nation was in transition – and so were millions of World War II Veterans. The war had ended over a year earlier, but the process of demobilizing and discharging 16 million service members was still ongoing. Released just after Veterans Day of 1946 (recognized at that time as Armistice Day), the movie depicted the challenges Veterans faced reintegrating into civilian society – realistically portraying not only the angst and frustrations experienced by returning service members, but those of families and the civilian community as well. The movie was so powerful that General Omar Bradley, then the head of the Veterans Administration, had the movie shown to employees at the central office.1

The story opens with three servicemen (an Army Air Corps bombardier, an Army infantry sergeant, and a Navy petty officer) who meet by chance while traveling to their hometown to be discharged and return to civilian life. The plot follows them through their initial days, weeks, and months of readjustment — touching on controversial issues that movies had previously avoided, including permanent disability, substance abuse, post-traumatic stress, reemployment, changing family roles, and marital frictions.

The Best Years of Our Lives was also groundbreaking in that it disrupts our stereotype of the national mood after World War II. Rather than a universally celebratory tone, the characters are concerned with tensions and post-war unknowns; what the world would be like, now that this global conflict that destroyed dozens of countries and took millions of lives had ended?

It also reflected society at the local level, as communities and families considered the impact of the war experience on the psyche of the men and women returning home. Would they readjust? Would there be jobs for them? What about the permanently disabled? And perhaps most troubling, after the violence and brutality of war, could they return to a peaceful life?

For those familiar with the transition from service member-to-Veteran, the issues addressed in the film remain strikingly authentic. While The Best Years of Our Lives was produced and takes place in 1946, the elements of the military-to-Veteran transition story are timeless. Scholars have reassessed early Greek and Roman literature for depictions of the returning warrior and what we now know as post-traumatic stress disorder. In the U.S., concern about unemployment, alcohol abuse, and the impact of war trauma are recorded since at least the Civil War.2

Adding an additional level of authenticity and impact to The Best Years of our Lives was the common military experience among the cast and crew. It featured multiple Hollywood stars and behind-the-camera specialists who were Veterans, and at least one previously “unknown” Veteran who would win two Oscars for his performance – Harold Russell.

Russell’s portrayal of Homer Parish, the disabled Navy Veteran in the film, was poignantly authentic. An Army Veteran, Russell lost both hands during explosives training during the war and had previously appeared in a Harold Russell, 88; Disabled Actor Won 2 Oscars War Department training film about service member rehabilitation before being cast.3

For his courage in portraying the double-amputee (and putting his own disability on the screen), Russell received a special Oscar for, “Bringing hope and courage to his fellow Veterans through his appearance.”4 Russell accepted the special award, saying, “I’d like to accept this trophy in the name of all those thousands of disabled Veterans who are laying in hospitals all over the country.”5 Later in the ceremony, Russell also received the Best Supporting Actor award, making him the only actor to receive two Academy Awards for the same performance.6

After the movie, Russell continued to champion disabled Veterans and later served as the Chairman of the President’s Committee for Employment of People with Disabilities. In 1992, Russell would sell his Best Supporting Actor statue to raise money for unexpected expenses. Russell died at age 88 in 2002.7

In 1946, when communities were reintegrating 10% of the U.S. population who had served in uniform, The Best Years of Our Lives captured the sometimes-conflicted mood of Veterans and the public at large. The film won eight Academy Awards and went on to be a top box office success, making over $10 million during its initial release, ending the year as the highest grossing film of 1946.8

More importantly, the film brought a story to the public that helped Veterans, families, and communities communicate more openly about the military-to-civilian transition process. In a letter to producer Samuel Goldwyn, General Bradley9 expressed his appreciation for the film, saying, “I cannot thank you too much for bringing this story to the American public.”

