America’s national cemeteries were first authorized on July 17, 1862, as part of a congressional act to fund the Union military forces during the Civil War. Initially, national cemeteries were intended for the burial of those who served with the U.S. (Union) forces.

Most of the first national cemeteries were established in the defeated South and, out of necessity, federal laws were passed to protect the cemeteries and graves of Union soldiers buried there. Many laws in the immediate aftermath of the war rewarded Veterans of the Union forces for their role in defeating what was called, at the time, “the rebellion.”

One example was the first Veterans preference law, enacted on March 3, 1865, which created a federal policy of giving preference to military Veterans when hiring positions for government agencies. As a consequence, the Army’s Quartermaster Department made it their policy to employ Veterans for its growing national cemetery system, which was a winning arrangement for both the department and the Veterans.

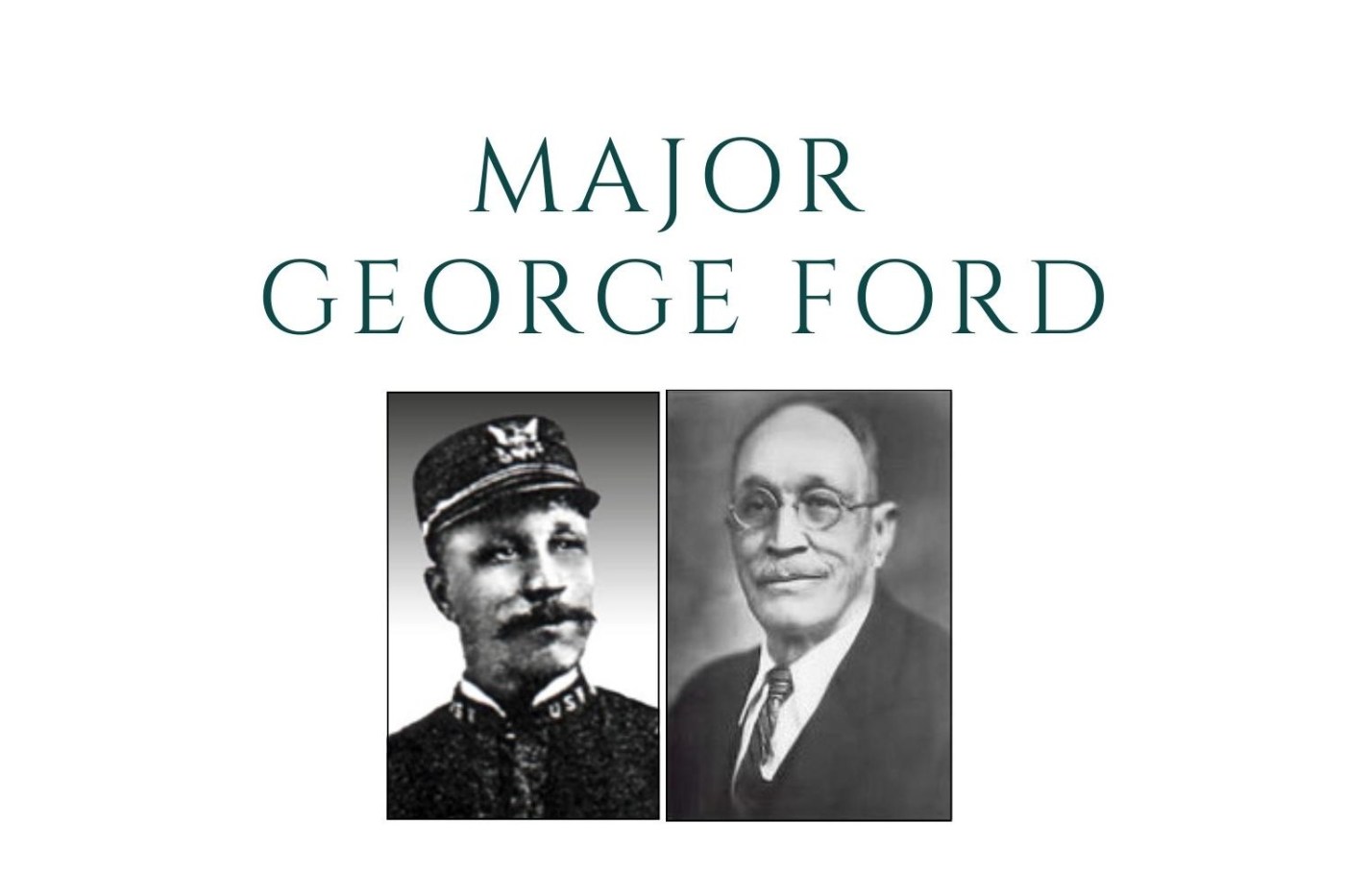

In 1878 Maj. George William Ford, who served as a “Buffalo soldier” after the Civil War, also became one of the first Black Veterans appointed as superintendent of a national cemetery. During an impressive 52-year career he oversaw five national cemeteries in the Midwest and South.

Ford was born on November 23, 1847, near Alexandria, Virginia, and was the grandson of West Ford, an enslaved person belonging to President George Washington’s family. His grandfather obtained his freedom from Bushrod Washington, who inherited Mount Vernon and became a significant landowner in Fairfax County in the nineteenth century.

After the Civil War, the U.S. Army was reorganized. Because of the accomplishments by the U.S. Colored Troops, the Army’s designation for Black troops, the new army included four segregated regiments of Black soldiers. Ford enlisted in one, the 10th Cavalry, in 1867 and served in Kansas, New Mexico, Arizona, and Texas during U.S. wars with various Native American tribes until his honorable discharge in 1873.

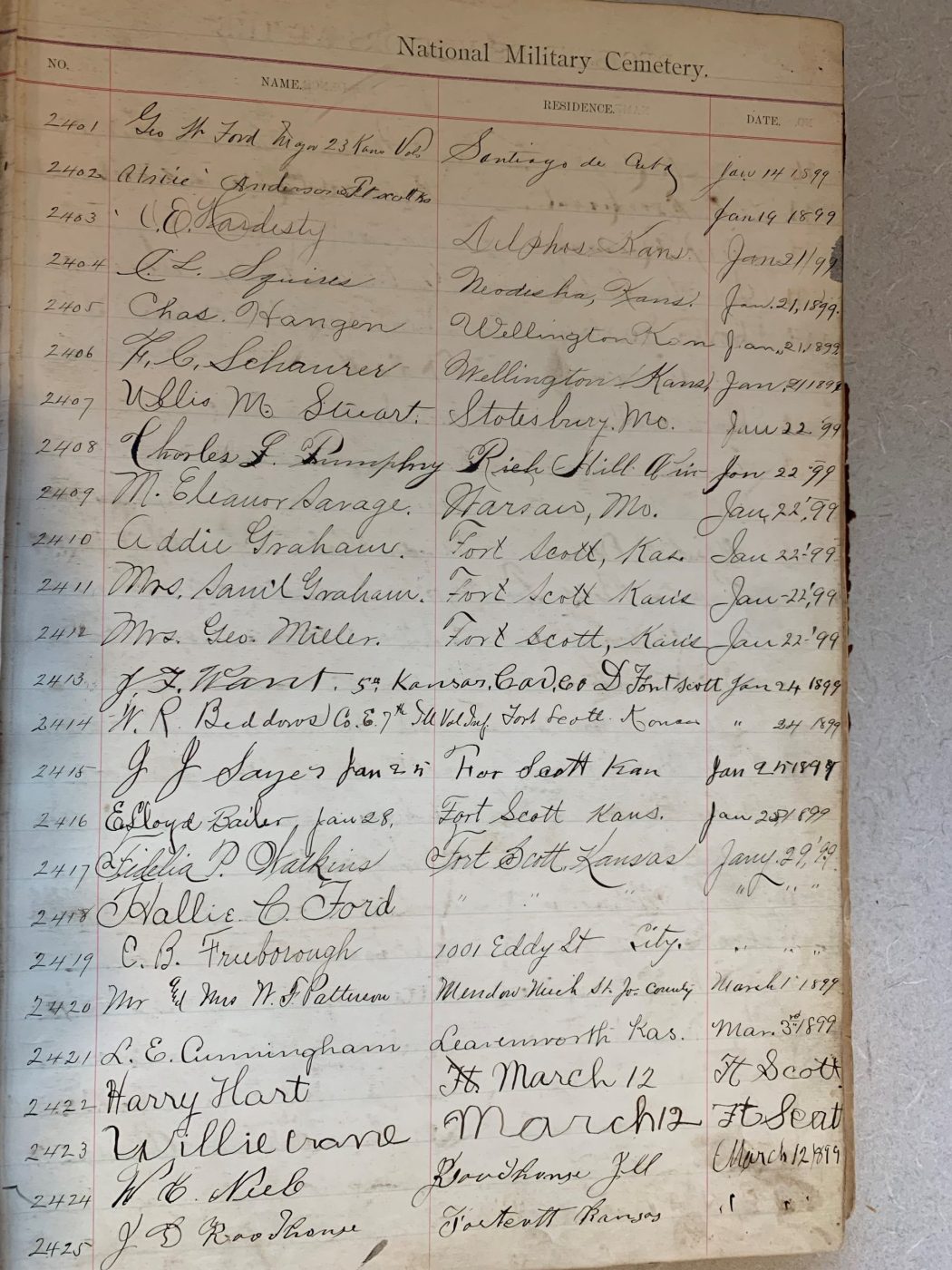

On November 9, 1878, Ford was appointed superintendent at Chattanooga National Cemetery in Tennessee, but was transferred shortly afterward to Beaufort National Cemetery, South Carolina. There he met and married Hattie Bythewood and started a family. He was superintendent at Beaufort for roughly 15 years, until 1894, when he was transferred to Fort Scott National Cemetery, Kansas.

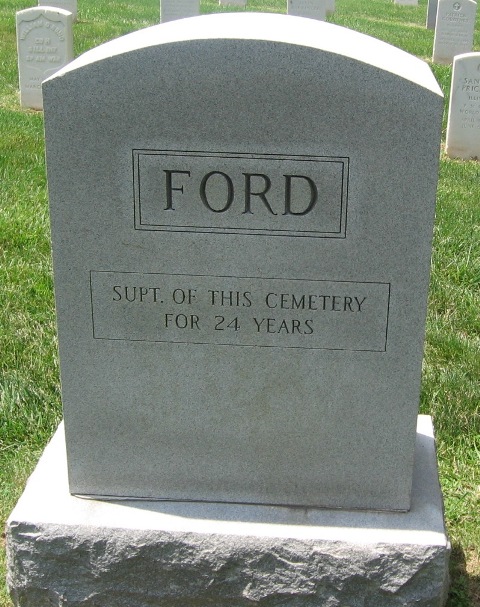

During the Spanish American War Ford took a short leave of absence and served with the Second Battalion of the 23rd Kansas Volunteers. In 1904, he left Fort Scott for Port Hudson National Cemetery in Louisiana. By that time his family had grown to include seven children. Two of his sons went on to graduate from Meharry Medical School and served in World War I. His tenure at Port Hudson National Cemetery was short-lived, only two years, and in 1906 he moved to Camp Butler National Cemetery near Springfield, Illinois. Ford worked at Camp Butler until he retired on October 20, 1930. He died on June 30, 1939 at age 91 and was buried at Camp Butler National Cemetery.

By History Program, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

The Fall of Saigon 1975: A South Vietnamese Military Physician Remembers

"There was chaos in the streets when I made my way to the hospital on the morning of April 30, 1975. In a place of order, there was now great confusion. The director and vice director of the hospital were gone, making me, the chief of medicine, the highest-ranking medical officer."

Featured Stories

History of Former Whipple VA Directors Schmoll And McIntyre

Leadership change is something that happens constantly, whether it’s due to promotion, health, or other circumstances. At the Department of Veterans Affairs’ Northern Arizona Medical Center (formally known as Whipple VA Hospital) in Prescott, Arizona, directors have stayed in their position on average, three to five years. The shortest stint was 22 months, the longest was 16 years and two months. Most former directors moved on and retired elsewhere. However, two former directors, Paul N. Schmoll and Virgil I. McIntyre, either returned to or stayed in Prescott following their retirement. Both men are laid to rest at local cemeteries in the Prescott, Arizona, area.