More than six decades after the film was released, movie critic Roger Ebert10 still considered its depiction of the Veteran transition realistic when he wrote, “It feels surprisingly modern: lean, direct, honest about issues that Hollywood then studiously avoided. After the war years of patriotism and heroism in the movies, this was a sobering look at the problems veterans faced when they returned home.”

The Best Years of Our Lives can be viewed on multiple platforms today.

The other Veterans of The Best Years of Our Lives

In 1940s Hollywood, military service experience was not uncommon. When the U.S. entered World War II, many industry professionals volunteered, some applying their movie-making skills to produce needed War Department documentaries. Others had served during World War I.

William Wyler

The film was Directed by Wyler, himself a disabled Veteran. One of several top movie directors who volunteered to produce films for the War Department. Wyler served as a filmmaker in the U.S. Army Air Corps from 1942-45, producing two documentaries about the air war in Europe (The Memphis Belle and Thunderbolt!). He personally participated in bombing missions over German-held territory to capture authentic footage for these documentaries, suffering permanent hearing loss in the process. He would win both the Best Picture and Best Director Oscars for The Best Years of Our Lives.

Fredric March

March, a World War I Veteran (a lieutenant in the artillery), played Al Stephenson, an older Veteran, married with two young adult children who have matured while he was away. Stephenson struggles with readjustment and his return to an office job at a bank. Prone to excess alcohol consumption, he adjusts; notably, with the help of his family. During World War II, March toured with the USO, helped in fundraising campaigns, and volunteered at the Stage Door Canteen. He would win the Best Actor Academy Award for playing Al Stephenson and later called it his favorite movie role.

Robert Sherwood

Another Veteran of World War I, Sherwood was the screenwriter for The Best Years of Our Lives. A graduate of Harvard, he had volunteered for service with the Canadian forces prior to America’s entry in the war. He fought with the Black Watch Regiment and was gassed during the war. Sherwood took home the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay.

Gregg Toland

Cinematographer Gregg Toland, already praised for his groundbreaking work on films such as Citizen Kane and The Grapes of Wrath, served as a Navy lieutenant in World War II, working with famed director John Ford. Ford, a member of the Navy Reserve before America’s entry in the war, had organized a Navy Photographic unit. Toland was one of Ford’s first two volunteers. The unit was activated days after the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941 and Toland was immediately ordered to Hawaii to film the aftermath. Much of his documentary, December 7th, was classified and only limited scenes were released to theaters in 1943, winning Toland an Academy Award for Best Documentary Short Subject. Toland was later ordered to Brazil to produce films for the Navy and the Office of Strategic Services before returning to Hollywood in 1945.

Footnotes

- “General Bradley Lauds Film: Praises Best Years of Our Lives in Letter to Samuel Goldwyn,” (New York Times, December 11, 1946), 42. ↩︎

- Matthew Brian Jordan, Marching Home: Union Veterans and Their Unending Civil War (New York: Liveright Publishing, 2014), 43. ↩︎

- Jon Thurber, “Harold Russell, 88; Disabled Actor Won 2 Oscars for ‘The Best Years of Our Lives,” Los Angeles Times, February 1, 2002. ↩︎

- “Academy Awards Acceptance Speech Database: March 13, 1947”, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, “Academy Awards Acceptance Speech Database: March 13, 1947”, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Academy Awards Acceptance Speech. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Jon Thurber “Harold Russell, 88; Disabled Actor Won 2 Oscars for ‘The Best Years of Our Lives’”. ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- “1946 Top Box Office Movies,” Ultimate Movie Ratings, accessed October 28, 2021, 1946 Top Box Office Movies, Ultimate Movie Rankings. ↩︎

- Roger Ebert, “The Home Front Is Also Not Without Casualties,” RogerEbert.Com, December 9, 2007. ↩︎

- “His Camp Worst: Clyde Grimsley Relates Horrors of Hun Prisoners.” The Salina Evening Journal. ↩︎

By Michael Visconage

Chief Historian, Department of Veterans Affairs

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

A Brief History of the Board of Veterans’ Appeals

On July 28, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6230 creating the Board of Veterans’ Appeals (BVA). The BVA was created as part of the Veterans Administration (VA), which had been established only three years earlier.

Featured Stories

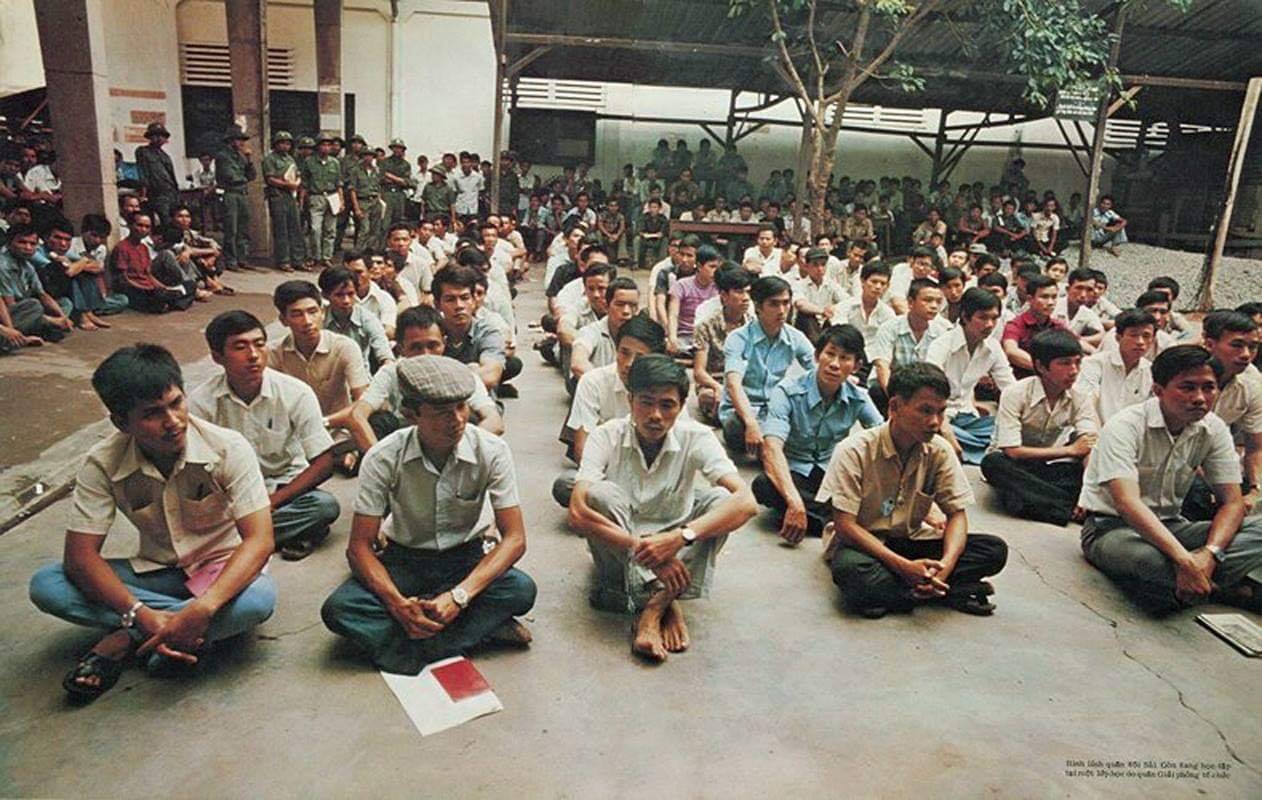

The Fall of Saigon 1975: A South Vietnamese Military Physician Remembers

"There was chaos in the streets when I made my way to the hospital on the morning of April 30, 1975. In a place of order, there was now great confusion. The director and vice director of the hospital were gone, making me, the chief of medicine, the highest-ranking medical officer."